Fraud can be simply described as the act of deception for personal gain. Acts of deception usually involve victims, either individuals or businesses. In most fraud occurrences, the primary motive and gain is financial. However, data has also become the primary target of fraudulent acts. The various forms of fraud are not limited to mail fraud, identify theft, tax fraud, bank account takeover, romance scams, elderly abuse and cybercrime.1 In the 1950s, criminologist and sociologist Donald R. Cressey developed the fraud triangle theory. The concept demonstrates three elements that are usually present in most, if not all, fraud occurrences:

- Motivation: Fraudsters are usually motivated to obtain funds illegally to lead luxurious lifestyles, compensate for sudden financial loss, support dependency on narcotics or alcohol, or to repay debts/loans.

- Opportunity: The need and the motive encourages the fraudster to search for creative opportunities to carry out acts of fraud against various types of victims.

- Rationalisation: The fraudster psychologically justifies their acts as being performed for legitimate needs or motives to harm others financially.2

Fraud victims are comprised of various backgrounds: racial, gender, age, religious, socioeconomic and educational.3 The perpetrators prey on their victims’ greed or weakness. For example, in the case of romance scams, the perpetrator searches for ways to exploit the victim’s potential loneliness as their weakness. Taking advantage of the emotional vulnerability, the fraudster provides the victim with the illusion of relationship security. This usually precedes the eventual request for funds. Another example can consist of exploiting individuals of certain age groups. Young people can fall victim due to their possible naivety and lack of financial management experience, whilst the elderly may be abused due to possible loneliness, Alzheimer’s or dementia. The perpetrators may also choose to prey on high net worth individuals with significant savings, investments and real estate properties. For the purpose of amassing further wealth, these individuals are also susceptible to being defrauded.

The perpetrators come in various forms, identities and diverse backgrounds. In other words, not all fraudsters have previous criminal records, are uneducated or belong to a particular socioeconomic status. Today’s fraudsters are often highly trained and sophisticated professionals, educated, possibly have wealthy backgrounds and can be located anywhere in the world.

Historical Cases of Fraud

Fraud has existed throughout history and is not a recent occurrence. In what is described as the “greatest scam of all times,” the con man “Count” Victor Lustig from Austria-Hungary, was able to sell the Eiffel Tower of Paris not once, but twice.4 Known for his charisma, charm and knowledge of five languages, Lustig built a criminal reputation from a young age and established himself as one of the greatest con artists of all time.5 After dropping out of the prestigious Sorbonne University in Paris, traveling the world committing various criminal acts under different aliases and being arrested more than 50 times, Lustig committed the “holy grail of scams” in Paris in May 1925.6 He issued a letter inviting the wealthiest businessmen in the metal industry to a meeting where he convinced them of the necessity of demolishing the Eiffel Tower due to engineering errors and expensive maintenance. To maximize his financial gain from this elaborate scheme, Lustig targeted the wealthiest individuals in the scrap metal industry and started a bidding war between them. His eventual victim was André Poisson, who was scammed for a total amount of 350 million dollars. Only a month later Lustig repeated the scam.7 Lustig was so proud of his repeated accomplishments in fraud that he developed the list of 10 commandments for swindlers.8

The 10 Commandments for Swindlers

- Listen patiently instead of talking fast

- Never look bored

- Agree with political opinions

- Agree with religious views

- Flirt, but do not follow up unless the other party initiates the first move

- Never discuss illness

- Never pry

- Never boast

- Never be untidy

- Never get drunk

Another successful scam of his was the “Rumanian Box.”9 In this scam, Lusting used a small box he built with cranks and knobs attached and a slot where bills were placed. Lusting would prey on his target by obtaining a 1,000 dollar bill from the victim and placing it in the box slot before turning the cranks and knobs. Lusting’s stipulation to his victim was that it would take up to six hours for another genuine 1,000 dollars to appear out of the other end of the box. He would then authenticate the bill with the victim, thus gaining their trust. Lusting would then offer the victim the opportunity to purchase the box for a significant amount. The six-hour rule provided Lustig with enough time to flee the scene before the victim discovered that the box was a scam and did not, in fact, generate any new bills.

Greed eventually got the best of Lustig after an unsuccessful operation to counterfeit bank-notes, which threatened the confidence in the American economy. He was captured in 1935 and was sentenced to 20 years in maximum-security federal prison.

Recent Fraud Occurrences

In recent years, synthetic identity fraud is emerging as a new trend in which fraudsters rely on identity theft to open fake bank accounts.10 The rapid increase in the digitisation of banking services, such as mobile banking, has accelerated this trend. After the COVID-19 pandemic, fraudsters began targeting health organisations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as well as the World Health Organization to steal sensitive personal data, which facilitates perpetuating crime due to the ease in creating false identities.11

With the rise of online dating, even romance scams are becoming digitised and taking place online

With the rise of online dating, even romance scams are becoming digitised and taking place online. This usually occurs when the perpetrator adopts an online identity using false personal information and photos to gain the victim’s trust and affection.12 The vulnerabilities being exploited in targeted individual are usually loneliness and the need for a relationship. Romance scam con artists usually claim that they work in the construction industry and reside outside of the victim’s particular jurisdiction to avoid the need to meet in person. Upon gaining the trust and affection of the victim and establishing marriage/relationship plans, the perpetrator will eventually ask for money due to unforeseen circumstances or a medical emergency due to an accident.13 Given their false identity and likely being outside of the victim’s jurisdiction, it becomes very difficult to trace these fraudsters after stealing the money.

Imposter scams also increased significantly since 2020 and following the pandemic.14 Imposter or impersonation scams usually occur when perpetrators impersonate legitimate entities to swindle victims out of their money. The impersonation of legitimate service providers, such as delivery companies and emails being sent to victims, falsely pretending to be government institutions, were some examples of impersonation scams in the last few years. Through advertising custom built fraudulent apps and offering phishing templates, criminals have also reached a level in which they are openly marketing their scams online in exchange for money.15

Fortunately, there are signs and ways to identify recent social fraud in order for anti-financial crime (AFC) professionals to remain constantly aware, as well as mitigate and report when necessary. For instance, an unusually large cash withdrawal or wire transfer activity that are not consistent with the customer’s expected activity can raise some concerns. In the example of romance scams, victims commonly attempt to wire funds to an individual, often situated in a different jurisdiction, and after being instructed by the suspect to do so. This nature of activity becomes further concerning when the victim claims the purpose of the wire or cash withdrawal is financial support to their “significant other,” especially when no familial relationship can be established between the victim and the perpetrator. Impersonation scams and identity fraud can also be identified and triggered as a result of a deviation in the victim’s expected level of activity. For example, there may be a sudden and unusual increase in a victim’s purchases of gift cards, cash withdrawals or wire activity for the stated purpose of cryptocurrency investments or business opportunities. If questioned, the victim often states they were persuaded to invest in a particular business opportunity or a cryptocurrency that yields high returns. In these instances, the perpetrator is likely impersonating a legitimate organisation or has committed identity theft to appear genuine to the victim.

Fraud and Money Laundering

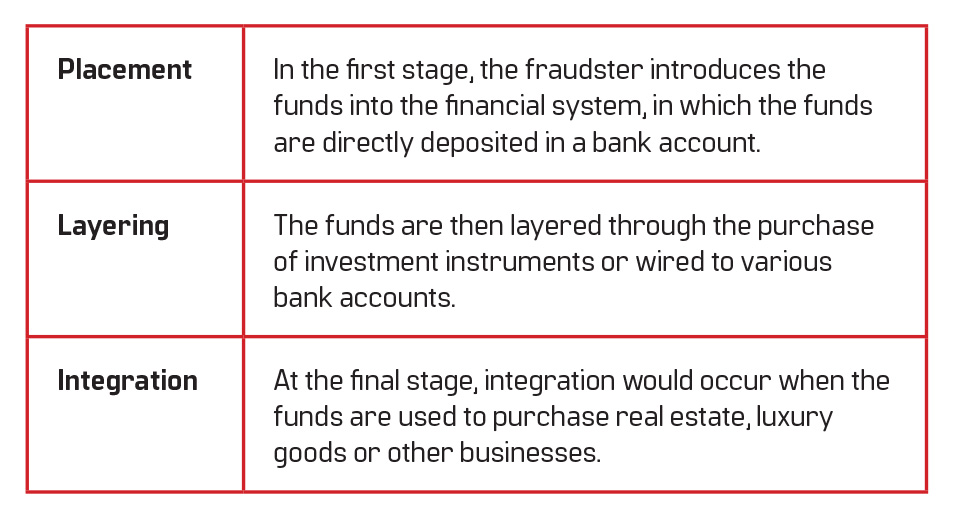

Money laundering becomes necessary for the fraudsters following their illegal financial gain. To make use of their money, the fraudster’s goal is now to disguise the origin of their funds.16 Relying on money laundering to legitimise ill-gotten funds extends to other forms of crime such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, embezzlement, organised crime, bribery and illegal arms sales often seek to launder their dirty funds as well. To successfully enjoy their illegitimate funds, fraudsters would typically have to follow through with all the three stages of money laundering: placement, layering and integration.17

Fraud and Money Laundering Legal Remedies

In the event of falling victim to fraud, it is advised to contact the local police authority where the financial crime took place. If the fraudster is known and can be traced, and if there is enough evidence presented to the police following the investigation, charges can be laid against the fraudster. To compensate for the damages suffered, the victims can also press civil charges. The banks in each particular jurisdiction are now required to implement and continue improving their AML regime. With the help of innovative tools and techniques established in each bank’s money laundering department, the detection and reporting of fraud have also aided law enforcement (LE) in tracing the guilty parties and holding them accountable for their illegal practices.

Further Protection

Further protection can be sought and obtained by way of insurance. An emerging type of insurance for businesses, in response to cybersecurity and online data breaches for sensitive personal information, is cyber insurance. It helps protect organisations from the repercussions of cyberattacks and data security breaches, avoid business disruption and possibly recover the financial cost of the hack.18 In addition, financial institutions (FIs) are adopting artificial intelligence and robotics to monitor, detect, and report fraudulent transactions accordingly.

In 2019, banks in the UK agreed to follow a new code of practice named the contingent reimbursement model. This was put in place to provide victims with fair opportunities to possibly obtain a refund in case of losing their funds to fraud.19

Conclusion

Although the motivation and opportunities have more or less remained the same, fraud has managed to continue to exist, adapt and even post a larger risk than ever before. As is evident throughout history, fraud was always presenting itself in various forms and has been a constant threat to individuals and businesses alike. As technology continued to develop, so did the fraudsters by adopting innovative tactics and techniques to carry out their illegitimate practices.

The way forward in money laundering largely depends on each FI’s strategy to combat financial crime in its various forms. Continued close cooperation with LE and the disclosure of suspicious transactions is required. Investing in training and developing skilled professionals to report suspicious activity and transactions in each jurisdiction’s financial regulatory authority is also crucial for remaining one step ahead in terms of innovation by investing in the latest technology for monitoring, detecting and reporting purposes. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether it will ever be possible to eradicate fraud with the advancement of technology.

Murad Zada, compliance analyst, Tether, murad.zada@tether.to

- George Kamel, “9 common types of fraud. In: Ramsey Solutions,” Ramsey, 19 January 2022 https://www.ramseysolutions.com/insurance/types-of-fraud

- “The psychology of Fraudsters,” Spam Laws, https://www.spamlaws.com/psy-frauds.html

- “Fraud Crime: Costs, Perpetrators, and Victims,” OVC Archive, https://www.ncjrs.gov/ovc_archives/reports/fraud/psvf/chap1.htm

- Andrei Tapalaga, “The Scammer Who Sold the Eiffel Tower Twice,” Medium, 1 January 2021, https://historyofyesterday.com/the-scammer-who-sold-the-eiffel-tower-twice-8db6a1e6f059

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jeff Maysh, “The Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower. Twice.” Smithsonian Magazine, 9 March 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/man-who-sold-eiffel-tower-twice-180958370/

- Jack Duval, “The “Rumanian Box” Fraud as Wall Street Metaphor,” Bantam, 5 June 2018, https://www.bant.am/blog/the-rumanian-box-fraud-as-wall-street-metaphor

- David Gaudio, “Top Digital Banking & Fraud Prevention Trends for 2021,” OneSpan, 18 January 2021, https://www.onespan.com/blog/top-digital-banking-fraud-prevention-trends-for-2021

- Ibid.

- “Romance scams,” FBI, https://www.fbi.gov/scams-and-safety/common-scams-and-crimes/romance-scams

- Ibid.

- “Criminals exploit the COVID-19 pandemic with the rise in scams targeting victims online,” UK Finance, https://www.ukfinance.org.uk/press/press-releases/criminals-exploit-covid-19-pandemic-rise-scams-targeting-victims-online

- Ibid.

- “What is Money Laundering?” Financial Action Task Force, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/faq/moneylaundering/

- Ibid.

- Danny Palmer, “What is cyber insurance? Everything you need to know about what it covers and how it works,” ZDNet, 5 March 2021, https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-cyber-insurance-everything-you-need-to-know-about-what-it-covers-and-how-it-works/

- Miles Brignall, “Victims of fraud: how to get your money back from your bank,” The Guardian, 2 October 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/money/2021/oct/02/victims-fraud-how-to-get-your-money-back-bank

Relevant information is given.