Editor's note: This is the last of a two-part series. Part two will discuss the position of the AML/CTF regimes in each country in Central Asia.

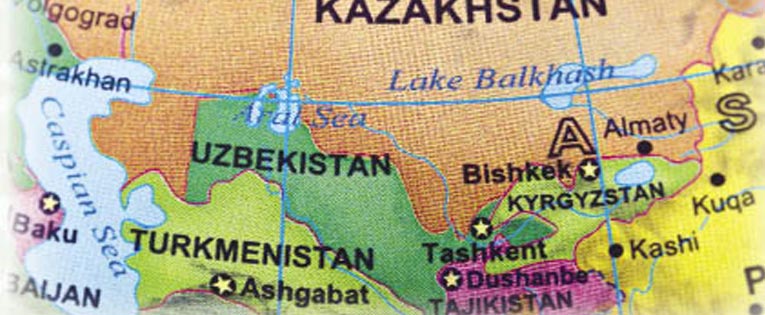

Although critics say that the region still has a long way to go in effectively implementing AML/CTF regimes, the achievements made with the support of the international community during the past two years have been noteworthy. The article also highlights the measures that have been taken by the region's governments to ratify conventions to combat crime and corruption and outlines the milestones, which have been met in setting up a criminal justice infrastructure, in particular vis-à-vis the implementation of AML and CTF regimes.

Central Asia and AML

Crime researchers focusing on Central Asia, and in particular on AML regimes, have in the past criticized some of the governments of adopting a selective approach to implementing AML/CTF legislation and other financial crime regulations, as well as for having politically instrumentalized the AML regime. For example, on several occasions, opponents of the sitting government have faced charges of money laundering or other economic crimes against the political opposition.

Over the past two years, however, significant improvement appears to have been made. Since 2008, all five Central Asian states have ratified the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, and the United Nations Convention against Corruption. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan who were on the Financial Action Task Force's (FATF's) 'black list' have succeeded through a series of technical and financial measures, supported by the international community, to see their names removed from the list.

It is also worth noting that, according to the 2011 International Narcotics Strategy Report 1, none of the Central Asian states are considered to be major money laundering countries. They are not listed amongst the 'Jurisdictions of Primary Concern', meaning that their financial institutions are not seen to engage in transactions involving significant amounts of proceeds from serious crime.

The following section presents some details regarding the criminal situation and the development of the AML/CTF regimes in the five Central Asian states. The presentation does not aim to be comprehensive, but to present some of the key aspects identified by the FATF and various UN bodies and other international organizations that have undertaken in-depth research projects and provided technical assistance projects within the region.

According to the UNODC report, analysis of money laundering activities in Central Asia suggest that there are three main ways in which the proceeds of organized crime are laundered: expenditure on operational costs and reinvestment in further criminal activities; consumption; and investment, mainly through the banking sector.

- Operational costs and reinvestment include: the purchase of fresh consignments of goods, communication devices and vehicles, the establishment of safe houses or hideouts, the payment of bribes to public officials and law enforcement personnel, and the payment of salaries to the members of the organization itself.

- Consumption covers the purchase of real estate (houses and apartments) and luxury items, as well as meetings, banquets and sex services. This kind of money laundering is often cash-based and thus leaves no traces in bank records. Furthermore, according to the 2002 Kyrgyz assessment, criminals do not always have to use special techniques to disguise the source of their illegal gains if corrupt state officials offer them protection.

- Investment using front companies is one of the most important money-laundering techniques in Central Asia. These companies provide ostensibly legitimate sources of income and opportunities for trade-related laundering through false invoicing. In order to open front companies, organized criminal groups in Kazakhstan have targeted banks, casinos and businesses engaged in food processing, distilling and export trade. Casinos are particularly useful for money laundering and there is some concern about their exploitation in both the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan. Reportedly, front companies have also been widely used in the Kyrgyz Republic, where it is believed that illicit revenues from trading in drugs and weapons and the smuggling of alcohol and tobacco are typically transferred to front companies.

- Banking systems in Central Asia, with the exception of the one in Kazakhstan, are not well developed and therefore do not offer many opportunities for money-laundering. However, a commensurate level of controls has not matched even the limited level of development. Although there are some provisions in national laws for dealing with criminal assets and some internal controls in banks, very little attention has been paid to preventing money laundering through the banking system. Inadequate financial controls within the banking sector continue to make detection of money laundering difficult. Also, bank examiners have not traditionally been trained to look for evidence of money laundering, but rather focus on traditional safety and soundness concerns, and law-enforcement agencies have little expertise in following money trails or dealing with the complexities of money laundering. Although some steps have been taken to close both the regulatory and the enforcement gaps, the process is slow and incremental. Therefore, and since developing the kind of expertise necessary to combat money laundering is a long-term process, the 2007 UNODC report summarized by stating that the banking systems in the region will remain vulnerable to exploitation for some years.

Kazakhstan

The 2007 UNODC Report on Transnational Organized Crime in Central Asia noted that the Kazakh business and banking sectors play a multifaceted role with regard to organized crime in Central Asia, in particular, concerning corruption and money laundering. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) conducted a survey in 69 countries of 3,600 business people, which revealed that approximately two thirds of those interviewed perceived that it was necessary to pay irregular fees and additional payments to get things done.

According to the UNODC report, organized crime has allegedly infiltrated the business sector whereby the Mafia reportedly exercised control over 35,000 legal entities including 400 banks, 47 stock exchanges, and 1,500 state enterprises. According to the EBRD research on organized crime in Kazakhstan, experts from business circles, leaders and members of organized criminal groups, explained that at present almost all banks and related financial structures were owned by famous oligarchs and supported by public authorities, intelligence services and law-enforcement agencies.

The same UNODC report also noted that in Kazakhstan, where there are still bank secrecy provisions and where there are an estimated 200 organized criminal groups with links to criminal organizations in the United States and Europe, particular concern centers on money-laundering and illegal financial transactions in the energy sector. The UNODC Global Programme against Money-Laundering has reported that the practice of 'oil swaps', in which traders exchange title to oil in different locations, could be used to obfuscate ownership and payments, thereby facilitating money laundering. In addition, trade-based money laundering could be accomplished through "oil transfer pricing," where shipments of oil are under-invoiced. A method to transfer money out of the country without using the banking sector (i.e., cash smuggling, is common at Kazakhstan's borders).

In September 2010 Swiss prosecutors reportedly launched a criminal investigation into Timur Kulibayev, the son-in-law of Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev, as a result of allegations that he had used Swiss banks to launder the proceeds of fraud in his former role as Head of Kazakhstan's state-owned oil industry.2 According to an article published in the independent Kazakhstan Weekly Newspaper Respublika,3 Kulibayev laundered some US$600 million through Swiss banking accounts. Kulibayev allegedly received the money in the form of bribes, as well as income from the misappropriation of oil and gas assets owned by the state of Kazakhstan between 2000 and 2005. During the alleged illegal acts, Kulibayev was an officer in the companies belonging to the State, first as chairman of the board of KazTransOil, and then as vice chairman of KazMunaiGaz.

In an attempt to address some of the inadequacies highlighted by the IMF already in 2004, Kazakhstan most recently updated its AML legislation in March 2010. According to the web site of the law firm Bracewell & Giuliani, Kazakhstan's AML legislation introduced a number of amendments to Kazakhstan's legislation regulating activities of commercial banks, pension funds and other financial institutions operating in Kazakhstan. The legislation not only affects the domestic activities of Kazakh financial institutions, but also their cross-border dealings with foreign counterparts.

Kyrgyz Republic

As noted in the Economist, 4 the Kyrgyz Republic has accomplished a remarkable feat by the standards of Central Asia, since the overthrow of its authoritarian president, Kurmanbek Bakiyev in April 2010. The country approved a new constitution in June 2010, making the Kyrgyz Republic the first parliamentary republic in Central Asia. The first elections were held in October 2010.

According to 24.kg, a Kyrgyz news agency, the Kyrgyz prosecutor general's office filed various criminal cases, since late 2010, against the Bakiyev family and their henchmen who were allegedly involved in the development of corruption schemes involving large-scale embezzlement of public funds.

Although it is the most liberal country in the region, ethnic conflict in the southern region of the country is of concern for the country's stability. Four months after ethnic violence erupted in the southern Kyrgyz Republic, with 2,000 Uzbeks murdered in a series of shadowy state pogroms, Kyrgyz security agencies are continuing to persecute Uzbeks. The Kyrgyz Republic has been praised by the international community for its recent positive developments. Critical voices do, however, continue to persist. The Guardian reported that Uzbeks complain of arbitrary detention, mistreatment in custody, legal abuses and extortion. Pessimists predict that the Kyrgyz Republic, which hosts a U.S. and a Russian airbase, could become a failed state, sucking in drugs, organized crime, Islamic radicalism and other destabilizing influences from Afghanistan and Pakistan.

According to the U.S. Department of State's 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, the Kyrgyz Republic is not a regional financial center. The Kyrgyz banking system remains comparatively underdeveloped. Like other countries in the region, the Kyrgyz Republic's alternative remittance systems are susceptible to money laundering activity or trade-based fraud. Money laundering and terrorist financing primarily occur through trade-based fraud and bulk cash carriers. Narcotics trafficking, the smuggling of consumer goods, tax and tariff evasion, and official corruption continue to be major sources of illegal proceeds within the Kyrgyz Republic.

In late 2009, the Kyrgyz Republic updated its AML legislation to address gaps in preventive measures on customer due diligence, recordkeeping and internal controls. These updates were applied to non-bank financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions. The 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, noted however, that the lack of political will and inter-agency cooperation, resource constraints, inefficient financial systems, and corruption all serve to stifle efforts to effectively combat money laundering and terrorist financing in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Tajikistan

Not only does Tajikistan continue to be an important transit country for drugs en route to Russia and Europe, but according to the International Crisis Group, Tajikistan is on its way to becoming a failed state. Given its lawlessness and its 1,300 km southern border with Afghanistan, observers fear that conflict in Afghanistan might spread, bringing extremism and chaos to Tajikistan.

Regarding the country's involvement and exposure to money laundering, there is reportedly, according to the 2007 UNODC report, evidence that considerable amounts of money (both legitimate capital and proceeds of crime) have been moved out of Tajikistan to accounts in the United Arab Emirates and the Russian Federation. The UNODC report also noted that the banking system and commercial companies could be exploited with little fear of detection. Moreover, the influence of organized crime over the banking sector provides an additional layer of safety for criminals. For the most part, laundered funds do not return to Tajikistan. The portion that does re-enter the Tajik financial system is usually invested in businesses and real estate.

Money laundering and terrorist financing primarily occur through trade-based fraud and bulk cash carriers

According to the U.S. Department of State's 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Tajikistan operates largely on a cash economy. The criminal proceeds laundered in Tajikistan derive primarily from foreign criminal activity related to the large portion of opiates cultivated and refined in Afghanistan traveling to Russia and other former Soviet countries via Tajikistan. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Afghan-based narcotics trafficking organizations are seeking weapons in Tajikistan in exchange for heroin in barter-exchange agreements. These weapons are then provided to the Taliban and Taliban-related organizations to support their efforts against the U.S. led coalition. Domestic goods smuggling also occurs in Tajikistan. The report maintained that Tajikistan has few meaningful money laundering controls and little enforcement.

Radio Free Europe reported that the OSCE representative on freedom of the media has expressed concerns about recent developments limiting media access and increasing pressure on independent media in Tajikistan. Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, raised these concerns in a letter to Tajik Foreign Minister Hamrokhon Zarifi. An OSCE press release said several Tajik and foreign information web sites have been made inaccessible in the country since 29 September 2010. At the same time, tax inspections took place in several independent newspapers and printing houses, following which the printing houses refused to print a number of independent newspapers.

Although Tajikistan has enacted AML and CTF legislation, it does not meet all international standards. There are for example, according to the 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, no KYC rule requirements, no suspicious transaction reporting and no large currency transaction reporting. With regard to Tajikistan's AML regime, UNODC reported that in December 2009 the EAG decided to place Tajikistan under the enhanced follow-up procedure.

In February 2011 Central Asia Online, 5 reported that the Tajik parliament's lower chamber had passed a bill banning money laundering. The bill calls for the establishment of a monitoring system for money transfers, as well as the development of legal mechanisms to prevent the legalization of illegally acquired funds. Furthermore, the article noted that the National Bank had formed a financial department to prevent money laundering.

Turkmentistan

According to the 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Turkmenistan is not an important regional financial center. There are only five international banks and a small, underdeveloped financial sector. Foreign companies operate, but do not own, three hotels and two casinos in Turkmenistan, which under certain conditions could become vulnerable to financial fraud and used for money laundering.

Turkmenistan exports billions of dollars worth of natural gas, relying heavily on a complex network of opaque Russian and Ukrainian energy firms, raising money-laundering concerns. In addition, given Turkmenistan's shared border with Afghanistan, money laundering in the country also involves proceeds from illegal narcotics trafficking and trade, derived primarily from domestic criminal activities.

Until 2010, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were 'black-listed' by the FATF for not meeting international AML/CTF standards. In June 2010 Turkmenistan joined the Eurasian group on combating money laundering and financing of terrorism (EAG). In the same month the FATF moved Turkmenistan to the list of countries 'improving global AML/CTF compliance — ongoing process.' The FATF reported that Turkmenistan has been implementing necessary measures to enhance national AML/CTF legislation and institutional framework. Significant improvements have been made due to the achievement of the newly established financial monitoring department under the Ministry of finance of Turkmenistan (national FIU), which was created in January 2010. In May 2010 Turkmenistan adopted amendments to the Criminal Code (in particular regarding the article on money laundering in compliance with Vienna and Palermo Conventions). An article on terrorist financing was also implemented due to FATF recommendations. The EAG mutual evaluation of Turkmenistan was held in November 2010. The results of the mission will impact the level of confidence in the nation's financial system held by the international community, and the country's investment appeal.6

In April 2011, Central Asia Security Newswire7 reported that the Turkmen president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov had ordered his top officials to set up the conditions necessary for Turkmenistan to join a key Eurasian anti-money laundering and counter terror financing group. Berdimuhamedov signed a presidential decree to establish the necessary conditions.

Uzbekistan

According to the U.S. Department of State 2009 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Uzbekistan is not an important regional financial center and does not have a well-developed financial system. Corruption, narcotics trafficking and smuggling generate the majority of illicit proceeds. In addition, organized crime organizations control the proceeds from narcotics and other criminal activities, such as smuggling of cash, high-value transferable assets (e.g., gold), property and automobiles. Drug traffickers and other organized crime groups also control illicit proceeds in foreign bank accounts. Uzbekistan is home to a significant black market for smuggled goods. The 2011 International Narcotics Strategy Report claims that combating drug trafficking is now one of Uzbekistan's top national priorities in order to protect the country's overall security.

In 2001, the United Nations' common country assessment of Uzbekistan highlighted that 65 percent of foreign firms reported that they had to pay bribes to officials for various government services. According to the 2011 International Narcotics Strategy Report Uzbekistan is focusing on combating corruption and has taken steps to implement an anti-corruption program. Uzbekistan's president also issued a decree on measures to counter corruption. The report further notes that there seems to have been an increased number of public officials arrested and prosecuted for corruption in 2010, though most of these were not law enforcement officials. The report notes that although the increased prosecution for corruption might indicate an increase in political will for dealing with corruption, it is likely that political motivations to expose some public officials to accusations of corruption while keeping others immune from prosecution will prevail.

Following the inaction of AML legislation in 2006, the government of Uzbekistan has taken a series of legal actions to implement an AML/CTF regime, which meets international standards.

In 2006, according to a report published by the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, 8 the government of Uzbekistan suspended the implementation of the law through a series of decrees until 1 January 2013. The Financial Action Task Force subsequently released a statement in which it highlighted the significant vulnerability within the international financial system as a result of the developments in Uzbekistan and reacted by calling for urgent action to address this vulnerability and to meet international standards.

As a result of international pressure, Uzbek authorities filed a request for assistance in late 2008 on the basis of which the International Monetary Fund designed a proposal for a small project comprising basic consultancy in the area of AML/CTF technical assistance. The program is ongoing and financed by the Swiss government.9

Also in 2009, following the introduction of new AML legislation, OSCE launched a two-year project supporting money laundering policies in Uzbekistan. The project aimed to improve the functional capabilities of Uzbek anti-money laundering structures, namely the Financial Intelligence Unit within the Office of the General Prosecutor and the relevant structures within the Central Bank. It provided training, practical assistance and exchange of best practices. Staff responsible for financial investigation received training allowing them to perform their tasks and undertake and co-ordinate complex financial crime investigations. Components of the project were additionally supported by contributions from the German government.

In early 2010, after having been black listed in 2008 and 2009, Uzbekistan was removed from the FATF's 'black list' and is therefore no longer subject to the enhanced monitoring process. In February 2010, FATF welcomed Uzbekistan's significant progress in improving its AML/CTF regime and for having addressed the AML/CTF deficiencies that the FATF had identified in February 2008.10 The country has made significant progress in the installation of a more effective and functioning criminal justice system given that until 2001, the system had no accurate records. Additionally, according to the UN common country assessment of Uzbekistan in 2001, the judges' decisions or opinions were rarely in written form, were never published and not widely available to legal practitioners and the public.

According to EBRD, although some progress has been achieved on the economic side in Uzbekistan since the bank started its program in 2003, there was no improvement in Uzbekistan's political environment and prospects for quick political liberalization remain remote.11

Conclusion

From a geopolitical perspective, in particular Central Asia's proximity to Afghanistan, and the activities of local terrorist groups, the region as a whole remains high risk as it embarks on the slow process of combating crime. Furthermore, the great game being played out in Central Asia by the world's largest powers leave the region fraught with a very insecure and volatile future. Like its neighboring country Afghanistan, Central Asia is culturally, ethnically and politically complex making the region a difficult and sensitive construct with which to operate.

Moreover, the issues of human rights protection in relation to the declared aim of the international community to combat terrorism in the region need careful handling. Although significant improvement has been seen in the Central Asian region in recent years, the region has a long way to go before AML/CTF laws are effectively implemented. The looming terrorist threat coupled with the overall political instability of the region makes the enforcement of AML/CTF regimes more pressing than ever.

- http://www.state.gov/p/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2011/vol2/156373.htm

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/8161362/Kazakh-billionaire-faces-money-laundering-investigation.html

- http://www.respublika-kz.com/news/doslovno/11378/

- http://www.economist.com/node/17258828?story_id=17258828

- http://centralasiaonline.com/cocoon/caii/xhtml/en_GB/newsbriefs/caii/newsbriefs/2011/02/17/newsbrief-11

- http://www.eurasiangroup.org/en/news_pg2.html

- http://centralasianewswire.com/Security/viewstory.aspx?id=399

- http://www.fincen.gov/statutes_regs/guidance/html/fin-2008-a004.html

- http://www.swiss-cooperation.admin.ch/centralasia/en/Home/Activities_in_Uzbekistan/Anti_Money_Laundering

- http://www.fatf-gafi.org/document/39/0,3343,en_32250379_32236879_44650215_1_1_1_1,00.html

- http://www.ebrd.com/pages/country/uzbekistan/key.shtml