If you have either prepared or read a current Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) in the United States, the chances are high that it will involve the structuring of currency transactions. Some bank customers creatively contrive to deposit or withdraw currency to avoid the $10,000 Currency Transaction Report threshold. Approximately one third of all SARs filed in the United States relate to some type of suspicious activity with currency transactions. It is understandable that many of those personnel involved with preparing these SARs wonder how reporting such repetitive, mundane and seemingly trivial activities could actually help law enforcement. Similar thoughts must have crossed the mind of bankers during the 1930's as they assisted law enforcement with the infamous Lindbergh baby kidnapping. The following story illustrates how one banker's compliance with the reporting of a single transaction made a difference, just as one SAR can make a difference in exposing seemingly unrelated criminal activity.

Charles Lindbergh amazed the world in 1927 when he became the first man to fly solo across the Atlantic. Lindbergh was a worldwide hero and hailed as the pinnacle of America's can-do spirit. Fame, fortune and a family soon followed. Americans relished the news of Lindbergh's marriage to Anne Morrow, a wealthy socialite, and of the birth of their first born son, Charles Lindbergh, Jr., nicknamed "Little Lindy." Americans were shocked and horrified when Little Lindy was kidnapped on March 1, 1932. The infant was taken from his home in the middle of the night from the Lindbergh's rural residence in New Jersey. The kidnapping and the sensational findings during the subsequent investigation were front page news across the nation. However, the less public details of how the bankers and law enforcement officers worked together to solve this crime is often overlooked. Recently author Lloyd Gardner published a very well researched book on this subject.1 This article incorporates significant facts from Gardner's publication and from rarely seen Internal Revenue Service (IRS) archives.

The morning after the kidnapping of Little Lindy, local law enforcement investigators examined the ransom note and the abandoned make-shift ladder used to reach his second floor bedroom. The ransom note was handwritten. Yet, given the gravity of the situation and brevity of the note, it was odd that it transcribed poorly, contained grammatical mistakes and strangely misspelled words. Regrettably, the ransom note, the ladder, the kidnappers' footprints, as well as any other evidence which could have provided leads for the investigation were unwittingly corrupted by the Lindbergh family, their domestic staff, first responders, and members of the press. Closer examination of the ransom note revealed the kidnappers had purposely added cryptic circles, colors, and holes on the face of the note as a type of authentication for future contacts. In the following weeks, the kidnappers delivered numerous notes to Lindbergh utilizing these same cryptic circles with equally poor penmanship and composition skills.

As newspaper reporters were relaying details of the kidnapping investigation to the public, one of the most interesting offers to assist with locating Little Lindy came from the former Public Enemy #1, Al Capone.2 At the time of the abduction, which happened prior to Capone's transfer to Alcatraz, he was serving time in a Chicago prison. Capone offered to pay the ransom on behalf of Lindbergh and he hinted the kidnapper was an unnamed fellow gangster from New York. Capone proffered his assistance, with the condition that he be released from prison and pardoned for his tax crimes.

This audacious offer sparked Lindbergh to contact an influential and personal friend, Odgen Mills, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. Mills enlisted the services of the IRS Intelligence Unit, the forerunner to the current IRS-Criminal Investigation. Elmer Irey, the Unit's leader, directed Special Agent Frank Wilson to investigate Capone's "offer." Frank Wilson, who was instrumental in landing Capone behind bars for income tax violations, employed the use of a jailhouse informant and quickly discovered Capone's offer was nothing more than a trick by Capone to negotiate a release from prison. Nonetheless, Lindbergh was impressed with how the IRS tracked the Capone lead. Lindbergh requested Irey and Wilson assist with the negotiations for the return of Little Lindy.

Irey and Wilson became a crucial part of an ad hoc advisory team which, in part, involved the delivery of ransom to the kidnappers. The savvy kidnappers demanded Lindbergh pay the ransom with small denomination non-sequential serial numbered bills. The IRS agents in turn devised a counter plan. The IRS was aware the Treasury Department planned to discontinue circulation of the gold certificate currency within the next year. However, this information was not public knowledge and certainly not known to the kidnappers.

For the plan to work, the IRS team laboriously recorded a master list of each and every serial number of the gold certificate bills intended for the $50,000 ransom payment. As smaller denominations of gold certificates bills, such as $5s, $10s and $20s, were to be used in the ransom, this list expanded to over 5,100 random serial numbers. The batches of currency were wrapped with a unique string and paper that could be readily identified if ever seen again. Lindbergh entrusted John Condon to deliver the $50,000 ransom to the kidnappers on April 2, 1932. However, Little Lindy was not returned to Lindbergh as the kidnappers had promised.

Approximately one month later, on May 12th, the decomposing body of Little Lindy was found in the dense woods within short distance from Lindbergh's home. Sadly, it was later determined the cause of death for the baby was a fatal strike to the head that probably occurred during the night of the kidnapping.

After the discovery of the missing child, the IRS quickly distributed copies of the list of ransom payment serial numbers to banks throughout the New York City region and beyond. Unfortunately, the press received a copy of this same list and immediately published it. This news logically chilled the kidnapper's initial use of these bills. However, the bills did occasionally surface starting seven months after the ransom was paid and bankers routinely alerted law enforcement accordingly.

Just imagine, for the bank tellers and back officer personnel to spot the identified currency they examined thousands of customer deposits, then it was necessary to compare each suspect bill to the list of over 5,100 serial numbers. Finding a match was laborious and seemed unlikely.

Approximately one year later, on April 5, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order which required Americans to redeem and replace all gold certificate currency on or before May 1, 1933. During this month, the kidnappers succeeded in converting nearly $15,000 of the ransom. Based upon the extraordinary volume of currency conversions in such a short period of time, it was understandable the bankers could not recall who converted which bills.

Regardless, from 1932 through 1934 the local police, the FBI, and IRS Special Agents traced the reported ransom bills. They all hoped for some sort of lead back to the kidnappers. Incredibly, New York City Police Lieutenant James Finn championed the effort, following nearly 600 leads generated from a total of 716 bills. As a side note, Lieutenant Finn previously served as Lindbergh's personal bodyguard upon his hero's return to the United States in 1927.

Lieutenant Finn's devotion to Lindbergh became legendary, as he maintained a city map marked with pins which noted the location of discovery and denomination of each ransom bill the bankers found. While Finn knew most of the bills had been transacted in and around New York City, there was no definitive pattern to anticipate where the next bill would pop up. It was intriguing though not helpful to learn that the most recently discovered bills were transacted in the order they were listed on the serial number sheet.

Over two years later, on September 18, 1934, a banker's diligence paid off. The Branch Manager for the Corn Exchange Bank discovered a deposit of a $10 Gold Certificate matching the serial number list. For this bank, examining this $10 bill may have been similar to reviewing the hundreds of bills discovered before this one came along. This bill became the key evidence that unlocked the case of the century. To the banker who found this key evidence, it must have appeared to be another boring and unnecessary task at the time he found it. Maybe he felt as many of you do today, another SAR about structuring that will go nowhere.

Nevertheless, this banker immediately alerted the authorities. Finn, just as he had always done, carefully inspected the bill for clues. His eyes must have nearly popped out when he noticed '4U-13-41' handwritten on the back of the bill. He immediately recognized the significance of the numbers and dashes; it was a license plate number for a vehicle registered in the State of New York.

Finn knew he needed to locate the merchant who made the deposit. Finn wisely considered interviewing the three gasoline stations that made deposits with Corn Exchange Bank during the prior week. The Quinlan Oil Company was Finn's first stop. The gas station manager, Walter Lyle, recalled an immigrant from Europe purchased $1 of gasoline with this $10 gold certificate. Lyle knew that the possession of gold certificates was unusual following President's Executive Order. Lyle said, "You don't see many of these anymore." The customer replied, "Ah, yes, you do. I've got a hundred of them left at home."3 Lyle suspected the bill was a counterfeit and just in case it was, he jotted down the customer's license plate number.

Finn recalled that Condon, the person entrusted by Lindbergh to deliverer the ransom money, thought the kidnapper spoke with a German accent. That was a lead in the right direction but Finn needed more. Finn immediately tracked down the license plate application and compared that handwriting to copies of the ransom notes. The handwriting was nearly a match to a German immigrant, a Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Hauptmann's residence was immediately placed under surveillance. The following morning, Hauptmann was arrested by a team of law enforcement officers, which included the local police, an FBI agent and of course Finn. Hauptmann's landlord mentioned that Hauptmann was a carpenter, who requested permission to build a detached garage at his residence three years earlier. The search of Hauptmann's garage was particularly revealing since hidden into numerous and creative spots throughout the structure was $13,760 of the ransom money.

David Wilentz, the Attorney General of New Jersey, took responsibility for the high profile prosecution of Hauptmann. The prosecutors had several things going for them: Hauptmann had a weak alibi for his whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping; Hauptmann's handwriting "matched" that shown on the ransom notes; wood from the make-shift ladder found at Lindbergh's house was a "match" to part of the lumber Hauptmann used to build his garage; John Condon's name and number were written on a closet wall in his house; and of course law enforcement discovered a significant amount of the ransom money in his garage.

While this was certainly strong evidence, Wilentz was aware of the potential weakness within this case. Hauptmann gave a somewhat plausible and consistent story, and there were no reliable eye witnesses putting him near the kidnapping site. Hauptmann claimed he 'appropriated' the ransom money from his recently deceased business partner. As it is necessary today with high profile crimes and complex financial cases, it was necessary then for the prosecutor to follow the money to prove the underlying crime. Wilentz specifically requested financial investigative experts from the IRS to be a part of the prosecution team.

The IRS Special Agents heartily delved into this task. However, to accomplish their analysis for the prosecutor, accelerated cooperation from the bankers was necessary. The Agents knew about the stash of ransom money found in his garage and uncovered an additional $5,500 cash investment, but what about the rest? The bankers produced evidence of deposits and transactions from Hauptmann's bank and brokerage accounts totaling $29,766. The financial records corroborated the timing of the kidnapping to the date Hauptmann quit his job, as well as the timing to when Hauptmann's wife quit her job just a few months later. Archives of the IRS investigation revealed that Hauptmann spent or invested $49,986 more than his legitimate earnings or savings within a 28 month period of the ransom payment.

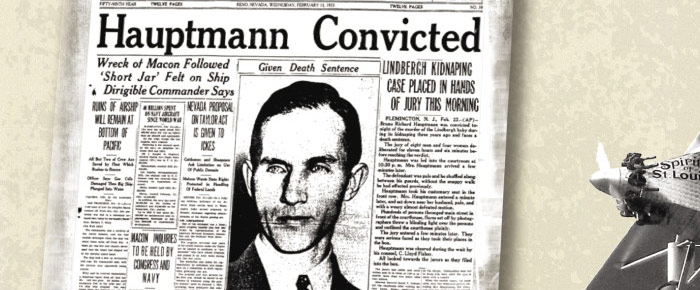

Hauptmann's criminal trial began on January 3, 1935, less than four months following his arrest. During the trial, the IRS Special Agent in Charge described the foundation of the investigation that led to the capture of Hauptmann which included the list of serial numbers used for the ransom money. The court heard testimony by another IRS Special Agent who described how he tracked nearly all of the ransom money, with his analysis of bank deposits, withdrawals, and transfers. The financial evidence added unequivocal evidence of Hauptmann's participation with the Lindbergh kidnapping. A jury found Hauptmann guilty of murder in the first degree and he was executed just over a year later.

In a nod to the investigative skills of the IRS Special Agents involved in the case, Lindbergh told Irey at the conclusion of the trial, "If it had not been for your fellows being in the case, Hauptmann would not now be on trial and your organization deserves full credit for his apprehension."

In retrospect, this case is an example of the same cooperation that exists today between bankers, money service businesses, and other members of the public with matters of sensitivity or national security. The ability to track nearly every dollar of the ransom money is an example of extraordinary investigative diligence by law enforcement with essential assistance from the banking community. For the IRS agents and bankers to account for and trace such a significant amount of financial data within this short period of time is amazing, as the value of $50,000 in 1932 is equivalent to $830,000 today.

While it was certainly a bold idea for the IRS to distribute the list of serial numbers of the gold certificates used for the ransom, the second part of the plan could only work with the conscientious cooperation from the banking community. Two years following the ransom payment, the branch manager from the Corn Exchange dutifully compared the $10 bill to the list. This banker could have easily considered the process of checking the serial numbers not worth his time or irrelevant. Credit must be given to all the bankers who compared literally thousands of innocuous gold certificates to the IRS list in order to find the relatively few hundred gems.

In comparison to the 1930s, the banks and law enforcement community have come a long way. While a manual search for serial numbers on individual bills is not currently practical, tracking and reporting suspect customer transactions through banking systems is an everyday activity. If a bank were to discover a hot lead, a Suspicious Activity Report would be the mechanism to alert law enforcement and provide safe harbor for related privacy issues.

While it may not seem to be anything more to the financial sector than another currency report, who knows, your seemingly mundane SAR may be the next $10 bill that can initiate a major investigation or provide key assistance with an ongoing investigation.

- The Case That Never Dies &mdash The Lindbergh Kidnapping by Lloyd Gardner (2004).

- The Tax Dodgers by Elmer Irey.

- Time Magazine. National Affairs: 4U-13-41. Published on October 1, 1934.