When walking along the Seine in Paris, one can see drawings on a wall depicting unusual icons. What appear to be children’s drawings at first are actually images representing the 17 Sustainable Development Goals agreed upon by UN member states in 2015. These ambitious and high-level objectives are to be achieved by 2030 with all countries working together in global partnership.1

From UN Goals to the European Anti-Money Laundering Directives

At the end of 2016, the European Commission confirmed that the Sustainable Development Goals were already being pursued through many of the EU's policies and integrated in all the Commission's priorities.1 This explains why goal eight―which includes ending human trafficking and promoting full, productive and decent work for all―is incorporated in the last directive on combating money laundering by criminal law EU 1673/2018, also referred to as the Sixth AML Directive (6AMLD).2 Laundered proceeds from human trafficking must be reported as of June 2021.

The European directives require that the financial sector in particular—as well as other non-financial sectors—take concrete steps to align in writing and in spirit with these objectives. This article will discuss key risk indicators in relation to forced labour. These key risk indicators should enable obliged entities of the EU to investigate, mitigate and ultimately report their suspicions to their national authorities.

Forced Labour Is a Global Issue

Forced labour is a form of modern slavery. It refers to work that is performed involuntarily as well as under the threat of a penalty. The victims involved in trafficking situations are coerced to perform work under threat of violence, coercion or intimidation, or by more subtle means aimed at controlling their victims.3

In 2016, 40.3 million people were victims of modern slavery in the world, including nearly 25 million victims of forced labour from which 16 million were exploited in the private sector (i.e. domestic work, construction and agriculture) and 4.1 million people were estimated to be in forced labour.4

In Western Europe

The police in Western Europe recently arrested a criminal network that enslaved Moldovan nationals by forcing them to work for private companies in France. The criminals provided the 40 Moldovan migrants with counterfeited Romanian identity cards (Moldavia is neither part of the EU nor the Schengen area) and kept their real passports as a guarantee. The smuggled workers were then forced to work in the construction sector. Deprived of real identity papers, the Moldovans had no choice but to cooperate and accept their tragic fate. They worked 55 hours per week and were paid only 60 euros a day. They had to cope with dreadful working and living conditions and were deprived of normal workers benefits, such as social security. The illegal profits of the Moldavian traffickers were estimated at almost 14 million euros. The suspects laundered the criminal assets through eight shell companies, most of them based in France.5

The Role of the Financial Sector

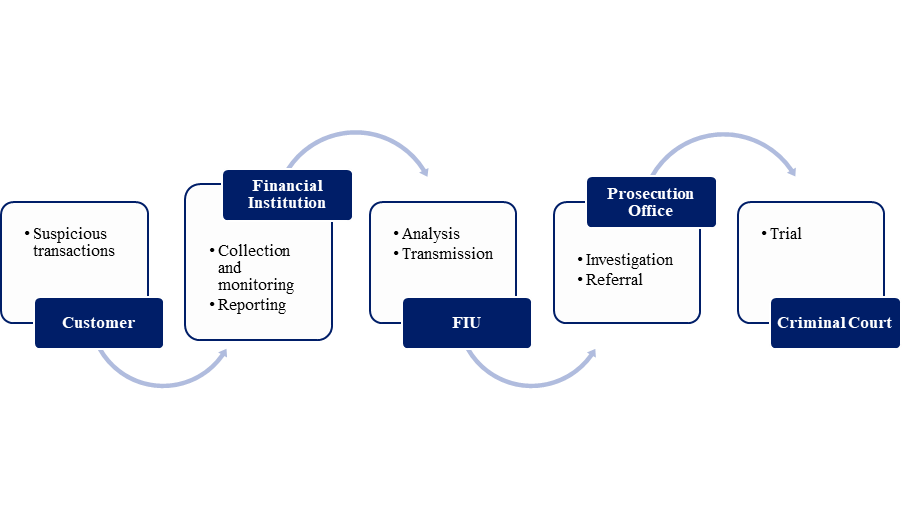

Financial institutions are required by law to implement an anti-money laundering (AML) regime in order to detect activities with a potential nexus to criminal activities. Financial institutions disclose their suspicions through suspicious transaction reports (STRs) to their respective financial intelligence unit (FIU). These reports are the cornerstone of many financial investigations within the public and private sectors.

According to Europol, ‘Money Service Businesses and postal services are the most widely used modus operandi for laundering the proceeds from THB [the trafficking of human beings].’6 National FIUs can uncover meaningful patterns in relation to criminal activity that would otherwise not be evident to individual financial institutions. The compilation of data from various reporting bodies enables national FIUs to provide law enforcement with valuable information. Criminal investigations can be opened on the basis of information transmitted by FIUs and can result in legal action, in the seizure and confiscation of the proceeds from criminal conduct and ultimately, in the rescue of victims and the conviction of traffickers.7 Financial investigations may produce strong and concrete evidence, even when the illicit proceeds obtained from criminal conduct have disappeared. Courts of law regularly refer to evidence gathered during financial investigations to convict defendants.8

The following figure represents the trajectory of a suspicious transaction reported by a financial institution and taken to a criminal court for trial.

Figure 1: From Information to Intelligence and Evidence Model

The Five Key Risk Indicators

The starting point for effective financial investigations is the awareness and use of accurate financial indicators and transactional red flags indicative of human trafficking for the purpose of labour exploitation.9 The following key risk indicators (KRIs)10 may increase the likelihood of effective reporting and provide law enforcement with actionable intelligence. It is important to note that ‘No one indicator alone is likely to confirm money laundering from human trafficking.’11

KRI #1: Behavioural Indicators

Behavioural indicators refer to red flags that may be identified via face-to-face interactions with victims or traffickers. These may be identified based on coercive behaviours by a potential trafficker acting on behalf of a victim such as the use of an interpreter at account opening or for conducting transactions. This also includes the appearance of a potentially trafficked individual, such as signs of physical abuse.

To mentally or physically coerce or control their victims, traffickers may use methods that consist of ‘breaking the human spirit,’ such as relocation, food denial, sleep denial, emotional and physical threats, or brainwashing. 12

KRI #2: KYC Indicators

KYC indicators refer to red flags that may be identified through the collection of customers’ information. According to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the following is one of the key issues to consider:

‘Wider contextual information can prove useful in identifying signs of trafficking. Financial institutions may hold passport information, utility company information (or lack of it) and residency details. Combined with financial data, they help to give a rich picture of the launderer, perpetrator and/or victim’s financial flows and behaviour.’ 13

KYC indicators may include:

- When viewed on Google Street View, a property that could only comfortably accommodate two or three people at most but seems to have more people living there

- Reports or indication of cheap labour or unfair business practices toward an entity

- Accounts of foreign workers or students where the employer or employment agency serves as a custodian

- One attorney claiming to represent multiple undocumented immigrants detained at different locations

- Invalid work contracts, group travel for conferences, seminars and study tours

KRI #3: Transactional Indicators

Transactional indicators refer to red flags that may be identified via the monitoring of financial operations. The following transactional indicators specifically relate to labour exploitation:

- A high percentage of income withdrawn quickly after receipt in the accounts

- Analysis of ATM activity showing that their ATM usage often occurred at the same machine and at the same time, suggesting that a third party is in control of their cards

- A lack of living expenses, such as food, petrol, utilities and rent

- No evidence of payment of taxes or of other payments to a tax authority or to other government or regulatory body typically associated with legitimate full-time employment of workers

- The purchase of a one-way flight ticket from a high-risk country by a non-family member

- Payment for a visa permit by a non-family member

- Payments to labour agencies, recruiters or employment websites, especially if those entities are based overseas

- Personnel numbers and costs, if known through the provision of information by the entity, is not in line with wages paid out or what is known about the entity

- Repeated (at least weekly) transfers of funds to the same third party (where known), often in round amounts

- The customers receive weekly income from an agency

- Non-payment of taxes, workman’s compensation and other fees to a tax authority

- Rate of pay for each pay period is identical (no changes for overtime, vacation, sick leave, bonus payments, etc.) in jobs where that would not be expected

- Recurring payments for wages at unreasonably low amounts (e.g. much lower than the minimum wage scale)

- Loans provided by a shareholder to the related legal person and subsequent transfer back and fictitious loans

- Payments to employment or student recruitment agencies that are not licensed/registered or that have labour violations

The following transactional indicators may apply to all forms of human trafficking, including labour exploitation:

- Common mobile number, address and employment references being used to open multiple bank accounts on different names

- Customer makes deposits/withdrawals or otherwise generally operates an account accompanied by an escort, handler or translator (who may hold the customer’s ID)

- High and/or frequent expenditure at airports, ports, other transport hubs or overseas, inconsistent with customer’s personal use or stated business activity

- Income received and immediately withdrawn in cash

- Newly opened customer account appears to be controlled by a third party, including forms completed in different handwriting and/or the customer reads their address from a form

- Payments to logistics, airlines, coach companies, car rental or travel agents inconsistent with customer’s personal use or stated business activity

- Relatively high or recurrent expenditure on items inconsistent with customer’s personal use or stated business activity, such as food, necessities or accommodation for workers

KRI #4: High-Risk Business Lines

Labour exploitation predominantly occurs in nine high-risk business types, although these vary considerably by geography and types of exploitation.14 It is worth noting that the following list is not comprehensive and that the indicators may be applicable to other types of exploitation as well (e.g. sexual exploitation).

- Entertainment: Recreational facilities

- Manual labour: Domestic work, agriculture and animal husbandry, construction, landscaping, commercial cleaning services, factories and manufacturing, forestry and logging, janitorial services, production and trade, recruitment agencies

- Sales: Outdoor solicitation, travelling sales crews

- Food and service: Restaurants, catering, grocery shops

- Health and beauty: Healthcare, nail salons, cosmetic clinics

- Travel: Hospitality, travel agencies, vehicle rentals, airlines

- Retail: Non-unionized stores, retail and small businesses

- Financial: Accounting firms, insurance companies, tax consultancy firms

- General illegal activities: Peddling and begging, illicit activities15

KRI #5: Geographical Risk Indicators

Although the geographical routes and trafficking flows are complex and affect all countries around the globe, it is important to consider geographical risk indicators. Countries may be divided into three categories: country of origin (i.e. the country of nationality), transit country (i.e. the country through which trafficked individuals pass through in order to enter a country of destination) and country of destination (i.e. the country that is a destination for trafficked individuals where the exploitation takes place).

According to the European Commission, the member states with the highest proportion of registered victims trafficked for labour exploitation were the following:

- Malta: 82%

- Portugal: 52%

- Belgium: 51%

- Ireland: 47%

- Poland: 47%

EU victims of labour exploitation come predominantly from the following countries:

- Poland: 67%

- Latvia: 62%

- Portugal: 61%

- Cyprus: 50%

- Lithuania: 45%

Finally, the following are the five non-EU citizenships with the highest proportion of victims:

- Sudan: 88%

- Eritrea: 54%

- India: 53%

- Bangladesh: 46%

- Pakistan: 39%

It is worth highlighting that the true extent of trafficking of human beings remains unknown and that the data available only appears to be the tip of the iceberg. As the European Commission points out, “The actual number of victims is likely to be significantly higher than the number registered and reported in data collections.”16

Conclusion

There is a clear benefit of including financial investigations in anti-trafficking responses. Financial institutions and AML practitioners play a key role in the fight against the trafficking of human beings. A careful financial investigation that properly follows the trail of money and other assets can reveal the complex structure of major criminal organisations and can eventually lead to the seizure and confiscation of criminal proceeds and the recovery of proceeds for victims. It also appears to be a prerequisite for a high-profile criminal investigation to ensure just and effective punishment for perpetrators and the recovery of proceeds for victims. Therefore, it is crucial to raise awareness and acquire knowledge about financial indicators and transactional red flags to address this global issue that knows no borders. In this regard, it is worth mentioning that ACAMS has developed a free self-paced online course and certificate with the Liechtenstein Initiative for Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking (FAST Initiative) enabling professionals from the financial sector to step in to fight against modern slavery and human trafficking.17

- “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EUR-Lex, 22 November 2016, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2016%3A739%3AFIN

- Once the directives are transposed, they become part of the national laws of each of the 27 European member states.

- “Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29),” International Labour Organization, 1930, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029

- “Financial Flows from Human Trafficking,” Financial Action Task Force and APG, July 2018, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/human-trafficking.html, 9.

- “Exploitation on the Construction Site: 38 Arrested in France, Romania and Moldova for Abusing Migrant Workers,” Europol, 25 February 2021, https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/exploitation-construction-site-38-arrested-in-france-romania-and-moldova-for-abusing-migrant-workers

- “The THB Financial Business Model, Assessing the Current State of Knowledge,” Europol, July 2015, https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/eu-policy/thb-financial-business-model_en

- “International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation,” Financial Action Task Force, 2012, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/fatfrecommendations/documents/fatf-recommendations.html. See Recommendations 20 and 29.

- For examples of successful confiscation, compensation for victims, and criminal cases initiated on the basis of financial intelligence, see “2019 Annual Report Trafficking and Smuggling of Human Beings, Empowering Victims,” Myria, 28 May 2020, https://www.myria.be/en/publications/2019-annual-report-trafficking-and-smuggling-of-human-beings

- “Following the Money Compendium of Resources and Step-by-Step Guide to Financial Investigations Related to Trafficking in Human Beings,” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, October 2019, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/438323; “Financial Flows from Human Trafficking,” Financial Action Task Force and APG, July 2018, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/human-trafficking.html.

- For case studies, see “Financial Flows from Human Trafficking,” Financial Action Task Force and APG, July 2018, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/human-trafficking.html, 26-32 and 56-64.

- Ibid., 19.

- “Human Trafficking Detection for Financial Institutions”, OnCourse Learning, 2019, https://www.oncourselearning.com/resource/human-trafficking-detection-financial-institutions/, 11-12.

- “Financial Flows from Human Trafficking,” Financial Action Task Force and APG, 2018, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/human-trafficking.html, 19.

- Ibid, 58-59.

- “Following the Money: Compendium of Resources and Step-by-Step Guide to Financial Investigations Related to Trafficking in Human Beings,” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, 7 November 2019, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/438323.

- “Data collection on trafficking in human beings in the EU,” European Commission, September 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/sites/antitrafficking/files/study_on_data_collection_on_trafficking_in_human_beings_in_the_eu.pdf

- Fighting Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking,” ACAMS, https://www.acams.org/en/training/certificates/fighting-modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking#learning-points-7fe6cdc6.