Cybercrime for profit is a global economy that causes most of our cybersecurity and fraud woes and it is a problem to which all anti-money laundering (AML) and financial sector professionals should pay close attention. It is adaptable, ingenious and lucrative, while imposing vast costs on us. It victimizes financial institutions and their customers, and it uses our financial system as a conduit to transmit illicit profits and payments. Cybercrime for profit also provides a foundation for many other types of cybercrime, including hacktivism and nation-state attacks.

Cybercrime exploits companies and individuals throughout the world and it is perpetrated from all over the world, victimizing and using financial institutions everywhere. Thus, it is important that the global community works together to fight cybercrime. The U.S. is one country that is a lucrative target and pipeline due to its wealth and robust financial sector.

Crime has existed since the dawn of civilization, but cybercrime presents a defining change. Previously, criminals needed physical proximity to the victim. Now, criminals can victimize institutions and individuals from afar and across international borders. This shift means a global pool of attackers, decreased odds of apprehension, increased profitability and reliance on the financial industry to perpetrate these crimes from afar. Traditionally, law enforcement plays a major role in keeping crime suppressed to a manageable level, but with cybercrime it has not yet gained such traction. All of this demonstrates the important role the financial sector can play in reducing cybercrime.

The immense profitability of cybercrime demonstrates the high cost of victimization and the massive amount of theft, but it also presents an opportunity. Law enforcement and the AML community can “follow the money” among the facilitators and to the ultimate perpetrators. Furthermore, cybercriminals commit these frauds because they make money from them. Thus, finding a way to reduce the flow of the profits would make it less lucrative and it would reduce the size of the criminal economy.

When foreign-based cybercriminals commit cybercrime and fraud that victimizes the U.S., funds representing illicit profits are transmitted through and outside of the U.S. financial system, and into the hands of the cybercriminal. In order to detect and stem this flow, one must understand the cybercrime and identity theft economy (i.e., how the participants earn money and how they pay each other).

The Cybercrime and Identity Theft Economy

One of the first criminal investigations to explore the full nature of this global cybercrime economy was People v. Western Express International, Inc., et al., a case brought against a corrupt digital currency exchanger and some customers who were cybercriminals and identity thieves.1 Underpinning the case were valuable lessons that hold true today and teach us about:

- The relationship between international cybercriminals and domestic identity thieves

- The marketplace for stolen data and the crimes they are used for

- Value transfer methods to support the trafficking of stolen data

- Cybercrime money laundering techniques

- Methods cybercriminals and identity thieves use to achieve anonymity

- Methods to pierce veil of anonymity

Successful identity thieves and cybercriminals are good at what they do, reap considerable profits, maintain anonymity and evade law enforcement. However, this financial success provides evidence of both criminality and identity.

The key to reducing the cybercrime and identity theft economy is understanding it. The economy revolves around the theft of data, its resale and use to commit identity theft. Within the marketplace are many different actors, each performing different roles, all trying to make money. Many successful participants reside internationally, which means they need to rely on the U.S. financial system and U.S. participants to monetize cybercrime.

How Cybercrimes Are Monetized Internationally

Email Account Hacking

Email account hacking is a lucrative cyber fraud against which we should protect ourselves. Criminals might try to monetize a compromised email account through a simple scheme where the hacker sends a blast email to all of the victim’s contacts:

“Help, I’m stranded in [insert foreign city], please wire money ASAP.

Don’t try to call me because I lost my phone.”

A greater threat is criminal use of a hacked email account to cleverly misdirect bank wires and steal the funds—representing an evolution of social engineering skills that has stolen hundreds of millions of dollars. Such scams are termed “business email compromise” fraud, “CEO fraud,” or “CFO fraud,” and every employee in the financial sector must be aware of them. Suppose Company A regularly receives invoices from Company B and then pays by bank wire. A criminal hacks the email account of a Company B employee, impersonates that employee and sends an email to Company A, providing “new” bank wiring instructions. The employee in Company A is fooled and Company A wires funds to the “new” bank account, which is controlled by the fraudster who immediately wires the funds out of the country. The fraud can be quite sophisticated and believable, comes in variations that do not require email account hacking, and the scam can deceive victims to delay detection for days or weeks. This fraud directly affects the conventional financial system as it uses traditional bank accounts and bank wires to steal, launder and send funds out of the country.

Payment Card Fraud

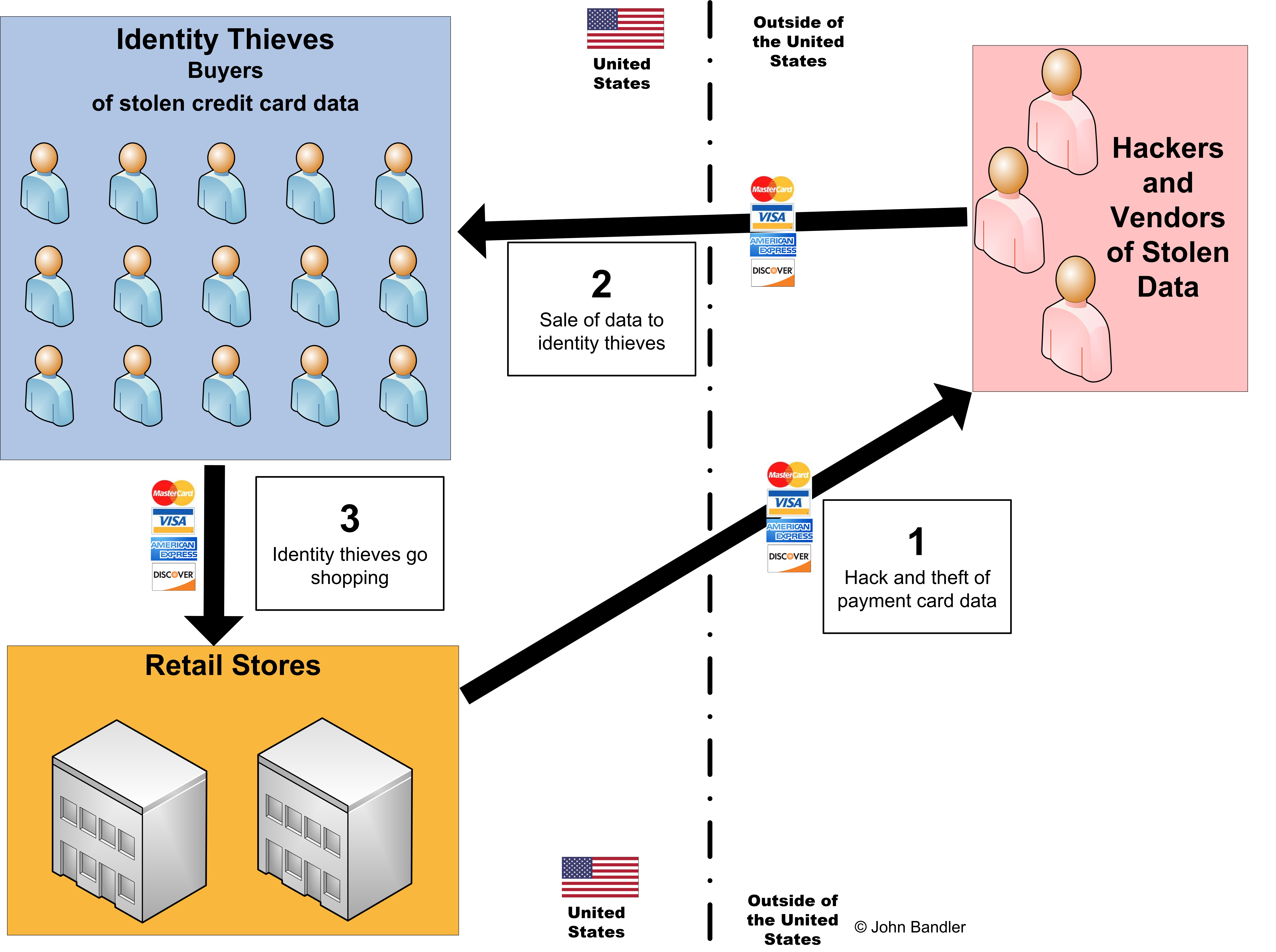

Payment card fraud requires many participants, and each needs to get paid for their part in making the fraud possible. This fraud relies on three basic steps that are depicted in Figure 1:

- The theft of credit card data, such as through the data breach of a retailer

- The sale of this stolen data to identity thieves

- The use of this stolen data to commit fraud

Here, the hacker is located outside of the U.S., and steals data pertaining to millions of credit card accounts from a retailer in the U.S. Stealing this data does not itself earn money for the criminal, so he must sell it to others to make money. Since this data was stolen from the U.S., the best market for this data is identity thieves in the country, since attempting to use these payment cards in foreign countries would likely trigger fraud alerts.

The identity thieves pay for this stolen data in a manner that maintains anonymity, and each payment may be small, a few hundred or thousand dollars. Payment could be sent through a money transfer service while using fictitious sender and recipient names or it could be sent via digital currency, such as Bitcoin, WebMoney and Perfect Money. Through these payments, a single vendor of stolen credit card data could earn millions of dollars per year.

Many other types of cybercrime fraud that exist ultimately require payment or transfer of funds from the U.S. to international cybercriminals based out of the country.

Moving the Money

When sending and receiving payments, criminals—like legitimate business people—try to balance financial cost, convenience, speed and reliability. Criminals have the additional need for anonymity and secrecy. AML professionals should consider four basic conduits that cybercriminals use to move their funds:

- Bank wires through the conventional financial system

- Money transfer services

- Digital currency

- Money mules and shell corporations

Criminals have been misusing the financial system and payment methods since their respective creations. It should be no surprise that cybercriminals continue this trend and misuse whatever is available to them.

Bank Wires

Bank wires, through the conventional financial system, remain an essential part of global funds transfer and are essential to the cybercrime economy. Financial institutions face a triple threat: 1) they are repeatedly attacked and risk becoming a fraud or data breach victim, 2) they need to prevent their customers from becoming fraud victims and 3) they need to prevent themselves from being used as an unwitting conduit for criminal funds or activity.

Bank wires might be initiated or misdirected based on fraud, including through the email account compromise scenario previously discussed. Banks have procedures to detect if the customer has been hacked, but sometimes procedures to detect other frauds are lacking. If the account holder relies on a third party who is hacked, or if the account holder is otherwise deceived or used as a tool for cybercrime-related fraud, banks might fail to detect it. Furthermore, some bank customers may use a variety of techniques to conceal the true ownership, source and destination of funds, including through money mule accounts and shell corporations. Bank wires also play a significant role with digital currency.

Money Transfer Services

Money transfer services, such as Western Union, are an important tool for identity thieves and cybercriminals, because it allows them to pay for stolen data, cybercrime services, and to purchase digital currency. To maintain anonymity, fake names are used when sending and receiving the payments. Successful cybercriminals earning millions of dollars per year may employ the services of other criminals to receive and process these money transfer payments. Occasionally, one recipient name becomes blocked because of associations with criminal conduct, in which case criminals can move on to another recipient name.

Digital Currency

Digital currency has existed for two decades, and cybercriminals and identity thieves embraced it early on. The regulated digital currency industry is just a few years old. Though some digital currency proponents can be sensitive about its linkage with cybercrime, there are synergies that should be acknowledged and understood. They are ignored at the peril of the industry, since understanding makes it possible to keep the digital currency system clean, and thus ensure it is sustainable as a regulated industry.

Digital currency’s connection to crime does not make it unique as a payment method. Consider how cash currency has been intertwined with traditional street crime, as with the drug trade. When illegal drugs are sold, the criminal transactions are in-person, and drugs are exchanged for cash. Successful drug dealers need to integrate mountains of cash into the financial system, and thus developed sophisticated money laundering schemes to make this possible. In contrast, cybercrime and data trafficking criminal transactions are completed online, and cash is inadequate. Payment needs to be made online, instantly and anonymously, in order for the stolen data to be delivered to the purchaser. Digital currency can do that; thus, it merely does for the cybercrime economy what cash does for the illegal drug economy. Compared to cash, there are both benefits and drawbacks for AML and law enforcement professionals.

Digital currency is affiliated with conventional banking and bank wires. Every digital currency exchanger needs a conventional bank account, and international bank wires are necessary to transmit funds in order to equalize the inherent trade imbalance that occurs when the cybercrime economy uses digital currency.

This digital currency trade imbalance occurs because there are identity thieves within the U.S. who continually purchase digital currency, which is then used to pay international cybercriminals for stolen data. This creates a continual flow of digital currency payments from the U.S. to the destination country, and this digital currency needs to eventually be “repatriated” back to the U.S., so that it can be reused.

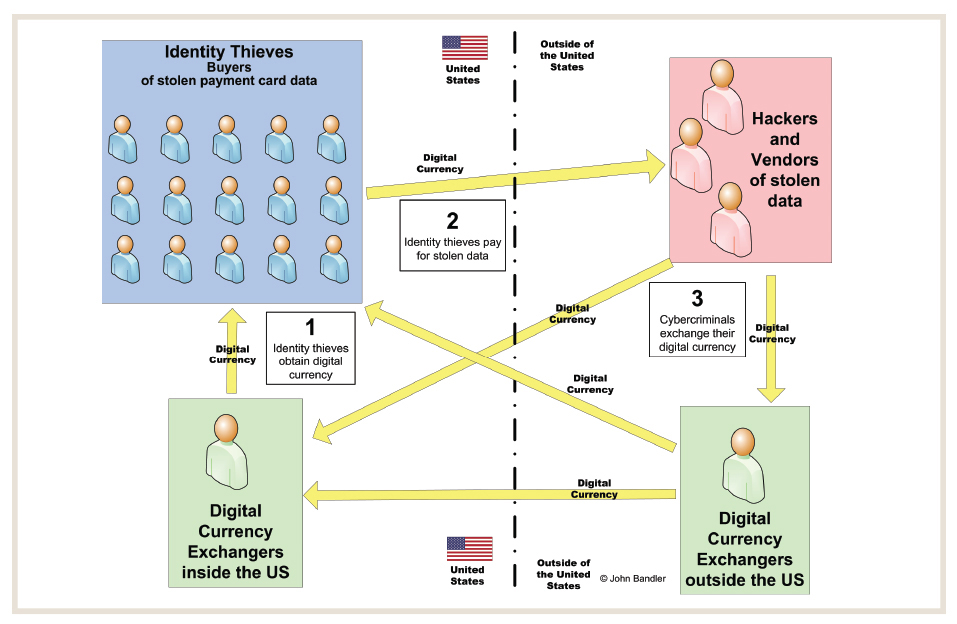

Consider Figure 2 and the basic steps depicted:

- Identity thief obtains digital currency

- Identity thief pays cybercriminal for stolen data

- Cybercriminal exchanges digital currency for fiat currency

- Repeat — identity thief needs more digital currency to buy more stolen data

The individual digital currency payments may be hundreds or thousands of dollars. In the aggregate, this represents an annual flow of millions of dollars.

Also, consider ransomware, an unchecked and lucrative fraud that also relies on digital currency, earning international cybercriminals millions of dollars per year. Ransomware is malware that infects a user’s computer and then encrypts the user’s data and holds it hostage, unless and until payment is made by digital currency from the victim to the fraudster. Thousands of ransomware victims purchase digital currency, which they then pay to international cybercriminals.

All of these digital currency payments to international cybercriminals create a digital currency trade imbalance, which is cured through repatriation of this digital currency back to the U.S. This return of digital currency can be accomplished through aggregate transactions of digital currency, with reciprocal bank wires from U.S. accounts to international accounts in order to pay for this digital currency.

Money Mules and Shell Corporations

Cybercriminals located internationally rely on institutions within the U.S. to receive and process payments. Where funds are stolen from victims in the U.S., and ultimately destined for cybercriminals overseas, a money mule provides a convenient waystation through which to deliver the funds. A money mule is essentially a witting or unwitting person who receives and then transmits illegally acquired funds.

Consider the email account compromise scam previously mentioned, where Company A thinks it is wiring funds to Company B’s “new” bank account, but instead is wiring it to a money mule account, under the control of the fraudster. Company A is fooled by this fraud because the money mule’s account is within the U.S. If Company A had been told to wire the funds internationally, they would have known it was a fraud, because Company B would not use a foreign bank account. Thus, the domestic money mule account is required to receive the funds, which can then be wired internationally. By the time the fraud is detected, the funds are outside of the U.S. and cannot be recovered. There are many ways through which money mules are recruited. Some crude, some quite sophisticated, backstopped with legitimate looking corporate identities, websites and documents.

Though money mules are often “disposable” (used for a single incidence of fraud and then cast away by the cybercriminal), there are more permanent waystations for funds. Shell corporations (or shelf corporations) and their bank accounts require more setup and management, and thus are less disposable. The underlying purpose remains the same: to disguise the true purpose of the account and the true owners. Once fraud or money laundering is detected, it is difficult for regulators and law enforcement to identify the ultimate beneficiaries of the fraud.

Stemming the Flow

Stemming the flow of cybercrime funds requires emphasis in the following areas:

- Personal cybersecurity and fraud awareness

- Increased review and scrutiny by the financial system

- Increased payments scrutiny

Personal Cybersecurity and Fraud Awareness

Every unsuspecting person is an avenue through which criminals can compromise computer or financial systems

Cybersecurity and anti-fraud is not just for experts, but an individual responsibility, like putting on a seatbelt or locking your front door at night. Every unsuspecting person is an avenue through which criminals can compromise computer or financial systems. This starts with each person at home, which protects the individual and family, and then extends to the organization. Each person can transform from being a potential attack victim to a detection sensor.

You should harden yourself by employing basic cybersecurity steps:

- Enable two-factor authentication (two-step login) on financial, email and other important online accounts

- Ensure your computing devices are kept malware free and updated

- Back up your data regularly and store it offline

- Do not open suspicious attachments or click on suspicious links

- Have verbal conversations to confirm any payment instructions

- Use common sense

Increased Review and Scrutiny by the Financial System

The financial system faces the triple threats previously discussed, and is well suited to combat cybercrime funds transfer because of their resident expertise, systems and access to significant datasets. The financial system is ultimately the conduit through which aggregate cybercrime profits exit the U.S., so deeper analysis can help identify that.

Cybercriminals will continue to find victims and money mules within the populace of the U.S., and financial institutions should use their expertise in fraud and money laundering detection to identify these situations and stop illicit funds from exiting the country. Certain countries and banks are more likely to receive cybercrime fraud derived funds, and have proven uncooperative about tracing or recovering stolen funds. Overseas wires to such destinations should be scrutinized carefully before they are sent, because they are not recoverable once they are sent.

Increased Payments Scrutiny

International money transfers for the purpose of purchasing stolen data follow discernable patterns, even when fictitious names are used by the sender and recipient. With enough data and experience, it is possible to distinguish criminal payments from legitimate payments. Similarly, though many digital currency accounts may be anonymous, payments can still be analyzed to discern criminal purposes. Furthermore, patterns indicating repatriation of digital currency to the U.S. should be closely researched.

The advent of digital currency regulation within the U.S. brought know your customer (KYC) requirements to domestic digital currency exchangers, meaning identity thieves may be inclined to use exchangers located outside the country. Thus, international money transfers can be used to purchase digital currency, and those patterns should be analyzed.

KYC methods that rely on telephone or online identity verification have inherent weaknesses when it comes to identity thieves and cybercriminals. These criminals have nearly unlimited access to stolen personal identifiable information, thus the mere provision of pedigree such as name, address, birthdate and social security number may be of limited use to confirm identity. In addition, if a payments company identifies suspicious activity and merely blocks payments to one criminal alias, the criminal will merely establish another. Thus, deeper analysis and a deeper remedy may be required. Finally, the ability of these criminals to make convincing forged identifications must also be considered, whether the identifications are presented online or in person.

Conclusion

Our collective steps as citizens of the world to combat the cybercrime epidemic have not been adequate yet, and there is room for improvement on many fronts. The financial and AML communities should recognize the crucial role they can play in this fight, and should work to reduce the flood of ill-gotten gains that criminals earn from these crimes.

For information on how you can identify where your organization is most vulnerable to a cyber-attack, please visit: http://www.acams.org/cyber-enabled-crime-training/.

- The investigation and prosecution spanned nearly a decade, most defendants pleaded guilty, while three proceeded to trial and were convicted of every count. See, e.g., Kim Zetter, “Ukrainian Carder in $5 Million Ring Sentenced to 14-Plus Years in Prison,” WIRED, August 8, 2013, https://www.wired.com/2013/08/carder-eskalibur-sentenced/.