Inclusion is a popular topic. The West has recently aimed at placing all members of society on an equal footing: minority groups, the elderly, the disabled, women, men and others. Inclusion is a movement steered at giving all human beings the same opportunities and removing―as far as possible―any discrimination or barrier to fulfillment.1

It would have been inconceivable not to integrate finance into this concept of inclusion. The goal of financial inclusion is to make finance accessible to as many people as possible.

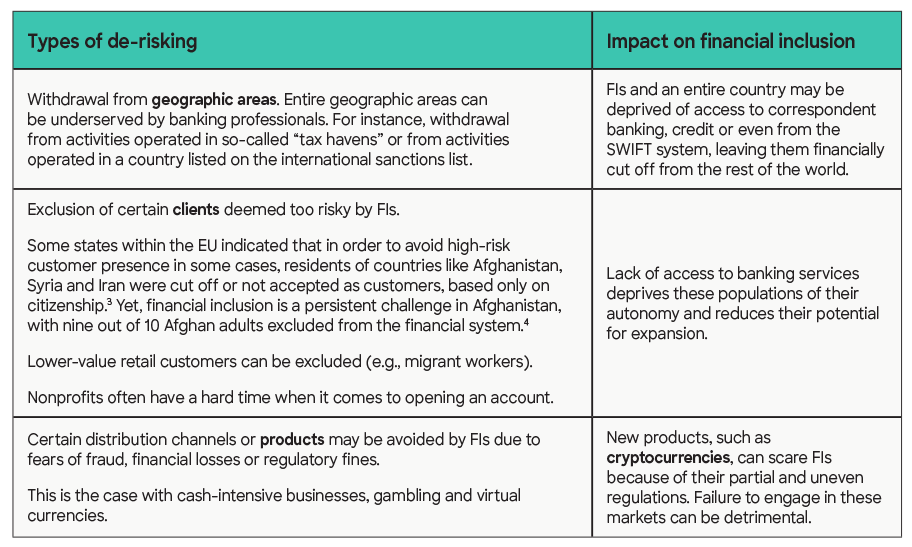

Conversely, de-risking is a form of exclusion. For professionals subject to the fight against financial crime―whether financial institutions (FIs) or other operators―it involves withdrawing from certain activities or territories, or even refusing to serve certain clients deemed too risky.2 The risk of financial or reputational loss can indeed be too great in some cases compared to the profit a product can generate. To be viable, a company thinks primarily in terms of profit. De-risking avoids costly preventive measures for the company and for a company de-risking is often seen as business-friendly.

Where inclusion leads to a unifying effect, de-risking produces an opposite result; for this reason, we can assert that de-risking is a threat to financial inclusion.

This is but theoretical. What is it like in the EU? What does real life teach us?

From a real-life point of view, de-risking threatens financial inclusion

Table 1: Types of de-risking and their impact on financial inclusion

Companies want to maximize profits and tend to opt for de-risking; however, they must take international regulations into account. International legal instruments force them to withdraw from certain sectors, while other instruments tend to encourage them to promote financial inclusion.

Sometimes corporations cannot help

but de-risk

International sanction regimes directly lead to the disengagement of companies and promote financial exclusion. Countries in general, and particularly member countries of the EU, must comply with international sanctions. These sanctions oblige them to restrict or even prohibit activities in certain countries or with certain clients/companies. Iran is a blatant example of this financial exclusion.5 Member states of the EU must comply with the international sanctions of the EU and often with those of the U.S. or other countries, such as a list of products prohibited from import and export (including certain financial products) or list of persons whose financial assets must be seized.

Complying with financial inclusion legislation

Legislation promoting financial inclusion also exists and leaves no choice to businesses. Thus, in the EU, the directive on payment accounts gives people the right to a basic payment account regardless of a person’s place of residence or financial situation.6 It is a legal mechanism that guarantees everyone the right to benefit from a bank account with basic services, even if a bank refuses to open an account. This mechanism aims to ensure financial and social inclusion by allowing everyone to have access to essential banking services. In France, this request for access to the account is made to the Banque de France, which is required to indicate an FI that is able to respond favorably to the request. This mechanism does not exist everywhere in the world. But almost all countries reviewed by MONEYVAL indicated they have policies and programs in place to ensure that socially disadvantaged persons (i.e., migrant workers, persons with low incomes, etc.) are able to obtain basic access to the financial system.7 These basic services include payment accounts through which consumers are able to carry out the following transactions: place funds, withdraw cash and execute and receive payment transactions to and from third parties, including the execution of credit transfer.

But even though the right to a basic account is legally enshrined within the EU, experience and research have begun to raise awareness that households living in poverty need access to a comprehensive range of financial services.8

For its part, it seems that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has taken the measure of the problem. FATF is at the top of the decision-making pyramid in the fight against money laundering and counter-terrorist financing and FATF recommendations end up in the legislations of most countries around the world. FATF is considering modifying somewhat its recommendations in order to reduce de-risking.9 De-risking, carried out too often, leads to many problems (if customers or certain products/geographic areas are left with no banking services, alternative solutions will be used, such as informal finance).

According to a FATF report, “In February 2021, the FATF Plenary agreed to establish a project team to analyze and understand better the unintended consequences resulting from the FATF Standards and their implementation. This project examines the unintended consequences related to four broad themes,” among which were (1) de-risking and (2) financial exclusion.10

In 2023, FATF amended its Recommendation 8, concerning nonprofit organizations; those subject to anti-money laundering (AML) regulations tend to reduce their activities with these organizations in order to exclude any risk of involvement in corruption or terrorist financing. The amended Recommendation 8 advocates for promoting the financial inclusion of nonprofit organizations.

In February 2025, FATF Recommendation 1 was amended. This recommendation is essential and concerns the obligation to implement a risk assessment using the risk-based approach methodology. The amendment reviewed the FATF standards and guidance on financial inclusion to allow for simplified due diligence measures in low-risk situations. The objective here is likely to reduce the burden of compliance controls and promote financial inclusion.

This is a good reason to take the time to prepare for ACAMS’ free social certificate on financial inclusion, which covers financial inclusion and risk assessment.11

A growing number of viable solutions fostering financial inclusion

Recently, new technologies have also made it possible to provide solutions to promote financial inclusion for populations lacking access to banking services

Hawala, an alternative money transfer system, has been around for a long time, offering solutions to underbanked populations and partially compensates for the shortage of traditional banking services. (“Hawaladars,” or informal money changers/brokers/agents, offer numerous services, including credit services.)12 This alternative system talks loudly in many parts of the world; in principle, all underbanked regions use hawala.

Recently, new technologies have also made it possible to provide solutions to promote financial inclusion for populations lacking access to banking services.

Fintech companies can be an option, providing a solution for people without access to the traditional banking system and payment methods that require opening a bank account. Prepaid cards, for example, do not require you to open a bank account.

This is also the case for money services companies, such as money transfer companies (Western Union or MoneyGram), which provide cash access in the most remote corners of the planet. These money transfer companies are nothing more than formal companies using the same principles as hawala. People who receive a transfer from a money transfer company can withdraw cash even without having a bank account, and this cash can be withdrawn in shops or any other location approved by the money transfer company. This is how a resident of a remote African village with no nearby banking institution and no bank account can receive funds sent to them by a family member working in Europe.

Conclusion

De-risking is a threat to financial inclusion. Financial inclusion and profits are often not compatible―and a company’s primary objective is to make a profit.

When given the choice, companies, after assessing their risks and determining their risk appetite, tend to prefer de-risking. The mere idea of having to implement numerous costly compliance solutions to reduce regulatory risks leads them to choose the most advantageous and least risky products, customers and geographic areas. In other words, they opt for products that generate the most revenue and carry the least risk of loss.

However, the leeway given to companies tends to be limited. They find themselves squeezed between opposing legal obligations: international sanctions that encourage financial exclusion and AML/counter-terrorist financing (CTF) obligations that seem to pull in the opposite direction. The fight against money laundering and terrorist financing tends to promote financial inclusion in order to maintain control over activities. For AML/CTF, the bigger the battlefield, the better, so financial inclusion is a must, whereas international sanctions tend to provoke financial exclusion in order to weaken countries and populations without resorting to war (and financial exclusion is a must)―two different objectives. It is up to the company to navigate.

Nathalie Bosse, CAMS, CGSS, T&C director, nathalie.bosse@mailo.com, ![]()

- “Glossary: social inclusion and equity,” Unesco World Heritage Convention, https://whc.unesco.org/en/glossary/365/

- “High-Level Synopsis of the Stocktake of the Unintended Consequences of the FATF Standards,” Financial Action Task Force, October 27, 2021, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/reports/Unintended-Consequences.pdf

- “Report: ‘De-risking’ within MONEYVAL states and territories,” Council of Europe, April 2015, https://rm.coe.int/report-de-risking-within-moneyval-states-and-territories/168071510a

- “Afghanistan: World Bank, ARTF Support Access to Finance for Small Businesses, Women’s Economic Inclusion with $16M Grant,” World Bank Group, April 3, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/04/03/afghanistan-world-bank-artf-support-access-to-finance-for-small-businesses-women-s-economic-inclusion-with-16m-grant

- “EU sanctions against Iran,” European Council, July 15, 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/fr/policies/sanctions-against-iran/

- “Directive 2014/92/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on the comparability of fees related to payment accounts, payment account switching and access to payment accounts with basic features,” European Union, July 23, 2014, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0092

- “Report: ‘De-risking’ within MONEYVAL states and territories,” Council of Europe, April 2015, https://rm.coe.int/report-de-risking-within-moneyval-states-and-territories/168071510a

- “Financial inclusion,” FinDev Gateway, https://www.findevgateway.org/fr/inclusion-financiere

- “High-Level Synopsis of the Stocktake of the Unintended Consequences of the FATF Standards,” Financial Action Task Force, October 27, 2021, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/reports/Unintended-Consequences.pdf

- Ibid.

- “Enhancing Financial Inclusion With a Risk-Based Approach’,” ACAMS, https://www.acams.org/en/training/certificates/enhancing-financial-inclusion#faqs-739af089

- “The Hawala System: Its operations and misuse,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2023, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/AOTP/Hawala_Digital.pdf