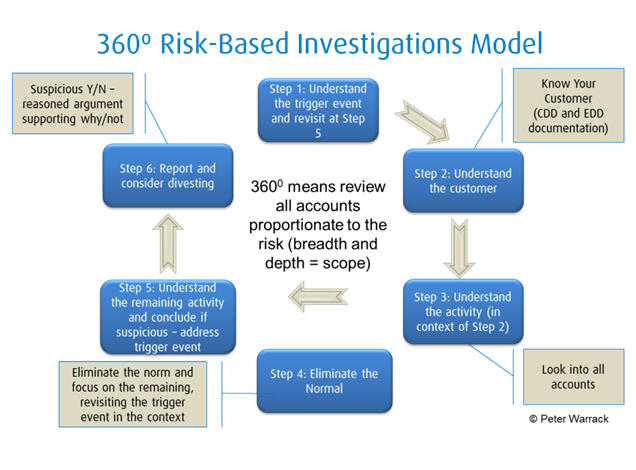

The six step 360 Degree Risk-Based Investigations Model provides consistency of approach and applies critical thinking thought processes by anti-money laundering (AML) investigators conducting their investigations to determine if the transactional activity (or attempted activity) under review is suspicious or not.

The determination or conclusion is in the context of suspecting (based on reasonable grounds to suspect) if the activity or attempt relates to the commission of a money laundering (ML) or terrorist financing (TF) offense and whether or not it is reportable.

The model aligns with the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada’s (FINTRAC) guidance on considering transactions in context, and it was first published in ACAMS Today.1

The model uses a holistic approach in reviewing all of the customer’s accounts in a 360-degree view, but only to the breadth, depth and extent necessary to address the risk that the accounts are used for ML or TF.

Breadth means to the extent of other connected customer relationships and depth means the look-back period, which is aligned to AML financial intelligence unit procedures.

Breadth + Depth = Investigation Scope

Step One: Trigger Event

The trigger event is generally a suspicious activity report (SAR) and a suspicious transaction report or a transaction monitoring alert; in other circumstances it may include an adverse media alert or a law enforcement referral.

The trigger event is what brings the investigation before the eyes of the investigator and it will contain information as to why the matter is considered unusual.

SARs are generally more informative than alerts as they contain information about what the submitter has observed or their opinion.

Transaction monitoring alerts are prescriptive. In other words, the reason for the alert is due to the thresholds and logic of the particular transaction monitoring scenario, or multiple scenarios, (e.g., more than two wires in a 30-day period totaling over $5,000) or in the case of a smurfing scenario, multiple cash deposits below the reporting threshold of $10,000 in multiple branches within a short time frame.

It is crucial that investigators understand the trigger, but the trigger should not result in a myopic and subjectively biased approach to the investigation, which must be conducted objectively. Therefore, the trigger should be parked in memory and revisited when adjudicating the investigation in step five of the model.

Findings regarding the trigger event must be specifically addressed in the investigation adjudication notes (i.e., why was the activity found to be suspicious or why was it not?).

Step Two: Understand the Customer

This is arguably the most important step in the model as it provides the foundational context against which the activity (or attempt) is assessed, evaluated and understood. By completing this step, the investigator should have a good idea of the account activity they should expect to see in steps three through five.

Step two is aligned to the AML Thinking Map, a tool designed to prompt thought to ensure an investigator has covered all of the relevant bases.

Understanding the customer includes, but is not limited to:

- Who they are (i.e., their identity and cultural background, if applicable) and their risk status (e.g., politically exposed persons [PEPs])

- What they do (i.e., occupation, profession or business) and the nature of risk associated to their occupation, profession or business

- How they derive their income and wealth

- What products they hold and why (e.g., requirement for wires, remote deposit capture, etc.)

- Geographic footprint and operating environment (i.e., national/international risk ratings of countries the customer interacts with)

- Relevant adverse information associated with the customer or their business, close associates or family

- Non-adverse information that supports our understanding of the customer

Existing customer due diligence and enhanced due diligence information is obtained from institutional records and from hard copy records held locally at the branch level or by account and relationship managers.

The internet, Open Source Intelligence and other database research provides supporting information.

Step Three: Understand the Activity

Under this step a holistic and high level view of the activity for the relevant review period is undertaken to determine whether the activity in the accounts (all of the accounts) appears to be in line with your understanding of the customer (in step two), their business or occupation.

Completing this step aligns to using a risk-based approach to focus your investigative efforts (in step four) on the unusual/suspicious (i.e., high-risk ML/TF areas).

Step Four: Eliminate the Norm

In alignment with the previous steps, the activity in all of the accounts under review that clearly is commensurate with what would be expected (normal) by the customer is neither considered unusual or suspicious (from an ML, TF or sanctions perspective) and it is filtered out to enable the investigator to focus on the remaining activity.

In the context of a personal account, examples of normal activity might include grocery purchases, rent or mortgage payments, utilities and personal spending commensurate with the customer’s income, payroll and wealth.

Business account examples of normal activity might include payroll, payments/receipts to or from legitimate suppliers commensurate with the business, other overheads (e.g., rent, utilities, reasonable legal and accountancy expenses, IT and marketing, shipping costs, tax payments, fuel, etc.).

Note: In conducting this step, cognizance should also be taken as to the suitability of and the requirement for a customer to utilize certain products (e.g., wires).

Step Five: Understanding the Remaining Activity to Conclude if it is Suspicious or Not

Any activity remaining, if not previously eliminated as normal (i.e., commensurate with your understanding of the customer, including the need for products and the nature of their business), now becomes the focus of your AML/counter-terrorist financing investigation and also includes being alert to potential sanctions violations.

It also includes revisiting the trigger event and incorporating this into your analysis, thinking and conclusion.

Note: If the trigger was reported as attempted activity and in step three the attempted activity could not be understood and eliminated, the attempt should be included in step four. FINTRAC Guideline 2 states:

“Transactions, whether completed or attempted, may give rise to reasonable grounds to suspect that they are related to money laundering or terrorist activity financing regardless of the sum of money involved. There is no monetary threshold for reporting a suspicious transaction.

A suspicious transaction may involve several factors that on their own may seem insignificant, but taken together may raise suspicion that the transaction is related to the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offence, a terrorist activity financing offence, or both.

As a general guide; a transaction may be connected to money laundering or terrorist activity financing when you think that it (or a group of transactions) raises questions or gives rise to discomfort, apprehension, or mistrust.

An assessment of suspicion should be based on a reasonable evaluation of relevant factors, including the knowledge of the customer's business, financial history, background, and behaviour. Remember that behaviour is suspicious, not people.

It could be the consideration of many factors, (not just one factor), that will lead an investigator to a conclusion that there are reasonable grounds to suspect that a transaction is related to the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offence, a terrorist activity financing offence, or both. All relevant circumstances surrounding a transaction should be reviewed and considered.”2

In concluding if the activity (or attempted activity) under review is suspicious, an investigator must use their knowledge and experience and known indicators of money laundering and/or terrorist financing.

Establish the Predicate Offense (Where Possible)

A useful place to start is to seek information pertaining to the commission of a predicate offense. For example, relevant adverse media might inform that the customer has been accused, charged or convicted of fraud, drug trafficking, human trafficking or tax evasion.

If a predicate offense can be established, any movement of the funds thereafter with the intention to disguise or conceal those funds is by definition, money laundering and therefore reportable.

If the predicate offense cannot be identified, then the remaining investigation will be focused on the money laundering aspect and may be reliant on the use of indicators (also known as red flags) in helping an investigator conclude (based on the low threshold of reasonable grounds to suspect) if money laundering (the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offense) or terrorist financing is suspected.

Using Indicators

Indicators can point strongly to money laundering or terrorist financing, but investigators must be cautious about reporting something that is purely based on the presence of indicators (i.e., defensive filing without any further accompanying and articulated analysis as to why the reported activity is considered to be suspicious).

In utilizing indicators, FINTRAC advises:

- “A single indicator is not necessarily indicative of reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering or terrorist financing activity. However, if a number of indicators are present during a transaction or a series of transactions, then you might want to take a closer look at other factors prior to making the determination as to whether the transaction must be reported.

- Indicators have to be assessed within the context in which the transaction occurrs or is attempted.

- Each indicator may contribute to a conclusion that there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the transaction is related to the commission or attempted commission of money laundering offence or a terrorist activity financing offence. However, it may also offer no indication of this in light of factors such as the client’s occupation, business, financial history and past investment pattern.

- Taken together, the presence of one or more indicators as well as your knowledge of your client’s business or financial affairs may help you identify suspicious transactions.”3

Step Six: Report and Consider Divesting

This step simply means to submit the SAR/STR, but to also consider divesting the relationship if the risk of maintaining is outside of an organization’s risk appetite.

AML Thinking Map

Customer Identity and Verification

- Do we know who the customer is, as opposed to who they purport to be?

- How long has the customer relationship been established?

- How is their individual or corporate identity confirmed?

- Is their individual or corporate identity supported by authentic and appropriate documentation or other sources?

- What reliance can be placed on supporting documents or information?

- Does the information provided by the customer correspond with our findings?

- Is the customer included on any sanctions lists or negative databases? Is there relevant adverse information?

- Does it all make sense?

Customer Occupation or Business Activity

- What does the customer do? How do they earn their living?

- What is the nature of risk associated with their declared occupation?

- Is the occupation or activity legitimate and/or within bank policy?

- How is the customer’s occupation verified?

- Is the customer’s income consistent with their occupation?

- What evidence exists to support the income?

- What reliance can be placed on this evidence and how can it be tested and confirmed?

- Does the information provided by the customer correspond with our findings?

- Does it all make sense?

Source of Funds

- What is the source of funds under review? Do we know?

- What is the source of funds used to open the account?

- What evidence exists to support these sources of funds?

- How much reliance can be placed on this evidence and how can it be further confirmed?

- Is the source legitimate and consistent with the customer profile? (Consider evidence of predicate offenses).

- Is the source in itself high risk (i.e., by the industry or country?) Are there any associated sanctions risks (i.e., PEPs, diamonds from Liberia/Iran, etc.)?

- Is the source within bank policy?

- Is the customer entitled to these funds?

- Does it all make sense?

Destination of Funds

- What is the destination of funds transacted? Do we know?

- Who is the beneficiary?

- Who is the ultimate beneficiary? Do we know?

- What evidence exists to support the above?

- How much reliance can be placed on this evidence? How can it be further confirmed?

- Is the destination in itself high risk (i.e., by the industry or country)? Are there any associated sanctions risks (i.e., PEPs, diamonds from Liberia, etc.)?

- Is the destination within bank policy?

- Is the beneficiary entitled to these funds?

- Does it all make sense?

Product and Transaction Type (Types of Funds)

- Is the type of product consistent with the customer’s profile?

- Why is the customer using this product (i.e., drafts and not wires etc.)?

- What is the risk associated with the product?

- Nature of the transactions (volume, amounts, locations, use of other financial mediums, etc.)

- Are the transactions consistent with the customer profile and declared activity?

- Does it all make sense?

Note: The information contained in this article is the opinion of the author and does not reflect the policies, procedures, or opinions of the author’s employer or associations of which he is a member.

- Peter Warrack, “Checklist vs. Methodology: Leveraging the Tenets of EDD in AML Investigations,” ACAMS Today, December 2011-February 2012, http://www.acamstoday.org/leveraging-tenets-of-edd-in-aml-investigations/

- “Guideline 2: Suspicious Transactions,” FINTRAC, July 2016, http://www.fintrac-canafe.gc.ca/publications/guide/Guide2/2-eng.asp

- Ibid.

Great Article Peter. Thanks.