An elephant is poached every 30 minutes.1 An African rhino dies for its horn every eight hours.2 One in every five fish is caught illegally.3 In some African and South American countries, 50% to 90% of the wood harvested is illegally traded.4 These are illegal wildlife trade (IWT) statistics, which refer to the commerce of products derived from nondomesticated animals or plants usually extracted from their natural environment or raised under controlled conditions. IWT can involve the trade of living or dead wildlife animals, including their skins, bones, meat or other body parts. Interpol estimates this market to generate approximately 20 billion US dollars per year,5 placing wildlife trafficking as the fourth most profitable illicit activity, after drugs, counterfeit goods and human trafficking. This scourge, like all illicit trafficking, is shifting, adapting and growing. In addition to threatening the extinction of species, it also hinders sustainable economic development. IWT has close links to transnational organised crime networks, corruption and illicit money flows. For example, through money laundering, IWT poses a threat to regional and national security. EU policies to support a sustainable development around the world are directly related to the protection of global biodiversity and the efforts to strengthen good governance.

Globalisation is creating new transportation networks and infrastructure that allows people access to remote wildlife. Europe finds itself as the bridge between Africa and Asia, and at times as the final destination. The old continent is aware of the importance of the challenges posed by IWT and it has adopted strict trade rules for endangered species on Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 and by implementing other regulations. Europe continues to invest in several ways despite sometimes mixed results.

Impact From the COVID-19 Pandemic

The current pandemic has cost the lives of more than four million people and an estimated 16 trillion US dollars, or roughly 90% of annual gross domestic product of the US.6 On the other hand, between 2019 and 2020, the confiscation of pangolin scales fell from 100 tons to 20 tons, and rhino horns seized in 2020 were one-tenth less than the previous year.7 The numbers are encouraging and are in part, among other things, due to the disruption of trafficking networks as countries closed their borders, instituted lockdowns and tightened surveillance. However, the consumption ban is unlikely to have a long-lasting impact on wildlife trafficking since these laws were implemented to fight the pandemic and borders will not be closed forever. Furthermore, some central governments have little control over the remote areas where illegally wildlife is hunted. For example, the Golden Triangle of Southeast Asia, which spans the borders of Laos, Thailand and Myanmar, is a poaching hot spot and the mecca of opium cultivation. In response, 241 leading animal welfare and conservation organisations8 are requesting the World Health Organisation to ban the sale and trade of wildlife for food trade due to public health concerns. Nevertheless, current measures ignore the complexity of legal wildlife trade. For example, in Operation Lake V, 387kg of glass eels and 25kg of adult eels valued at about 1.241 million euros were seized. This operation was coordinated by Europol between November 2020 and June 2021 and it involved law enforcement authorities from 24 countries, including the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF, for its acronym in French), the EU Wildlife Enforcement Group and the EU Food Fraud Network.9 This seizure indicates that these products were stockpiled during the pandemic in anticipation of a resurgence in demand, as restrictions relaxed. Reptiles and amphibians are not necessarily the most charismatic animals, but like elephants, tigers and rhinos, they are the most affected by this crime and they play an essential role in local ecosystems.

Old and New Platforms

Meanwhile, sea freight has been favoured by wildlife traffickers due to disruptions in air traffic and fewer opportunities for smuggling on passenger ships. Criminals conceal wildlife and wildlife products by shipping them with legal products, making them difficult to detect. In addition, the focus of cargo screening is primarily to identify drugs, explosives and other contraband, so illegal wildlife is a lower priority. At Charles de Gaulle airport, only 2.5% of luggage is searched for animal products,10 which seems to be a rather inefficient measure. Moreover, some countries seem to play a more important role in the illegal trade. In 2019, 79% of the seizures were made by just five countries in Western Europe: France, Germany, UK, Spain and the Netherlands.11 Hence, the traffickers try to transit as much as possible through Eastern European countries where the controls are even less successful.

Trade in wildlife and wildlife products have intensified in online platforms, a main route to market, even prior to the pandemic.12 Real efforts have been made by social media giants, such as Facebook, Instagram, Google, TikTok, Pinterest and others, to combat IWT through the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online. These giants represent 11 billion account user worldwide and have blocked or removed more than 11 million ads that violate IWT policies.13 In 2019, the EU funded an initiative to counter surging wildlife cybercrime, which aims to train European customs and police officers to detect and stop wildlife trafficking but also online delivery and technology companies so that wildlife traffickers do not exploit their services.14 They rely on the EU-TWIX database, which contains centralised data on seizures and offences reported by all 27 EU member states, Switzerland, Ukraine and the UK.

However, criminals can migrate to other available platforms and adjust their methods to evade detection, such as changing terminology and using word codes. In addition, encrypted or undetected online transactions—especially US Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects online businesses from liability for illegal activities on their platforms15—make online commerce an arduous task to manage.

Worldwide and European Regulations

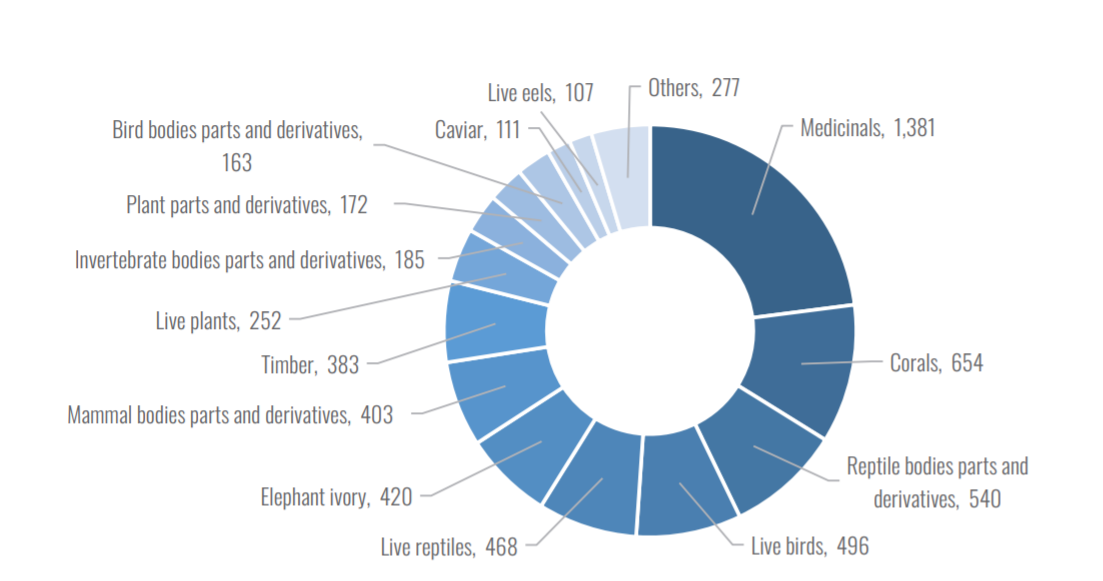

Appropriate legislation is one of the primary challenges to combat wildlife trafficking effectively. At the international level, several regulations govern wildlife trade. The objective of international trade laws for wildlife focus on protecting endangered species. The main regulation is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), to which the signatories adhere voluntarily. European member states use their own national laws and enforcement agencies to implement this convention. Even if CITES is legally binding, its success depends on the voluntary participation of states and their application according to sometimes conflicting or non-existent rules. For example, the types of wild animals and plants protected may differ per country, as do the conditions permitted by trade and even when clear rules are enacted, they have little effect. Illegal importation into the EU of bushmeat and live animals, as per CITES’-listed wildlife in the EU, occurs even though CITES is ratified by all member states. In 2018, EU member states reported 6,012 seizures of specimens that correspond to the 16,740 species listed on CITES’ list. The following figure shows all seizure records reported by EU member states across commodity groups in 2018 (based on number of seizure records).16

Figure 1: The main types of commodities seized in the EU in 2018

To curb these distressing numbers, the UE launched the project Successful Wildlife Crime Prosecution in Europe (LIFE SWIPE) in 2020. With a budget of the 3,186,175 euros, it aims to enforce better implementation of EU environmental regulations and more successful prosecution of crimes with concrete objectives and results to be reached before 2023.17

For wildlife trafficking enforcement actions to be successful, the penalties must be appropriate for the crime. Private person and businesses who profit from this trade must face effective prison sentences and fines commensurate with the profits generated. A good example would be the Polish legislation which imposes a fine on smugglers based on the amount calculated as a percentage of annual income, up to 10%, but no less than 250 euros and no more than 5,000,000 euros and three months to five years of imprisonment.18

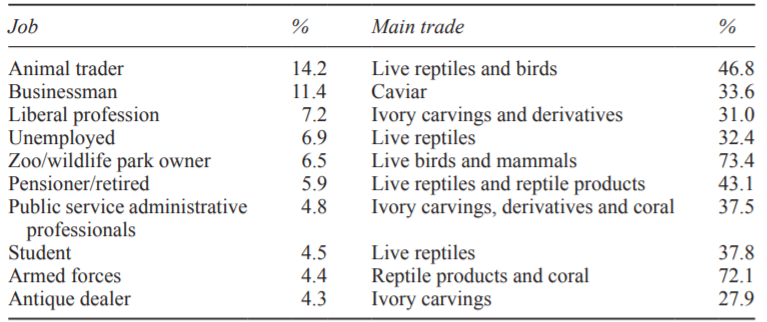

Table 1: Job and main trade of perpetrators

Reputational risk should also be calculated. IWT is often linked to drug trafficking, money laundering, human trafficking, financial crime, or climate change. Exposing companies to these illegal markets in the media should motivate them to implement effective regulatory policies. Criminal penalties for key officers of these companies could also be considered.

Placing People Front and Centre

Taking advantage of each other's abilities is at the heart of new policies to combat wildlife trafficking, and it is important to get to the root of the problem by involving the local populations, those who are the first witnesses and/or participants of IWT. Their knowledge of the topography and poaching techniques would be a great asset in the fight against wildlife trafficking. For example, it is important to consider that most Asian poachers receive five to 10% of the retail value for the animal parts they poach20 and the rhino horn price is estimated at 65,000 US dollars per kilogram on the Asian black market.21 Hence, a poacher can earn up to 6,000 US dollars for a rhino horn, when over 80% of the population in the region lived with less than 5.50 US dollars per day in 2015.22 The efforts of the UE must be concentrated on sensitizing the indigenous population, providing the basic services and economic opportunities to communities that are at risk of being exploited by criminal networks for illegal wildlife trade.

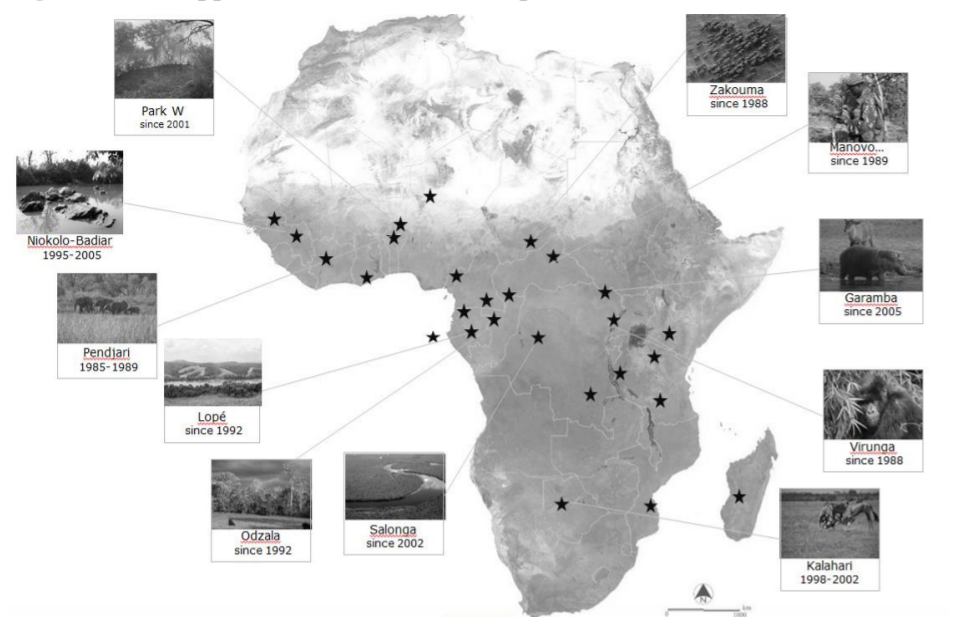

In November 2021, the old continent launched the Green Team Europe Initiative in partnership with Southeast Asian countries to protect the environment. With an initial grant of 30 million euros from EU’s budget, the initiative aims to promote joint commitment to the prevention of illegal logging, wildlife trafficking, sustainable and long-lasting transformation toward circular, climate-neutral and environmentally sustainable economies, as well as resilient ecosystems.23 This aid echoes the 160 million euros spent on ongoing projects by the EU to establish and safeguard protected areas in Africa. The figure below highlights some of the regions where the EU has been a supporter of African countries’ work in establishing and managing protected areas.

Figure 2: EU’s support for African national parks

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic could have made us hope that illegal animal trafficking would subside. However, like the virus, poachers and those who profit from illegal trade are mutating and are only partially impacted by the efforts by European and global authorities. To be more effective, the latter must address illegal wildlife trade as a public health issue by:

- Effectively implementing existing legal instruments.

- Strengthening border control procedures by providing the necessary means, i.e. human, technological and financial means to its professionals.

- Basing their policies on ‘wildlife forensic science’, a field of investigation that offers great potential to mitigate wildlife trafficking.

In an increasingly globalised world, illegal wildlife trade can no longer be considered a developing country’s problem. As one of the world's largest and wealthiest economies, in addition to strong technological expertise, the EU has a moral duty to combat IWT. In 2019, a Eurobarometer survey revealed that 77% of European citizens ‘totally agree’ that it is their responsibility to look after nature, with 71% saying that nature protection areas are ‘very important’ for the conservation of endangered animals—the ball is in our court.

Xavier Aubert, senior analyst, Deloitte, xavieraubert11@gmail.com

- David Gorin, "Drama and emotion in an elephant relocation mission (South Africa)," Journal of African Elephants, 11 December 2019,

https://africanelephantjournal.com/drama-and-emotion-in-an-elephant-relocation-mission/#:~:text=Rapacious%20poaching%20continues%20despite%20a,elephants%20are%20poached%20than%20born. - Ray Dearlove, "Every eight hours, a rhinoceros is slaughtered in South Africa," The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 June 2017, https://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/every-eight-hours-a-rhinoceros-is-slaughtered-in-south-africa-20170612-gwp9ev.html#:~:text=Every%20eight%20hours%2C%20a%20rhinoceros%20is%20slaughtered.&text=While%20the%20number%20of%20rhinos,white%20rhinos%20and%202500%20black

- Jessica Aldred, “Explainer: Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing,” China Dialogue Ocean, 3 June 2021, https://chinadialogueocean.net/11813-explainer-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing/

- “ILLEGAL LOGGING,” WWF, https://wwf.panda.org/discover/our_focus/forests_practice/deforestation_causes2/illegal_logging/

- “Wildlife crime,” Interpol, https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Environmental-crime/Wildlife-crime

- David M. Cutler, Ph.D. and Lawrence H. Summers, Ph.D., "The COVID-19 Pandemic and the $16 Trillion Virus," US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 2 November 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7604733/

- Dina Fine Maron, “Wildlife seizures are down—and an illicit trade boom may be coming,” 15 March, 2021, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-seizures-dropped-in-2020-but-an-illicit-trade-boom-may-be-coming?loggedin=true

- "Open letter to World Health Organisation," Lion Coalition, 4 April 2020, https://lioncoalition.org/2020/04/04/open-letter-to-world-health-organisation/

- “Eels shipped by air found in operation Lake-V,” Europol, 19 November 2021 https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/eels-shipped-air-found-in-operation-lake-v

- Jos Noordhuizen, Helmut Surborg &Frans J.M Smulders, “On the efficacy of current biosecurity measures at EU borders to prevent the transfer of zoonotic and livestock diseases by travelers,” Tandfonline, 28 May 2013, https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2013.826883

- Marius Daea, "Investigation reveals illegal wildlife trade is rife in Eastern Europe," Earth Journalism Website, 1 July 2020, https://earthjournalism.net/stories/investigation-reveals-illegal-wildlife-trade-is-rife-in-eastern-europe

- Rene Ebersole, “The black-market trade in wildlife has moved online, and the deluge is 'dizzying',” National Geographic, 18 December 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/how-internet-fuels-illegal-wildlife-trade

- “About The Coalition,” Coalition To End Wildlife Trafficking Online, https://www.endwildlifetraffickingonline.org/about

- 47 U.S. Code § 230 - Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

- 47 U.S. Code § 230 - Protection for private blocking and screening of offensive material,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230

- “An overview of seizures of CITES-listed wildlife in the European Union,” TRAFFIC, January to December 2018, https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/12745/eu-seizures-report-2020-final-web.pdf

- "Successful Wildlife Crime Prosecution in Europe," European Commission, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/index.cfm?fuseaction=search.dspPage&n_proj_id=7581

- Tobias Garstecki, "Implementation of Article 16, Council Regulation (EC) No. 338/97, in the 25 Member States of the European Union," TRAFFIC Europe, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/cites/pdf/studies/sanctions_wildlife_trade.pdf

- Daan P. van Uhm, “Illegal Wildlife Trade to the EU and Harms to the World,” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305441741_Illegal_Wildlife_Trade_to_the_EU_and_Harms_to_the_World

- "Wildlife Trafficking & Criminal Profits," Poaching Facts, https://www.poachingfacts.com/

- "Rhino Horn Price – How much is a Rhino Horn Worth?" Rhino Rest, 6 September 2020

https://www.rhinorest.com/rhino-horn-price - "Nearly Half the World Lives on Less than $5.50 a Day,” The World Bank, 17 October 2018, PRESS RELEASE, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/10/17/nearly-half-the-world-lives-on-less-than-550-a-day

- "European Union launches a Green Team Europe Initiative in partnership with South East Asia," European Commission, 18 November 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_6111

- "Analysis and Evidence in support of the EU Action Plan against Wildlife Trafficking," European Commission, 26 February 2016, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52016SC0038

Thank you for sharing the Article, a lot of useful information.