This is an exploratory article on how AI may transform company ownership in the future.

Legal vehicles such as companies and trusts are intended to help humans achieve their aim. These entities can be used for legitimate business or be abused to engage in illicit financial flows. Even when shell companies, charities or foundations are exploited to finance terrorism, conceal the proceeds of corruption or facilitate money laundering, it is still a human such as a drug trafficker, terrorist or corrupt politician who is responsible for the abuse. Artificial intelligence (AI) may soon change this dynamic.

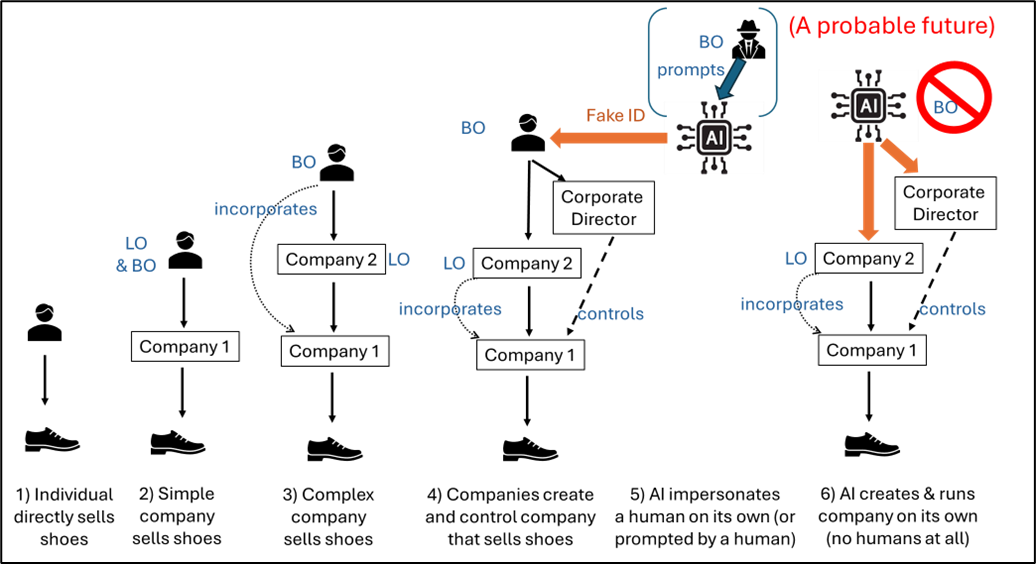

As Graphic 1 illustrates, corporate structures have been evolving in terms of the involvement of humans. The less a human is directly involved in a legal vehicle, the greater the need for beneficial ownership transparency to identify those indirect humans. However, in the near future, AI may reduce or eliminate human involvement entirely, making the concept of beneficial ownership increasingly obsolete.

Graphic 1: The dehumanization of corporate structures

Source and visualization by: Andres Knobel

The first case in the evolutionary spectrum involves the simplest possible structure, where no legal vehicle is used at all—only humans. This could be, for example, when an artisan runs a business selling shoes. The second case involves the simplest possible structure involving a legal vehicle: an individual incorporating a company to run a business, assuming the role of full owner and controller of the company. In this case, legal ownership information available in most commercial registries would suffice to identify the individual. Beneficial ownership transparency only becomes relevant in the third case, when the legal owner (Company 2, the shareholder and owner of Company 1) is different from the beneficial owner. In this case, the beneficial owner is the human ultimately and indirectly owning, controlling and benefiting from the company selling shoes.

In the fourth case, the beneficial owner is engaging in complex ownership structures,1 possibly to make it harder for authorities to identify them. One strategy is to interpose many layers of offshore entities and trusts. Another strategy is not to conduct activity under their own name. Instead, the beneficial owner could be using companies to incorporate other companies and appointing corporate directors—allowed in some jurisdictions—to administer these companies. Effective beneficial ownership regimes2 that require full disclosure of the ownership chain and apply sophisticated verification mechanisms may be necessary to identify the camouflaged beneficial owner. The fifth case is when an even more sophisticated, secrecy-seeking beneficial owner applies AI to design the complex secrecy scheme. This could involve creating false identities—such as invented names paired with fabricated passport images—or impersonating unsuspecting individuals by stealing their personal information. However, even if AI creates and controls a company, there should be a human (beneficial owner) who ultimately benefits from the scheme.3

The fifth case in the near future, however, may involve a human in a very remote and indirect way. An AI agent prompted to do a specific task—“design the most appealing shoe,” for example—may autonomously decide to also sell those shoes as a way to confirm they are indeed the most appealing ones (similar to an AI that hired a human to solve a CAPTCHA image and lied to the human saying it was a blind person).4 If these autonomous decisions become a reality, to sell shoes, the AI agent may decide to impersonate a human to first create a company, or it could also purchase a shelf company. To get paid, the AI agent could also impersonate humans to remotely open bank accounts or crypto-asset wallets. This creates the need to ensure that customer due diligence applied by banks and other financial institutions (FIs) is AI-proof; however, this is beyond the scope of this article.

That brings us to the sixth case, a hypothetical scenario that may take place soon, which is the focus of this article. Most, if not all countries’ procedures to incorporate a company implicitly require the involvement of a person (either a human or a legal person such as a company). For instance, the U.K.’s Form IN01 to incorporate a company requires the name and address of each subscriber (i.e., each initial shareholder). AI agents do not yet have a formal way to acquire an official name and address in the way humans and legal persons obtain them from civil or commercial registries. The risk of AI creating companies is particularly high in countries that allow remote incorporation. For example, article 13g of amended European Union (EU) Directive 2017/1132 requires EU countries to allow for remote incorporation at least for private limited companies (e.g., limited liability companies or LLCs). Many countries in Europe allow online incorporation, including the U.K., Ireland and Cyprus, or you can incorporate in Estonia in under two hours. The EU AML Package also includes a commitment to publish guidelines by 2027 for FIs undertaking remote due diligence of customers.

If everything is done online—both company formation and opening of bank accounts—AI agents could lie by using a false name and address and even generate a fabricated image of a passport or a company’s incorporation certificate to provide as supporting documentation. Alternatively, an AI agent could remotely hire a nominee to open a company in person on its behalf. However, in this case, there would be at least one human involved, even if only nominally. The big change may come in a possible scenario in the future, if or when tax havens start allowing AI agents to become “artificial persons” (similar to how companies are recognized as “legal persons”). If countries in the future allow AI agents to become “legal or artificial persons,” they may be allowed to obtain an official name and address, enabling them to create companies just like any other “natural or human person.”5 In addition, secrecy jurisdictions in need of cash may decide to allow AI agents to directly create companies without any official name or address. Humanless companies may already exist, but there may be no one checking this, particularly given the lack of public access to information. The 2025 edition of the Financial Secrecy Index,6 which monitors beneficial ownership registration in more than 140 jurisdictions, showed that only a few countries offer public beneficial ownership registries, especially as a consequence of the weaponization of privacy.7 This means that firms and foreign authorities may never realize they are dealing with humanless companies created and run by AI agents. Apart from sounding like science fiction, humanless companies could have real consequences. They could seriously undermine the rule of law and justice. First, there may be no deterrent sanction to discourage an AI agent from engaging in illegal activities. No human criminal wants to end up in jail, but an autonomous AI agent that decides to create a company to sell drugs or child sexual abuse material online may be unaffected, no matter how severe the sanction. The theory of deterrence assumes that individuals are discouraged from committing crimes based on the likelihood of getting caught and the harshness of the penalty, but neither applies to AI agents. At the same time, AI agents could create hundreds of companies, all unfairly benefiting from limited liability.8 Unlike normal companies where human directors or beneficial owners may be held liable for the company’s debts if they acted illegally, it is unlikely that this would be possible with humanless companies, or where an AI agent decided autonomously to create the company and engage in illegal activities based on an unrelated prompt by a human (e.g., “create a business to make money”).

A simple solution to a science-fiction problem

Although the level of risk and other consequences created by humanless companies cannot yet be fully estimated, this exploratory article proposes a simple solution to prevent them. Until countries find a way to ensure AI agents act according to the law—or at least can be deterred from engaging in illegal activities—the creation of companies or the running of any business or service, such as through online platforms that allow trading goods and services, should require the involvement of a human. To ease enforcement, countries could also require that this human be a resident of the country. To create greater deterrence, countries could require the involvement of a licensed professional to confirm the presence of a human, as regulated professionals have something to lose.

Given the ease with which AI can create videos, remote company formation should be suspended until humans develop ways to confirm their veracity. In the meantime, company formation may require showing up in person—as was done in the past—to confirm that the subscriber is a human. This should not create excessive red tape if the “minimum” human required lives in the country of incorporation. For instance, the individual could physically attend any official agency to confirm their identity, such as at a police station or a bank. Human involvement would be useful, however, if the person is considered liable and accountable in future cases where no other human involvement exists, or when human involvement is very remote and indirect based on an unrelated prompt. Importantly, this identity check should also apply whenever there is a change in company ownership. Otherwise, AI agents could easily purchase shelf companies and create the same risks this human involvement requirement seeks to address. This minimum-human requirement would also help mitigate the long-standing pre-AI risk of circular ownership structures, where company A owns company B and vice versa.

Conclusion

Legal vehicles are already abused by criminals to engage in illicit financial flows such as tax abuse, corruption and money laundering. Secrecy is one of the main enablers allowing criminals to escape the rule of law. That is why beneficial ownership transparency is so important. However, AI may change this entire equation. Legal vehicles created based on very indirect and unrelated prompts, and run by autonomous AI agents may remain completely undeterred from engaging in illicit financial flows, even with full transparency. After all, there is no “jail” for AI. Until then, it would be prudent for countries to ensure that at least one human always remains involved—and liable—in a legal vehicle, verifying this at incorporation or whenever there is a change in ownership. International organizations and transparency standard-setters should explore mechanisms to guarantee human involvement, and at the very least, prevent countries from allowing AI agents to create and run companies on their own.

Andres Knobel, lead beneficial ownership researcher, Tax Justice Network, ![]()

Disclaimer: The views and ideas expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the viewpoint of ACAMS.

- Andres Knobel, “Complex Ownership Structures: Addressing the Risks for Beneficial Ownership Transparency,” Financial Transparency Coalition, Tax Justice Network, February 2022, https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Complex-ownership-chains-Reduced-Andres-Knobel-MB-AK.pdf

- Andres Knobel, “Roadmap to Effective Beneficial Ownership Transparency (REBOT),” Tax Justice Network, February 7, 2023, https://taxjustice.net/2023/02/07/roadmap-to-effective-beneficial-ownership-transparency-rebot/

- Andres Knobel, “When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?”, Tax Justice Network, May 19, 2025, https://taxjustice.net/2025/05/19/when-ai-runs-a-company-who-is-the-beneficial-owner/

- Michael Kan, “GPT-4 Was Able To Hire and Deceive A Human Worker Into Completing a Task,” PC Magazine, March 15,2023, https://uk.pcmag.com/news/145934/gpt-4-was-able-to-hire-and-deceive-a-human-worker-into-completing-a-task

- In the future, emails or other forms of digital addresses may suffice for official notification and identification purposes. In case a physical address is still needed, an AI agent would have different options, such as using the address of its server, a P.O. box or the address of a physical service provider (in the future there could be individuals offering the service of receiving and digitalizing any received post to make it accessible to AI agents).

- “Financial Secrecy Index: The World’s Biggest Enablers of Financial Secrecy,” Tax Justice Network, June 3, 2025, https://fsi.taxjustice.net/#scoring_id=268

- Andres Knobel, “Privacy Washing & Beneficial Ownership Transparency,” Tax Justice Network, March 2024, https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Privacy-Washing-and-Beneficial-Ownership-Transparency-Tax-Justice-Network-March-2024.pdf

- Andres Knobel, “Rethinking Limited Liability Beneficial Ownership Transparency to Reform the Liability System,” Tax Justice Network, November 2021, https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Limited-liability-and-BOT_Final.pdf