While anti-money laundering (AML) professionals focused on finding and reporting pandemic-related fraud and adjusting to a virtual world in 2020, 2021 brought a sense of calm. Emphasis by governments and regulators on risk-based anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing (AML/CTF) programs, building solid frameworks for sanctions programs and partnering with law enforcement are all old standards that every AML professional can support. New legislation, proposed regulations and guidance from regulators in 2021 have provided clear direction in the fight against money laundering and sanctions violations.

U.S. Regulatory Updates

AMLA

2021 kicked off with a bang when the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA), part of the National Defense Authorization Act, was signed into law on January 1. Passage of this modernizing legislation came at an inflection point in the AML/CTF industry following years of regulatory actions, fines, leaks and more. The AMLA created a significant opportunity to strengthen the public and private AML/CTF regime, including improved communication and information sharing with law enforcement, establishing a national beneficial ownership registry and building risk-based AML/CTF programs that are effective.

One of the most widely anticipated actions of the year is the publication of the national priorities by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) as mandated by the AMLA. On June 30, FinCEN met its deadline by issuing a statement1 in which eight national priorities were identified. The issuance of national priorities was anticlimactic, as the list is so broad it is difficult to imagine any money laundering-related topic that does not fit into one of the categories. The publication of the priorities does not create new regulatory requirements; instead, financial institutions (FIs) have to wait for implementing regulations to discover how FinCEN expects the priorities to be worked into risk-based AML programs. Table 1 covers such examples from 2021.

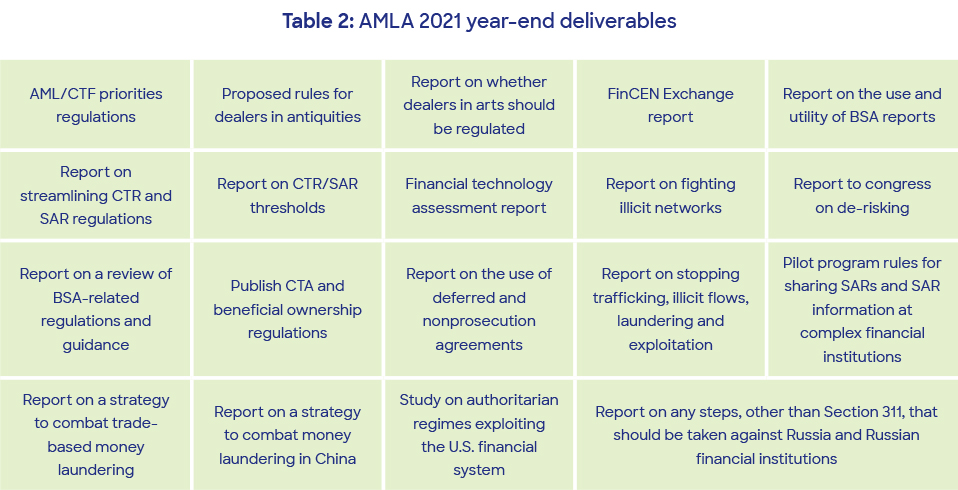

Many of the deadlines created by the AMLA are in late 2021 or beyond, so the impact of the requirements will not begin to be felt until 2022 (see Table 2).

Suspicious Activity Reporting

On January 22, the four U.S. regulators published a proposed rule to revise suspicious activity report (SAR) regulations, which would permit them to provide a temporary exemption from SAR requirements. Only the FinCEN currently has this ability. This is a proactive measure allowing FIs some relief while developing innovative solutions to meet the Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money laundering (BSA/AML) requirements more efficiently and effectively.

Examination Guidelines

The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) updated the following sections of the BSA/AML Examination Manual:

- “Introduction—Assessing compliance with Bank Secrecy Act Regulatory Requirements

- Customer Identification Program

- Currency Transaction Reporting

- Transactions of Exempt Persons”2

These updates were intended to provide further transparency on the examination process and support risk-focused examinations. They did not create new regulatory requirements.

Model Risk Management

U.S. regulators also provided guidance on models, including building in latitude for FIs to rethink whether automated transaction monitoring (TM) systems are models as newly interpreted. Until now, the primary guidance being used for model risk management was issued by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) in April 2011 for financial models.3 It took 10 years for the regulators, through an interagency statement,4 to acknowledge what many AML/CTF professionals already knew—not every automated TM system/process is a model as defined in the 2011 OCC guidance. The April 2021 guidance was clear that FIs can use discretion in defining what constitutes an AML/CTF model:

“While some BSA/AML systems may constitute models under this description, others may not. The determination by a bank of whether a BSA/AML system is considered a model is bank specific, and a conclusion regarding the system’s categorization should be based on a consideration of all relevant information. There are no required categorizations of particular BSA/AML systems, including those used to monitor for suspicious activity.”5

The focus on models continued when the FFIEC issued a request for information on the extent to which supervisory guidance on model risk management supports compliance with BSA/AML and the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) requirements.

International Regulatory Updates

Joint Regulatory Forum

The U.S. and European Union (EU) issued a joint statement on U.S.-EU Joint Financial Regulatory Forum on March 29, 2021.6 The forum focused on six themes, one of which was AML/CTF issues, including pandemic-related fraud and money laundering, the AMLA and EU AML Action Plan implementation. In the spirit of collaboration, participants recognized the potential for enhanced cooperation to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

Criminal Law Directive

The EU implemented the Criminal Law Directive (frequently referred to in the industry as the Sixth AML Directive), which made money laundering offense definitions consistent throughout EU member states, introduced 22 predicate offenses, subjected legal persons (e.g., companies and partnerships) to criminal liability, brought tougher money laundering offense punishments and enhanced prosecution cooperation between EU member states.

FATF

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has acknowledged major strides in the U.S., specifically in the area of customer due diligence (CDD), which is largely due to the CDD Final Rule in 2018. However, FATF did note some areas for improvement in U.S. AML/CTF processes.7 The recent pace of published guidances, advisories and regulatory changes from the U.S. government and regulators rivals its EU counterparts.

Pandora Papers

Another year, another report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) on how the rich and famous use trusts and shell companies established in tax havens to avoid and/or evade taxes. On October 3, ICIJ released the Pandora Papers8 brought about through the leak of millions of documents. The investigation uncovered financial secrets of 35 current and former world leaders, more than 330 politicians and public officials in 91 countries and territories, famous people and a global lineup of fugitives, con artists and murderers. In addition, 14 companies were identified as primarily responsible for establishing the framework that permits the named parties to avoid/evade taxes.

Also covered in the papers are a few U.S. states that encourage the incorporation of anonymous trusts and shell companies, bringing fast and easy revenue to the states. Of the 206 U.S.-based trusts identified in the Pandora Papers, 81 are based in South Dakota. In addition to secrecy protections afforded by South Dakota trust laws, other benefits to using a U.S. state as a tax haven include the stable U.S. dollar and solid infrastructure. Other states known for friendly tax haven policies are Nevada, Wyoming, Alaska, Florida, Texas and Delaware.

The ICIJ gave clear indication that the named parties are (illegally) evading taxes but are careful not to express the assumption in any of its writings surrounding the Pandora Papers.

Exactly what the release of the Pandora Papers means to FIs remains to be seen. It is doubtful that FIs did not know that the 35 named parties are politically exposed and/or wealthy. Highlighting the use of offshore trusts is not likely to bring about a de-risking of the wealthy and politically connected.

ENABLERS Act

The publication of the Pandora Papers prompted another attempt to bring enablers/gatekeepers into the BSA/AML regime. U.S. lawmakers proposed the ENABLERS Act,9 which would do the following:

- Require trust companies, lawyers, art dealers and others to investigate foreign clients seeking to move money and assets into the American financial system10

- Eliminate the temporary AML program exemption for real estate professionals, sellers of luxury cars, ships and aircraft

- Make the real estate geographic targeting order applicable nationwide and include commercial property sales

- Require that the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA)11 include a strategy for gatekeepers

Passage of the ENABLERS Act would be a huge step toward closing what many see as a large BSA/AML regulatory gap. If passed—and that is a big if, given the extensive lobbying efforts over the years against such actions—all covered enablers/gatekeepers must be in compliance by June 30, 2024.

Technology

Pandemic Fraud

Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act frauds included Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan and unemployment insurance fraud. Fraudsters have been busy scheming and conniving ways to obtain billions of dollars of taxpayer-funded aid. For PPP loans alone, “Around 1.8 million of the program’s 11.8 million loans—more than 15%—totaling $76 billion had at least one indication of potential fraud.”12 Glimpsing the Justice Department website13 on frauds related to the CARES Act evidences the few—relative to the overall estimate of fraud cases—CARES Act fraud cases made public. The government seems intent on finding CARES Act fraudsters and prosecuting them.

Examining the role of fintech firms in the pervasive PPP loan fraud also yields staggering information.14 That fraud exists in the PPP loan program is no longer a secret, and that fintechs initiated a large part of the fraudulent loans is undeniable. While the 80/2015 rule certainly seems to correlate to fintechs and PPP loan fraud, the U.S. government has apparently not received that message. FinCEN has issued almost a dozen bulletins16 geared toward FIs, including four new ones in 2021. The mortgage industry has had to address at least 50 updates, the education system three alerts and businesses around 50 updates.17 None of these were specifically geared toward fintechs. Finally, of the top three offenders for originating fraudulent loans, the government has thus far been silent regarding fines or penalties.

Ransomware

With ransomware payments in the hundreds of millions of dollars,18 OFAC and FinCEN delivered a strong message in 2021—through advisories and OFAC’s designation of SUEX OTC, S.R.O. (a virtual currency exchange)—that paying ransom to blocked persons is a violation and will be treated as such.

In October 2020,19 OFAC updated its September 202020 ransomware advisory and emphasized the following:

“…the U.S. government continues to strongly discourage the payment of cyber ransom or extortion demands and recognizes the importance of cyber hygiene in preventing or mitigating such attacks. OFAC has…emphasize(d) the importance of improving cybersecurity practices and reporting to, and cooperating with, appropriate U.S. government agencies…. Such reporting…is essential…to understand and counter ransomware attacks and malicious cyber actors.”21

In October, FinCEN quickly followed with its first AMLA-required semiannual threat pattern and trend information analysis.22 Not only are ransomware payments increasing, but SARs related to ransomware are also setting a record pace. In the report, FinCEN identified bitcoin as the prevalent payment method for ransoms. FinCEN also held two ransomware-focused FinCEN Exchange events, published a notice requesting FIs expedite ransomware SAR reporting and requested comments on proposed BSA/AML requirements for certain transactions involving convertible virtual currency or digital assets with legal tender status.23

Virtual Currency

Finally, in what certainly appears to be a coordinated effort with FinCEN, OFAC published guidance for the virtual currency industry.24 OFAC’s guidance makes very clear that virtual currency-related activity is subject to OFAC’s framework25 expectations:

“OFAC sanctions compliance obligations apply equally to transactions involving virtual currencies and those involving traditional fiat currencies. Members of the virtual currency industry are responsible for ensuring that they do not engage, directly or indirectly, in transactions prohibited by OFAC sanctions, such as dealings with blocked persons or property, or engaging in prohibited trade- or investment-related transactions.”

Conclusion

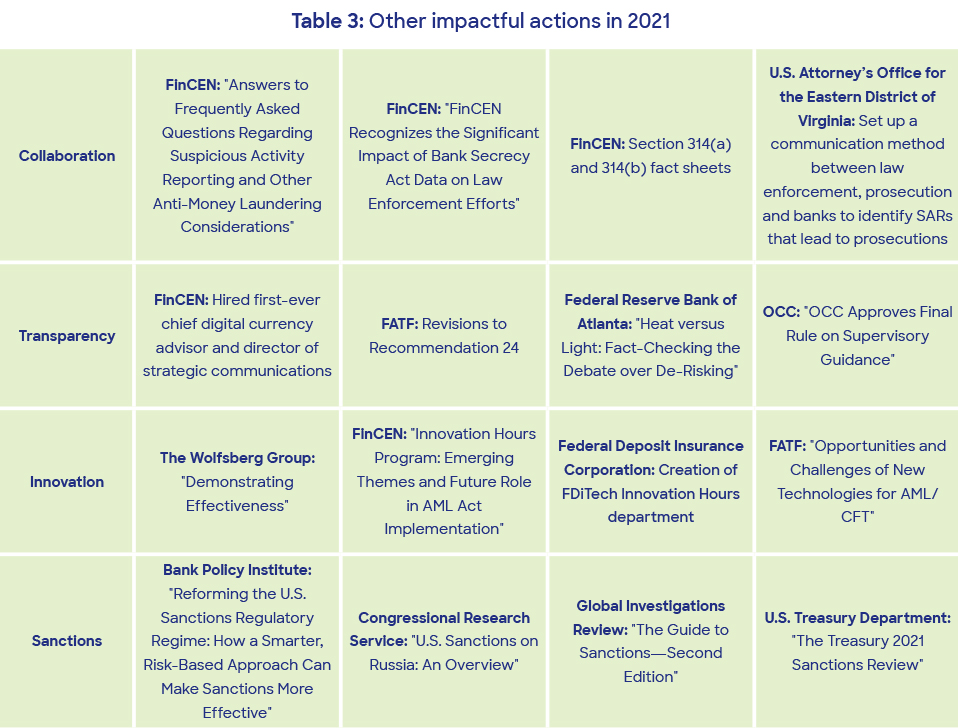

Certainly, there have been other regulatory updates in 2021 (see Table 3 above). The regulator updates mentioned above represent a snapshot of the direction the AML/CTF and sanctions industry is heading. Law enforcement is catching up with technology by providing guide rails for virtual currencies, regulators are permitting BSA officers more freedoms in building risk-based AML/CTF and sanctions programs with the ultimate goal of filing SARs that are more effective for law enforcement, and information sharing is in a spotlight. The year 2022 will certainly be like no other for the AML/CTF and sanctions industry.

Chris Bagnall, CAMS-FCI, CFE, Sojourn Technologies, Bagnall@sojourn-technologies.com

Amy Wotapka, CAMS, BSA officer, First American Bank, awotapka@firstambank.com

- “FinCEN Issues First National AML/CFT Priorities and Accompanying Statements,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, June 30, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-issues-first-national-amlcft-priorities-and-accompanying-statements

- “Federal and State Regulators Release Updates to the BSA/AML Examination Manual,” Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, February 25, 2021, https://www.ffiec.gov/press/pr022521.htm

- “Supervisory Guidance on Model Risk Management,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, April 4, 2011, https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2011/bulletin-2011-12a.pdf

- “Interagency Statement on Model Risk Management for Bank Systems Supporting Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering Compliance,” U.S. Federal Reserve, April 9, 2021, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/bcreg20210409a2.pdf

- Ibid.

- “Joint Statement on the U.S.-EU Joint Financial Regulatory Forum,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 29, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0084

- “United States,” Financial Action Task Force, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/countries/#United%20States

- “Offshore havens and hidden riches of world leaders and billionaires exposed in unprecedented leak,” Consortium of Investigative Journalists, October 3, 2021, https://www.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/global-investigation-tax-havens-offshore/

- “HR ll - Representative Tom Malinowski,” Malinowski House, October 6, 2021, https://malinowski.house.gov/sites/malinowski.house.gov/files/ENABLERS%20Act%20FOR%20INTRO_SIGNED.pdf

- Ibid.

- “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, August 2, 2017, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/countering-americas-adversaries-through-sanctions-act

- Stacy Cowley, “15% of Paycheck Protection Program Loans Could Be Fraudulent, Study Shows,” New York Times, August 17, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/business/ppp-fraud-covid.html

- “Fraud Section Enforment Related to the CARES Act,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 26, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/cares-act-fraud

- Katherine Chiglinsky, “Fintechs Found to Be Much More Likely to OK Suspicious PPP Loans,” Bloomberg, August 17, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-17/fintechs-found-to-be-much-more-likely-to-ok-suspicious-ppp-loans

- Carla Tardi, “80-20 Rule,” Investopedia, May 25, 2020, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/1/80-20-rule.asp

- “Coronavirus,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, https://www.fincen.gov/coronavirus

- “COVID-19 Resource Center,” Ballard Spahr, https://www.ballardspahr.com/Services/Initiatives/COVID-19-Resource-Center?utm_source=vuture&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2021%2F10%2F14%20nnno

- “Ransomware Payments in 2021 Already Dwarf Last Year’s Total, FinCEN Reports,” CoinChallenge, October 15, 2021, https://coinchallenge.net/2021/10/ransomware-payments-in-2021-already-dwarf-last-years-total-fincen-reports/

- “Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 1, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/ofac_ransomware_advisory_10012020_1.pdf#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Department%20of%20the%20Treasury%E2%80%99s%20Office%20of,be%20sanctioned%20or%20otherwise%20have%20a%20sanctions%20nexus.2

- “Updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 21, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/ofac_ransomware_advisory.pdf

- “Treasury Takes Robust Actions to Counter Ransomware,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 21, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0364

- “Ransomware Trends in Bank Secrecy Act Data Between January 2021 and June 2021,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/2021-10/Financial%20Trend%20Analysis_Ransomware%20508%20FINAL.pdf

- “The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network Proposes Rule Aimed at Closing Anti-Money Laundering Regulatory Gaps for Certain Convertible Virtual Currency and Digital Asset Transactions,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 18, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1216

- “Sanctions Compliance Guidance for the Virual Currency Industry,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, October 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/virtual_currency_guidance_brochure.pdf

- “A Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/126/framework_ofac_cc.pdf