Over two days in June, the Cryptocurrency Certification Consortium (C4) hosted the inaugural Blockchain Training Conference at MaRS Discovery District in Toronto, Canada. This event saw some of FinTech’s brightest minds come together with entrepreneurs, bankers, regulators, anti-money laundering (AML) professionals and law enforcement officials, to share an array of knowledge and ideas on a single yet revolutionary topic: blockchains.

The prevailing consensus at the conference was that blockchains, and by extension cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, will play an increasingly influential role in the global economy over the next decade. Yet, it was agreed that no one can accurately predict the exact impact that this technology will have on commerce, society and AML.

However, this notion did not stop attendees from hypothesizing on future scenarios where blockchain technology could become the bedrock for many daily undertakings such as renting a car or verifying one’s identity. For example, a senior member of the blockchain community attending the conference predicted that within 10 years, the traditional banking industry as we know it could be reduced to a workforce that is just one third of what it is today due to the efficiencies that can be offered through blockchain’s decentralized and trustless record keeping abilities.

Blockchains and AML

Whether this theory manifests itself into reality will be proven in time, but the challenges blockchain technology currently presents for AML professionals are not predicated in such a revolution; they exist now but are scantly addressed.

Blockchains are the underlying technology that underpins cryptocurrencies. They operate on the principal that a decentralized and widely distributed ledger system can be utilized to record permanent and incorruptible records aided by cryptography and a complex global network of verification points known as nodes.

The combination of cryptography and decentralization allows blockchain technology to fulfill the high expectations attributed to it. For example, maintaining a publicly available and transparent single book of records for various actors without the need for trusted third parties (intermediaries).

Some traditional financial services, (e.g., products associated with trade finance and correspondent banking relationships), could be drastically modified through the use of blockchain technology. Consequently, AML professionals who understand this technology will also be in high demand.

Cryptocurrencies

The remittance of funds between individuals or entities on a decentralized digital ledger, supported by blockchain technology, looks quite different to what is seen on centralized ledgers within the traditional banking system today. This discrepancy alters one’s perception of what may be unusual or suspicious and as a result, a new approach is required by AML professionals to accurately identify and report unusual transactions.

In the traditional system, banks send wires through what can be complicated correspondent banking relationships. For example, in the simplest instance, if underlying customer (Alfred) of Bank A needs to send a wire to underlying customer (David) of Money Exchanger D, this is easily accomplished if Bank A and Bank D have a correspondent banking relationship. Alfred’s Bank A wires funds directly to Money Exchanger Ds account, which are credited to David. Often, correspondent relationships are not that simple and Bank A may have to, for example, route their wire to Bank B, which has a correspondent banking relationship with Credit Union C, whose underlying customer is Money Exchanger D. This example entails fees and duplication of work at every routing instance.

Had blockchain technology been used, Bank A could potentially transfer funds directly to Money Exchange D, without the need of intermediaries. This is because blockchain technology gives two parties that do not know each other the ability to transact, without fear that some fraud has been committed and without the need for intermediaries.

There are several third-party solution providers in the marketplace that offer tools to assist in identifying suspicious or unusual transactions on blockchains such as Bitcoin. Companies like Vancouver-based Blockchain Intelligence Group have already developed sophisticated transaction monitoring alert and case management systems for application in this digital world. However, it is recommended that prior to engaging vendors in the blockchain space, AML professionals should educate themselves on the basics of blockchain technology and on how cryptocurrencies are utilized not only by bad actors, but for legitimate purposes as well.

To help make sense of this and to aid with the advocated self-initiated education, the following outlines two simple but important definitions of transactional environments observed when investigating blockchain-based cryptocurrencies. The two environments are labeled as the interactive environment and the contained environment.

Interactive Environment

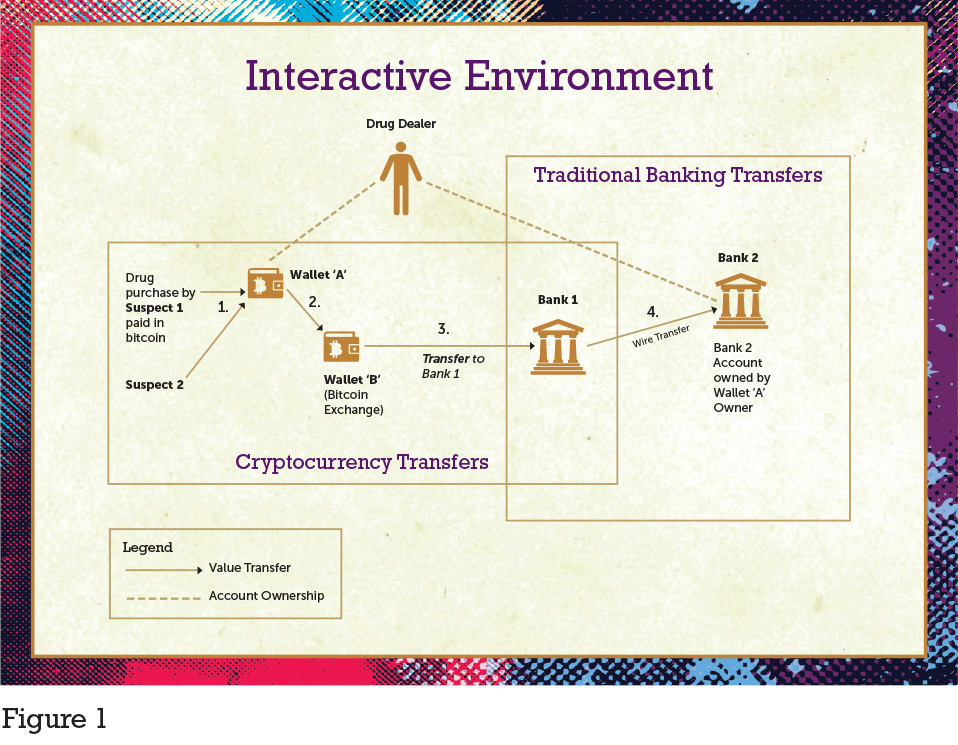

The interactive environment is one where cryptocurrency activities intersect with the traditional banking system. Figure 1 highlights the interaction between the traditional banking system and the cryptocurrency blockchain. In particular, it is an example of how a blockchain can serve to obscure the flow of funds related to illicit transfers of wealth.

This scenario involves a drug trafficker who utilizes Bitcoin wallets, Bitcoin exchanges and wire payments to layer the proceeds of crime. The trafficker sells drugs and is paid in bitcoin; the bitcoins are then layered through two Bitcoin wallets before the value is converted to fiat currency at a Bitcoin exchange and then further layered by wires through the traditional banking system.

An AML investigator at Bank 1 would observe the wire payment coming in from the Bitcoin exchange, but not necessarily be aware that the remitter was a Bitcoin exchange. It is for this reason that AML professionals working in financial institutions should become aware of the various cryptocurrency exchanges, and which are large, established and better trusted.

At Bank 2, AML investigators would not have sight of the nexus to Bitcoin and would merely see a bank to bank wire transfer; the investigator would be unable to make the link that their customer also owns Wallet ‘A.’ Such predicaments suggest cryptocurrency exchanges should also have efficient know your customer, enhanced due diligence (EDD) and AML regimes.

Contained Environment

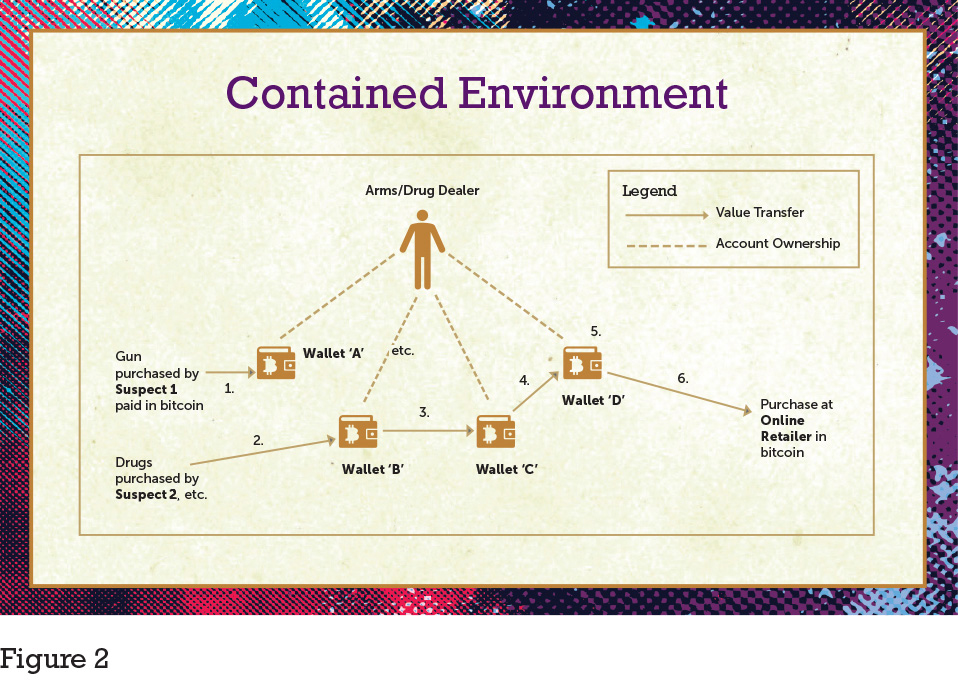

In a contained environment all transactions occur outside the traditional banking system and are only visible within a given blockchain.

In Figure 2, the arms/drug dealer is able to collect money (transaction 1 and 2) and layer the proceeds of his drug sales (transactions 3 and 4) entirely on the blockchain. In transaction 5, the drug dealer purchases a luxury good through an online retailer using bitcoin. It is unlikely that an AML analyst in a financial institution would be privy to any of these transactions.

While it might be suggested that blockchains are a gift horse for law enforcement as everything (transactionally) is visible and publicly available, such overly simplified statements face many limitations caused by the lack of knowledge of blockchains and techniques used to obfuscate the sources of funds.

AML Challenges Associated with Cryptocurrencies

Like accounts in the traditional banking system, blockchain wallets are susceptible to limitations around record keeping and the identification of account owners and beneficial owners. In both cases, a person could, for example, use synthetic identities or proxies to open accounts. A synthetic identity is an identity that does not exist in real life. In other words, the person was never born and this differs from stealing the identity of a real person (ID theft).

By virtue of its existence in the digital environment, transactions on the blockchain are also made more difficult to follow with IP address anonymizers as well as mixers and/or tumblers. While IP anonymizers help to obfuscate the real location of a wallet owner, mixers and tumblers help to conceal the origin of funds.

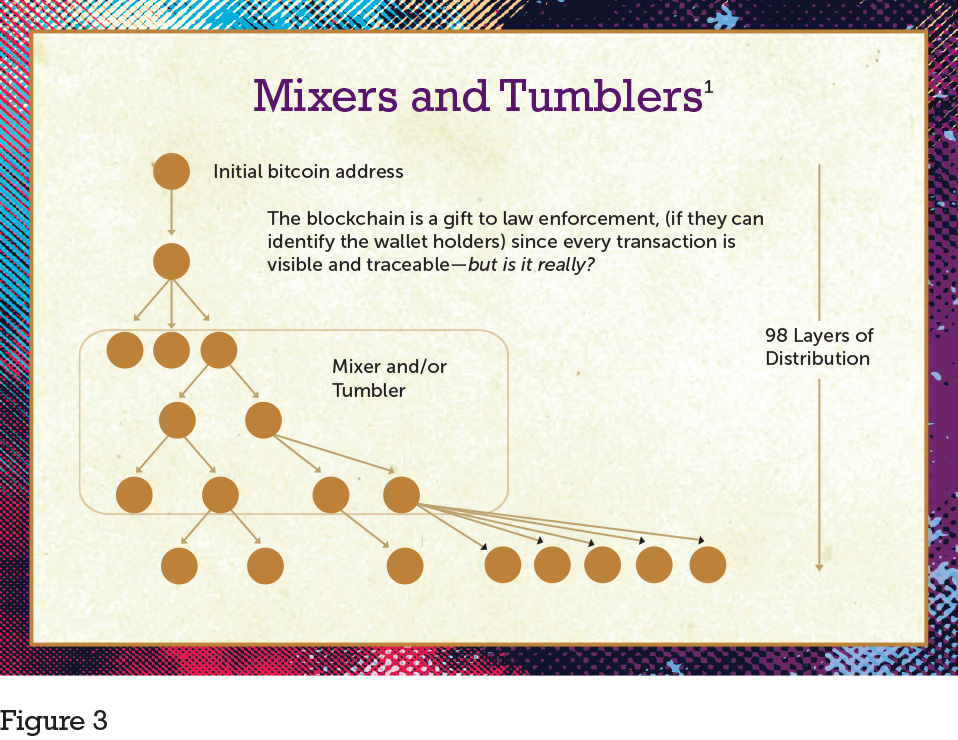

Figure 3 details a real scenario where researchers in Russia attempted to identify suspicious transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain. In this example, one bitcoin transfer is subdivided through 98 transactional layers and paid to other Bitcoin wallet holders.

The rectangular box overlaid on the middle subset of these transactions represents the injection of mixers and tumblers into the equation. Mixers and tumblers are freely available services offered by companies online. Some of these companies openly offer to launder subscribers’ bitcoins to obscure or at the very least, make the transactional trail and sequence of events more difficult to follow. Not surprisingly, the use of a mixer/tumbler is in and of itself a money laundering/terrorist financing red flag.

Mixers combine bitcoins with the bitcoins of others. Users send bitcoins to a central address. The mixer sends a transaction back to each user from the key controlling the central address. When stolen bitcoins (or bitcoins used to launder funds) mix with ‘clean’ bitcoins, they become difficult to track.

Tumblers swap bitcoins between users. A tumbler mixes bitcoins and sends transactions with various amounts to keys it controls, in an attempt to simulate other network transactions. For example, a user who sends a tumbler one bitcoin may receive multiple, smaller, transactions in return over a short time. The bitcoins returned to the user will have been combined, split and transacted many, many times.

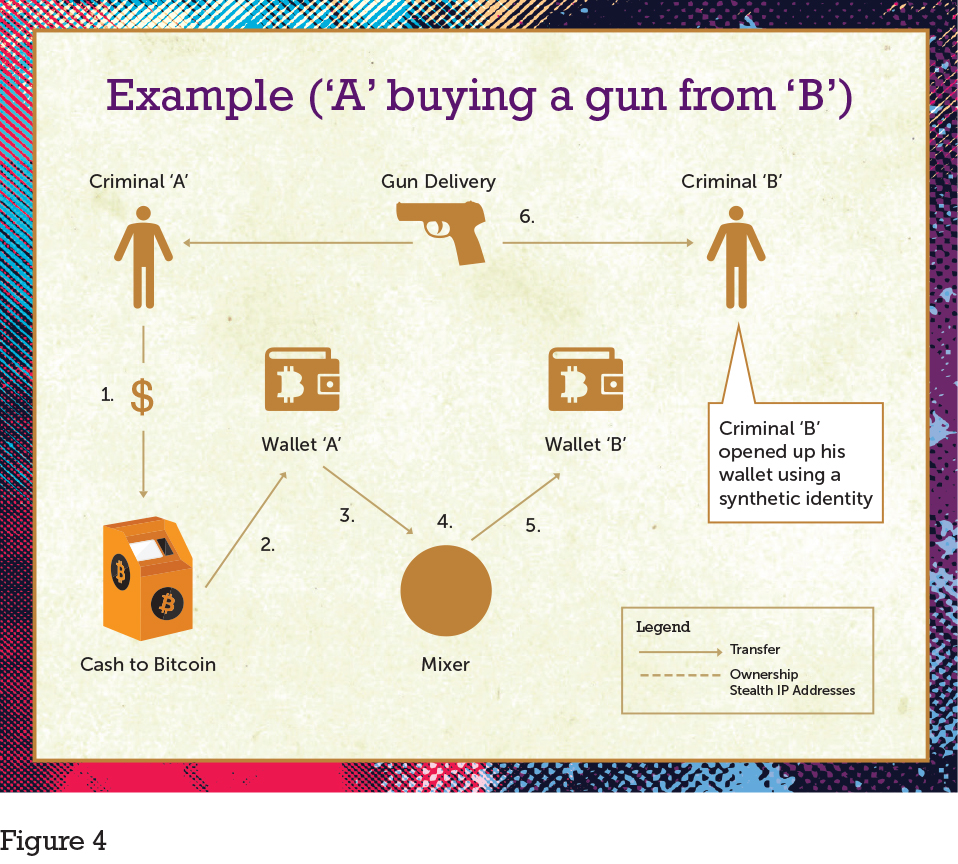

When synthetic identities are utilized with mixers and tumblers and cash converted to bitcoins via cryptocurrency ATMs (which may lack customer due diligence/enhanced due diligence [CDD/EDD] standards), and online transactions are conducted from stealth or anonymized addresses and the parties operate in multiple jurisdictions, the challenges facing law enforcement and AML professionals are not difficult to follow as shown in Figure 4.

In Figure 4, Criminal A converts cash into bitcoins using a Bitcoin ATM and deposits the bitcoins into Wallet A. The funds from Wallet A are ‘mixed’ and sent to Wallet B, owned by Criminal B. Upon receiving the payment in bitcoins, Criminal B hand delivers a weapon to Criminal A. Organized criminal networks and terrorists can conduct nefarious deals outside of the regulated financial system using such methods.

Conclusion

Blockchain technology is here to stay as the potential it presents—including trustless record keeping—offers far too many possibilities to abandon. However, how this technology ultimately interacts with traditional financial institutions and society as a whole is yet to be seen. What is determinable at this time is the effect of blockchain technology’s first tangible use case, cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, has on AML professionals worldwide.

Cryptocurrencies open a new dimension in transaction monitoring and AML processes as a whole. This new dimension is comprised of competing environments (interactive and contained) and requires different approaches to accurately identify suspicious transactions when investigating each.

As AML and law enforcement professionals what is clear is the need for knowledge and education in this space, not just to make sense of this new technology, but to compete in a world of AML that may see drastic change. The BlockChain, Cryptocurrency and AML Conference in Toronto on August 25, 2016, is a prime example of how important this technology is to the AML field. This is the future of AML and it is important for AML and law enforcement professionals to keep up-to-date. Attendees included law enforcement, FINTRAC, government policymakers, major banks, blockchain and cryptocurrency professionals, the Blockchain Alliance and ACAMS members.

Many financial institutions have created blockchain centres of excellence that aim to study and test possible blockchain-based tools and products. These innovations must come hand in hand with deep research into the related AML implications.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not in any way be construed as reflective of the opinions, policies, or procedures of the Bank of Montreal or its subsidiaries.

- Diana Mergenovna Sat, “Investigation of Money Laundering Methods through Cryptocurrency,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, January 20, 2016, http://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol83No2/11Vol83No2.pdf

Great article!, thank you!.

The future is here now