A month after the invasion of Ukraine, more than seven million people had been displaced as a direct result of the war, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM).1 The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) highlighted that most displaced people and refugees are women and children. According to UNICEF, of the country’s estimated 7.5 million Ukrainian children, 4.3 million have been displaced, and 1.8 million have crossed the border into neighbouring countries.2 Armed conflicts have shown that criminals profit from the chaos of large-scale population movements and the desperation of war, increasing vulnerabilities and providing opportunities to exploit displaced people and refugees. As a result, children are particularly exposed to human trafficking, with criminal networks operating between Ukraine and countries in Europe as well as Central Asia. As the conflict in Ukraine continues to unfold, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) highlighted that displaced people and refugees are particularly exposed to these criminal networks.3 According to the Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 by the US Department of State,4 Ukraine has been recognised as a source, transit and destination country for victims subjected to human trafficking.

The trafficking of human beings increases dramatically in times of conflict and children face considerable risk of exploitation, especially those who remain in residential institutions or those who have fled to the streets. Armed conflict and community violence can also leave families particularly vulnerable to traffickers seeking to recruit children for financial gain by placing them in institutions located in areas less-affected by conflict and by manipulating families to believe that their children would be safer and have better opportunities. This can result in mass migration, which is a major driving factor exacerbating the issue of institution-related trafficking. The combination of conflict and migration results in a significant number of unaccompanied migrant and refugee children, who may be placed in different institutions along the journey to a new destination or country. These institutions may not adequately protect children, thus exposing them to human trafficking. As the European Commission highlighted, “trafficking networks abuse asylum procedures and use reception centres to identify potential victims.”5

What is a Residential Institution?

A residential institution refers to a residential setting where children are compelled to live isolated from the wider community with other unrelated children, such as orphanages, compound/cluster facilities, centres for unaccompanied and migrant children, residential health facilities, psychiatric wards, as well as residential schools for students who have physical or mental problems and boarding schools. Although the true figure may be much higher due to gaps in global statistics, the Lumos Foundation claims there could be up to eight million children living in residential institutions worldwide.6 According to the Save the Children organisation, “most children in what are known as orphanages or children’s homes are not in fact orphans. At least four out of five children in institutional care have one or both parents alive.”7 According to UNICEF, almost half of the children have disabilities.8

Children and Institution-related Trafficking

The EU Commissioner for Home Affairs, Ylva Johansson, emphasised that there are “reports of criminals taking orphans from orphanages in Ukraine. Crossing the border pretending that they are relatives to the child and then using them for trafficking purposes.”9 Whilst the Trafficking in Persons Report 2014 by the US Department of State noted that “children in orphanages and crisis centres continue to be particularly vulnerable to trafficking within Ukraine,”10 the link between children’s institutions and human trafficking was recognised by the UN General Assembly in 2019.11 The children caught in the crossfire of the invasion in Ukraine are particularly at risk of disappearing from these institutions or being abandoned in them. As a result, these institutions can be considered as one of the sources for victims taken by human trafficking and act as central components in child trafficking flows.

“Children in orphanages and crisis centres continue to be particularly vulnerable to trafficking within Ukraine”

Disability Rights International (DRI) highlighted that most countries are downsizing these institutions to move toward more sustainable solutions such as family and community-based care as per the United Nations Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children.12 However, Ukraine has rebuilt most of its institutions. Moreover, international donors may be inadvertently contributing to the support of a system that segregates children due to an ill-informed international response to the crisis in Ukraine. This results in money being poured into these institutions and building more, which are putting children at a higher risk of human trafficking.13 This untargeted aid to help children may reinforce existing harmful practices, which can lead to the proliferation of this institutional system and offers opportunities for criminal networks to exploit children for financial gain. As a result, financial institutions (FIs) may play a crucial role in dismantling a misguided industry that, at best, exploits well-intentioned international donors whilst perpetuating an outdated model of care that fuels child trafficking and acts as the central component in child trafficking flows.

Institution-related Trafficking: Operational Structures

DRI expressed concerns about institutions in Ukraine being used as a recruitment tool for criminal networks and for enabling traffickers to find vulnerable children to exploit. This is based on a three-year investigation of human rights violations perpetrated against approximately 100,000 Ukrainian children segregated from society in these institutions.14 This aligns with the previous observations of the US Department of State in the Trafficking in Persons Report 2011, which states that “homeless children or children in orphanages continued to be particularly vulnerable to trafficking in Ukraine.”15 Anti-trafficking organisations and former residents of institutions reported to DRI that children are systematically trafficked within or outside of these institutions for various forms of exploitation. In this regard, the term “institution-related trafficking” refers to the manifestations of human trafficking in the context of institutional care for children. The four specific cycles of trafficking linked to institutions, according to the Lumos Foundation, include trafficking into institutions, also referred to as “orphanage” trafficking, trafficking out of institutions, victims of child trafficking being placed in institutions and trafficking of care leavers.16

Trafficking Into Institutions

Orphanage Trafficking

Orphanage trafficking refers to the recruitment of children into institutions for exploitation and financial gain. These institutions are seen as doing good and provide a perfect cover for criminal networks, which use various tactics such as deception, coercion and violence to ensure a pipeline of children into these institutions. Orphanage managers may exploit the parents’ social and economic disparity by paying “child finders” to persuade parents into placing or selling their children into orphanages with false promises of opportunities for the children and families. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out that children can also be placed in orphanages because of disability or poverty, or because their parents are considered unfit to keep them. Once in these institutions, children can be subjected to various forms of exploitation to generate financial profit.

Paper Orphaning

Orphanage trafficking typically involves the false construction of children’s identity as orphans. This practice is known as “paper orphaning” and can include the forgery of identity documents, falsification of parental death certificates, production of birth certificates and creation of paperwork attesting to abandonment or relinquishment. In other instances, children can be coached to pose as orphans in the presence of volunteers and visitors.

Trafficking Out of Institutions

Children are easy targets for traffickers seeking to exploit them for financial gain

Children can be trafficked out of institutions into other forms of exploitation. Traffickers are aware of the children’s vulnerabilities and the lack of emotional support they may experience in these institutions. As a result, children are easy targets for traffickers seeking to exploit them for financial gain. Traffickers are known to approach them directly inside these institutions through manipulative techniques such as grooming and capitalising on a child’s wish to run away. The Lumos Foundation also pointed out that children living in residential institutions have a higher chance of going missing and facing a serious risk of exploitation. In some instances, the institutions themselves can be complicit and directly involved in the trafficking.

Inappropriate Funding May Exacerbate Institution-related Trafficking

In times of conflict or disaster, financial support for institutions like orphanages is a popular response for international donors wanting to contribute to relief efforts. However, funding as an emergency response also creates a market for institutions. This emergency response of private philanthropy leads to the proliferation of these institutions. According to the Lumos Foundation: “The sheer size and fragmented nature of donations that can flow into a country following a humanitarian crisis—from individuals and organisations such as faith-based groups, charitable foundations and businesses—can lead to a lack of official oversight of allocation. This creates an ideal environment for unscrupulous individuals and criminal groups to profit from the establishment of bogus orphanages and can undermine national efforts to support broader child protection and social welfare systems.”17

Orphanage trafficking refers to the recruitment of children into institutions for exploitation and financial gain

This variety of short-term thinking leads donors to contribute substantial financial resources to relief efforts, which may harm the children they aim to support. For example, the Lumos Foundation estimates that support to Haitian orphanages exceeds 100 million dollars annually. However, it does not result in quality care and well-being for the children. In a study conducted on the foreign donor support to children in Haitian orphanages, the Lumos Foundation highlighted that more than 80% of the 30,000 children living in these orphanages are not orphans and that “only 15 percent of Haitian orphanages are officially registered with the government. At least 140 are believed to have extremely detrimental living conditions where children are at severe risk of violence, exploitation, abuse, neglect, and avoidable death.”18 In the same regard, Ukrainian institutions visited by DRI have been significantly renovated or refurbished as a result of local and international funding. DRI stated that funding had not brought an end to serious human rights violations, such as human trafficking, within these institutions. Moreover, “by directing financial and professional resources to an outmoded and segregated service system, these new investments leave inadequate resources to promote community integration.”19 According to DRI, the Ukrainian government has promised to bring an end to its system of orphanages, though no efforts have been made to develop family and community-based alternatives that would downsize orphanages and reduce new placements of children in these harmful institutions. In addition, the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action emphasised that in situations of crisis, these institutions “should only be a last resort for the shortest possible period when all family-based interim care options have been explored, are not possible or are not available.”20

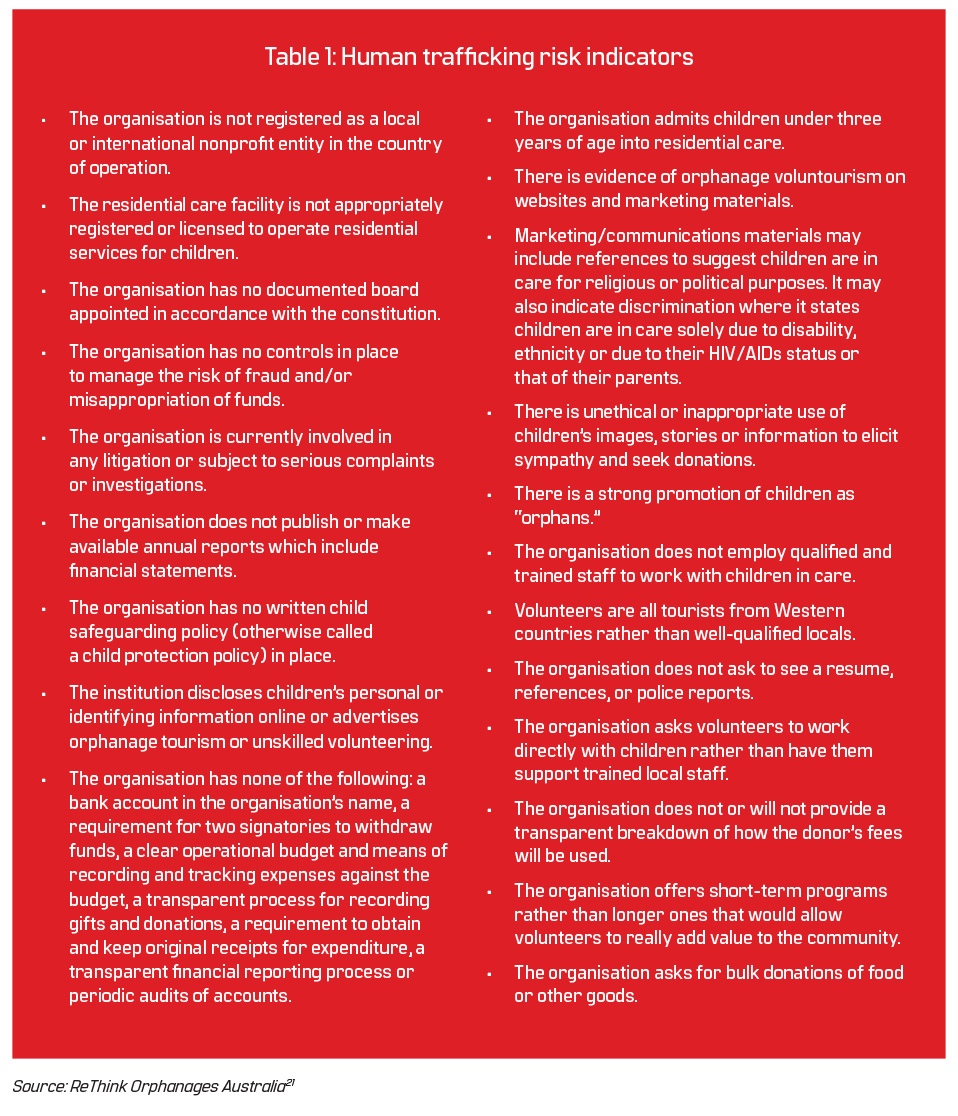

The following table lists several indicators for organisations that might be involved with child trafficking.

The Role of the Financial Sector

Based on the significant number of children placed in institutions worldwide, it is possible that billions of dollars are going into orphanages around the world. ReThink Orphanages estimates that the orphanage voluntourism industry has grown in recent years to an estimated value of 2.6 billion dollars and involves 1.6 million people each year. The funding pouring into these institutions and the global international demand lead to an increase in the number of institutions worldwide.22 The institutions may be run as profit-making enterprises based on the financial exploitation of children. In the worst cases, these institutions may have been set up solely as commercial fronts by organised criminal groups and disguised as legitimate childcare facilities to generate a financial gain. It is difficult to assess the total amount generated by institution-related trafficking. This can be attributed to a lack of awareness in the general public and private sector, a lack of transparency and oversight, and this form of exploitation is not recognised through criminal laws in contrast to labour and sexual exploitation.

Furthermore, institution-related trafficking has strong links to various forms of human trafficking involving organised criminal groups laundering proceeds from diverse criminal enterprises. As a result, international donors and consequently the financial sector may unwittingly contribute to the trafficking of children into or out of these institutions and bear responsibility for funding a system that leaves children particularly exposed to these forms of exploitation and abuse. It is therefore crucial for FIs to conduct thorough due diligence in order to ensure that financial support is not going toward the profiteering of traffickers and organised criminal groups. Ultimately, the financial sector has the potential to disrupt a system that enables the exploitation of vulnerable children for financial gain, especially those in conflict-stricken countries such as Ukraine.

Jonathan Dupont, analyst, financial intelligence unit, independent researcher, Human Trafficking and Child Exploitation, Lithuania, jonathandupont@protonmail.com

- “7.1 Million People Displaced by the War in Ukraine: IOM Survey,” International Organisation for Migration, 5 April 2022, https://www.iom.int/news/71-million-people-displaced-war-ukraine-iom-survey

- “More than half of Ukraine’s children displaced after one month of war,” UNICEF, 24 March 2022, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-half-ukraines-children-displaced-after-one-month-war

- “One month of war leaves more than half of Ukraine’s children displaced,” United Nations, 24 March 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1114592

- “Trafficking in Persons Report 2014,” U.S. Department of State, 2014, https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2014/226841.htm

- “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum,” European Commission, 23 September 2020, p.7, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/1_en_act_part1_v7_1.pdf

- “Children in Institutions: The Global Picture,” Lumos, 1 March 2017, https://www.wearelumos.org/resources/children-institutions-global-picture/

- “Keeping children out of harmful institutions – Why we should be investing in family-based care,” Save the Children, 2009, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/keeping-children-out-harmful-institutions-why-we-should-be-investing-family-based-care/

- “Guidance for protecting displaced and refugee children in and outside of Ukraine,” UNICEF, 10 March 2022, https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/guidance-protecting-displaced-children-ukraine

- “Commissioner Johansson’s speech on the developing situation regarding refugees as a consequence of Russian aggression against Ukraine,” European Commission, 8 March 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/johansson/announcements/commissioner-johanssons-speech-developing-situation-regarding-refugees-consequence-russian_en

- “Trafficking in Persons Report 2014,” U.S. Department of State, 2014, https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2014/226841.htm

- “UNGA 2019 Resolution on the Rights of the Child,” Save the Children, 2019, p. 8, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/unga-2019-resolution-rights-child/#:~:text=This%20resolution%20was%20adopted%20by,children%20to%20have%20a%20family,

- “United Nations Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children,” Save the Children, 2010, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/united-nations-guidelines-alternative-care-children/

- “Ukraine Orphanages Feeder for Child Trafficking,” HuffPost, 2 June 2015, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ukraine-orphanages-feeder_b_7344882

- “No Way Home, The Exploitation and Abuse of Children in Ukraine’s Orphanages,” Disability Rights International, 2015, p.4, https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/no-way-home-exploitation-and-abuse-children-ukraines-orphanages

- “Trafficking in Persons Report 2014,” U.S. Department of State, 2011, p.366, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/eoir/legacy/2014/01/10/TIP_report_2011.pdf

- “Cycles of Exploitation: The Links Between Children’s Institutions and Human Trafficking, A Global Thematic Review,” Lumos, p. 45, https://lumos.contentfiles.net/media/documents/document/2021/12/LUMOS_Cycles_of_exploitation.pdf

- Ibid, p. 80.

- “Funding Haitian Orphanages at the Cost of Children’s Rights,” Lumos, 9 October 2017, p. 6,https://www.wearelumos.org/resources/funding-haitian-orphanages-cost-childrens-rights/

- Ibid., p. 42.

- “Minimum Standards for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action,” The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, 2019, p. 210, https://alliancecpha.org/en/CPMS_home

- “Partnership Due Diligence Assessment Tool, Residential Care Service Providers,” ReThink Orphanages Australia, https://acfid.asn.au/sites/site.acfid/files/resource_document/Rethink-Partnership-due-diligence-final2.pdf

- “Orphanage trafficking,” Parliament of Australia, https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/ModernSlavery/Final_report/section?id=committees%2Freportjnt%2F024102%2F25036#footnote20target