Good afternoon Chairman Sasse, Ranking Member Donnelly and distinguished members of the subcommittee. My name is Dennis M. Lormel. I have been engaged in the fight against money laundering and illicit finance for 45 years. Between my law enforcement experience and my private sector consulting experience, as a subject matter expert, I have developed a unique perspective regarding the benefits and burdens of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). Having served for 31 years in the government, 28 years as a special agent in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), I was the direct beneficiary of BSA reporting. Now, having been in the private sector working as a consultant and subject-matter expert, primarily with the financial services industry, I have become sensitive to the burdens and challenges of BSA reporting encountered by financial institutions. Those burdens and challenges are driven in part by regulatory requirements and expectations, as well as by the lack of consistent feedback mechanisms from law enforcement regarding the value of BSA reporting. Make no mistake, BSA reporting is essential to law enforcement’s ability to defend our national security and the economy from the threats posed by terrorism, counterintelligence and criminal adversaries. Therefore, having a thoughtful discussion about how to meaningfully enhance and not diminish the effectiveness and efficiency of BSA reporting is critically important to all stakeholders.

Money laundering and other forms of illicit finance are an extremely important topic, especially when placed in context with BSA reporting requirements and expectations. I had the privilege of testifying before the Senate Banking Committee on January 9, 2018. As subcommittee members may recall, that hearing addressed “Combating Money Laundering and Other Illicit Finance: Opportunities to Reform and Strengthen BSA Enforcement.” I applaud the subcommittee for holding this hearing to delve deeper into this important topic. The reality is that terrorists, terrorist organizations, spies, criminals and criminal organizations invariably rely on the financial system to move and access funding. The one commonality that terrorists, spies and criminals share is the need for funding. Without adequate funding, bad actors are much less likely to succeed with their nefarious activities. Therefore, the more effective and efficient we can make BSA reporting, the more challenging and disruptive it will be for bad actors to move and access needed funding.

I would like to refer to my written statement from the January 9, 2018 hearing as a framework to build on with my testimony today. As I stated in that session: “In using the financial system, criminals and terrorists are confronted with distinct contrasts. On one hand, the financial system serves as a facilitation tool enabling bad actors to have continuous access to funding. On the other hand, the financial system serves as a detection mechanism. Illicit funds can be identified and interdicted through monitoring and investigation. Financing is the lifeblood of criminal and terrorist organizations. At the same time, financing is one of their major vulnerabilities.”1

By understanding how criminals and terrorists launder money and avoid detection; how financial institutions succeed in targeting them; how law enforcement can leverage financial intelligence derived from financial institution; and how the funding flows involving various criminal activities can differ or be similar; financial institutions position themselves to better detect and not facilitate money laundering. Once suspicious activity has been identified and reported, law enforcement is better positioned to interdict and disrupt said criminal activity. The more productively financial institutions and law enforcement can collaborate with each other and share information, the more effective and efficient BSA reporting will be.

You asked me to provide my perspective today on how criminal organizations launder money and avoid detection by financial institutions and to include the following topics:

- Money laundering issues relating to narcotics trafficking, trade-based money laundering, human trafficking and real estate money laundering;

- The development and implementation of money laundering typologies to fight crimes such as, but not limited to, human trafficking;

- Effective means of cooperation and coordination with law enforcement officials;

- How to improve information sharing between individual financial institutions and with law enforcement.

Background

Before addressing the four bullet points above, it is important to establish who we are dealing with; in what context we are dealing with them; discuss the nexus between money laundering and fraud, and how that relates to predicate offenses or specified unlawful activities; and visualize the flow of funds as to how bad actors use the financial system.

Who are we dealing with regarding the myriad of criminal offenses? We are dealing with individuals, groups of individuals, domestic criminal organizations, transnational criminal organizations, homegrown violent extremists and terrorist operatives, and terrorist organizations. Bad actors usually have the advantage of being more proactive. BSA reporting is inherently reactive. This gives the bad actors an advantage, which is a challenge for financial institutions and law enforcement. Another challenge is that the different categories of bad actors set forth above will interact with each other if it is in their mutual best interest. This is particularly true with transnational criminal organizations and terrorist organizations. This is referred to as the convergence between criminals and terrorists.

There is a nexus between fraud and money laundering. Fraud and money laundering are interconnected. The proceeds of fraud and other predicate offenses or specified unlawful activities need to be laundered. Taking this a step further, if you list most predicate offenses, which would include drug trafficking, trade-based money laundering, human trafficking and real estate fraud, they will most likely contain elements of fraud and require money laundering. If you list predicate offenses and placed fraud on the top of the list and money laundering at the bottom of the list and envision the list to be a sandwich, the predicate offenses would represent the meat. Fraud and money laundering would be the gourmet bread. A great sandwich requires great bread. Successful criminal activity requires fraud and money laundering.

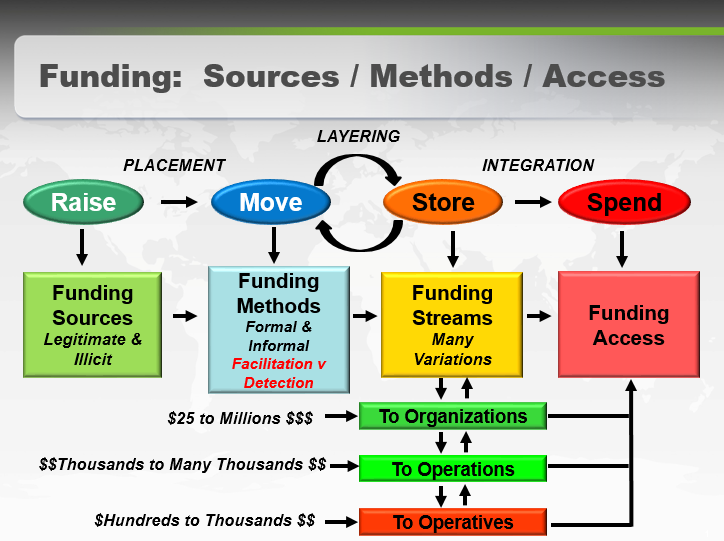

It is important to visualize the flow of funds. Regardless of the nature of the predicate offense, and how similar or different they are, and how similarly or differently they flow through the financial system, the process is the same. Criminals and terrorists raise, move, store and spend funds. This is the basic funding flow. When criminals raise money the source of funds will be illicit. When terrorists raise money the source of funds will be legitimate or illegitimate. Funds are then moved either through the formal or informal financial systems. Funding will be stored and will either continue to be stored or continue to be moved and stored and then spent. This is where funding flows for different criminal activity may differ more significantly. Following the moving and storage flow, the funds are spent. Money laundering is a three-step process: placement, layering and integration. When money is raised and moved, this is the placement stage of money laundering. When money is moved and stored, it is the layering stage of money laundering. The more the money is moved and stored, the more seemingly legitimized the funds become. When the money flows from being stored to spent, it represents the integration stage of money laundering. This is where funding is accessed as being seemingly legitimate in furtherance of nefarious purposes. As funds flow through the moving and storing phases, this is where financial institutions are facilitation tools or detection mechanisms. Below is a flow chart visualizing the funding flow described above. The funding flow below the funding streams box relate more directly to terrorist financing, although it could relate to transnational criminal organizations as well. The rest of the funding flow is consistent for criminals and terrorists alike.

The main distinction between terrorist financing and criminal money laundering is that terrorist financing tends to be linear and criminal money laundering tends to be circular. In that regard, in terrorism, the spend or funding access flows linearly to support a terrorist activity. In criminal money laundering, the spend or funding access flows back to the criminal or criminal enterprise in a circular manner.

Money Laundering Issues Relating to Narcotics Trafficking, Trade-Based Money Laundering, Human Trafficking and Real Estate Money Laundering

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an international governmental body that serves as the standard bearer for combating money laundering. The FATF 40 Recommendations set out a comprehensive and consistent framework of measures which countries should implement in order to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. Recommendation 3, of the FATF 40 Recommendations, states that “Countries should apply the crime of money laundering to all serious offenses with a view to include the widest range of predicate offenses.”2 Regardless of differences in the myriad of predicate offenses, law enforcement should include charges of money laundering when pursuing criminal prosecution in activities to include narcotics trafficking, trade-based money laundering, human trafficking and real estate money laundering. This reinforces why BSA reporting is so important.

When assessing money laundering issues regarding narcotics trafficking, trade-based money laundering, human trafficking and real estate money laundering, the starting point is the scope of the crime problem. Drug trafficking has long been and continues to be the most prolific global crime problem. Human trafficking has evolved to become the second most significant global crime problem. It is difficult to quantify trade-based money laundering. However, trade-based money laundering is, in a sense, a growth industry. Trade-based money laundering is a global problem but centered more regionally, where there are free trade zones. There are many real-estate-related frauds. For purposes of this discussion, much attention has been placed on the purchase of highly expensive real estate in select geographic regions around the world. Much of this real estate is purchased through shell companies or nominees and is paid for in cash.

The next consideration to assess is who we are dealing with, how are they likely to touch the financial system and where are the touch points geographically. Drug trafficking is more inclined to include domestic and transnational criminal organizations. Terrorist organizations will also engage in the sale of narcotics as a source of income. Human trafficking will more likely involve groups of individuals and both domestic and transnational criminal organizations. Trade-based money laundering will more likely involve individuals, groups of individuals and transnational criminal organizations. For the most part, real estate money laundering involves individuals or groups of individuals. The key from an anti-money laundering (AML) perspective is to understand and identify the touch points individual criminals and groups have with financial institutions.

Narcotics trafficking and human trafficking groups can overlap by using the same supply chain or channels and involve the same groups. To the extent narcotics and human trafficking operations overlap, they will more likely have similar distribution flows. In any event, narcotics trafficking and human trafficking are more likely to have greater similarities. Trade-based money laundering is unique to other criminal activity in that it relies more on false invoicing and a wider variety of commodities. Real estate money laundering is unique to itself because it relies more on individuals and not organizations and involves cash to purchase expensive fixed real estate. Thus, there is no supply chain or channel in these real estate money laundering schemes. It should be noted that there could be exceptions to these norms.

When you understand the crime problems in terms of scope and geography, and in combination with who you are dealing with, you can begin to visualize the funding flow in terms of how the bad actors raise, move, store and spend their ill-gotten gains. An important key is to simplify the funding flow as much as possible. From an AML perspective, drug trafficking is not only the most prolific crime problem, it also represents the broadest exposure to financial institutions ranging from smurfs or mules structuring transactions under the $10,000 currency transaction report (CTR) threshold to the multi-million dollar movement of drug funds. To further complicate this challenge, drug traffickers exploit a variety of facilitation tools, such as shell companies, to avoid AML detection. Transnational drug trafficking organizations frequently engage in trade-based money laundering to move and convert large sums of money, across the border between countries, from one currency to another. One such common scheme is referred to as the Black Market Peso Exchange (BPME). This is where money brokers are used by drug traffickers to convert U.S. dollars or euros to pesos through the sale of commodities, such as clothing or electronic equipment. As will be discussed later, patterns of funding activity or typologies involving human trafficking have been more predictable for financial institutions and law enforcement. Trade-based money laundering presents a significant AML challenge for financial institutions to identify. Under- and over-invoicing is extremely difficult for financial institutions to identify. Trade and shipping documents tend to be less automated and more paper-centric, making analysis more difficult. As mentioned above, drug trafficking organizations rely on BPME, a form of trade-based money laundering, to convert the proceeds of drugs sold in the U.S. or Europe from dollars and euros into pesos in Mexico and Colombia through the trade of commodities by money brokers. By their nature, BPME schemes are difficult for financial institutions to identify through traditional AML monitoring.

An example of a significant BPME case was Operation Fashion Police. In a major takedown in Los Angeles on September 10, 2014, nearly 1,000 federal, state and local law enforcement officers seized approximately $100 million in cash, arrested nine subjects and searched dozens of businesses in the city’s downtown fashion district alleged to have laundered money for Mexican drug cartels. Three fashion businesses were indicted. One was indicted for accepting bulk cash and funneling money through 17 businesses. The other two companies were indicted for structuring deposits of bulk cash to avoid reporting requirements. From reviewing the statements of facts in federal charging documents, it appears that considerable evidence was developed from CTRs and suspicious activity reports (SARs). As a result of this case, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued a Geographic Targeting Order (GTO) covering the Los Angeles fashion district.

With respect to real estate money laundering, FinCEN issued and subsequently renewed GTOs in six major metropolitan areas in the U.S. regarding the all-cash purchase of luxury real estate. The GTOs required U.S. title insurance companies to identify natural persons behind shell companies used to make the all-cash purchases. This crime problem demonstrates the significance of the money laundering risk presented by the issue of beneficial ownership.

The Development and Implementation of Money Laundering Typologies to Fight Crimes Such As, But Not Limited To, Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a heinous crime problem. I believe that AML professionals are dedicated and motivated to protect their financial institutions from the threat of money laundering and the risks associated with being exploited as a facilitation tool by bad actors. Two areas where this is particularly true are human trafficking and terrorist financing. As mentioned above, patterns of activity or typologies involving human trafficking have been more predictable for financial institutions and law enforcement.

Before focusing more specifically on human trafficking, we should look more broadly at developing typologies to identify suspicious activity for criminal offenses. The BSA requires financial institutions to establish AML programs reasonably designed to identify and report suspicious activity. This starts with identifying red flags associated with each criminal activity. Red flags are generic warning signs. They are indicators that there might be suspicious activity. There are many lists of red flags regarding criminal activities available to financial institutions. From the list of generic red flags, I encourage financial institutions I work with to take generic red flags more specific to their institutional risk and to customize them to their institutional risk environment.

One mechanism to develop money laundering typologies is to review federal court charging documents such as an indictment, plea agreement, criminal information and search warrant. In the affidavit supporting the charging document there will be a statement of facts. The statement of facts frequently sets forth the alleged typology used to commit the criminal offense. This is one mechanism where financial institutions can enhance the scenarios they use for transaction monitoring.

With respect to human trafficking, there are multiple sources of red flags available to financial institutions. Other red flag guidance is available from FATF, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), the FBI and other viable sources. It should be noted that the Polaris Project has written a great reference guide about human slavery (trafficking), entitled “The Typology of Modern Slavery.3 In addition, human trafficking is widely discussed at industry AML training conferences. Training is one of the core pillars of an AML program. Human smuggling typologies and warning signs are frequent topics.

The Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) has made human smuggling a long time priority. They started a working group in 2010 with a group of major banks and HSI. Bank analysts and HSI analysts developed patterns of activity or typologies consistent with human smuggling. JPMorgan Chase had a team of special investigators who conducted targeted transaction monitoring and identified potential suspicious activity. ACAMS gave JPMorgan Chase and HSI a special award in recognition of their outstanding collaboration. Another outstanding example of public and private sector partnerships occurred in January 2018, in the run-up to the Super Bowl. The ACAMS Minneapolis Chapter held a half-day learning event focused entirely on human slavery/trafficking. I was proud to be the first speaker. U.S. Bank, HSI and the U.S. attorney’s office in Minneapolis collaborated to develop typologies to identify human sex trafficking specifically related to travel for the Super Bowl. These types of initiatives have a great impact on crime problems like human trafficking. I must give a cautionary comment that this type of initiative is not as easy as it sounds. It can be costly. There are regulatory concerns and other impediments that must be overcome. The March-May 2018 issue of ACAMS Today magazine had a detailed article about the Minneapolis learning event.4

Effective Means of Cooperation and Coordination with Law Enforcement Officials

The most effective means of cooperation and coordination between financial institutions and law enforcement is through sustainable public and private partnerships. In addition to cooperation and coordination, these partnerships must include communication. Establishing viable partnerships begins with perspective. You must understand the perspective of your partner and overcome any impediments caused by differences in perspective. For example, the primary perspective of financial institutions is to protect the integrity of the institution, whereas the primary perspective of law enforcement is to develop evidence to obtain criminal prosecutions and to disrupt terrorist activity. At times, these perspectives can clash. In understanding perspectives and working through potential impediments, you must develop win-win situations for each partner. It is important to understand that a win-win situation may not be a best-case scenario but rather a good-case scenario. Once that has been established you can leverage the capabilities and capacity of partners to attain that good-case scenario in order to establish the win-win situation. When that foundation is established, partners can develop sustainable, innovative and impactful proactive measures to support law enforcement investigative initiatives.

The targeted monitoring projects described above involving JPMorgan Chase, and subsequently U.S. Bank with HSI, are outstanding examples of public and private sector partnerships. Financial institutions conduct baseline transaction monitoring, which is inherently reactive. The rate of SARs used to predicate or enhance law enforcement investigations from baseline transaction monitoring is low. This is where we must improve the effectiveness and efficiency of SAR reporting. Targeted monitoring projects result in a more proactive approach and a higher SAR utilization rate. Other outstanding examples of meaningful public and private sector partnerships is where both the FBI’s Financial Crimes Section and Terrorist Financing Operations Section (TFOS) have ongoing national bank working groups in which they provide targeted information and feedback to participating financial institutions. The information sharing and feedback result in better quality BSA reporting.

As I stated in the January 9, 2018 hearing: “One of the most productive examples of public and private sector partnership, and information sharing, is the Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Task Force (JMLIT) in the U.K. JMLIT was formed by the government National Crimes Agency (NCA) in partnership with the financial sector to combat high end money laundering. JMLIT was established as a business-as-usual function in May 2016. It has been developed with partners in government, the British Bankers Association, law enforcement and more than 40 major U.K. and international banks. I am hopeful that the U.S. can assess and work through information sharing and privacy concerns in order to replicate the U.K. JMLIT model.”5

How to Improve Information Sharing Between Individual Financial Institutions and with Law Enforcement

As I stated in the January 9, 2018 hearing: “As an extension of public and private partnerships, we should consider how to improve information sharing. The PATRIOT Act provided us with information sharing vehicles such as Section 314(a) where financial institutions can share financial information with law enforcement and Section 314(b) where financial institutions can share information with each other. Efforts should be made to enhance Section 314 information sharing in the current environment. In addition, any proposed enhancements to the BSA should consider additional information sharing mechanisms. The more we can do to enhance information sharing, the more meaningful information will be for law enforcement and the more detrimental to criminals and terrorists. During their plenary session in June 2017, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) stressed the importance of information sharing to effectively address terrorist financing. I have always been a huge proponent of information sharing to the extent legally allowable.”6

Law enforcement outreach is extremely important. At the grassroots or jurisdiction and/or field office level, there are informal working groups. Each of the 94 U.S. attorney’s offices in the U.S. has law enforcement SAR review teams. An assistant U.S. attorney in each judicial district leads the SAR review team. SAR review teams involve personnel from federal law enforcement. In most SAR review team locations, Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Criminal Investigations plays a lead role. Depending on the jurisdiction, SAR review teams will also include state and local law enforcement agencies. Financial institutions, at the grassroots level, should participate with law enforcement at the jurisdiction level. Federal law enforcement agencies also have outreach programs at the national level and/or initiative-specific level. This is exemplified by the working groups the FBI Financial Crimes Section and TFOS host at the FBI headquarters.

Feedback to financial institutions from law enforcement regarding the value of BSA reporting, particularly the value of SARs, is inconsistent. There are a number of inherent impediments to establishing a feedback mechanism. Such include the nature of criminal investigations. From the point a SAR is filed to the point a case is concluded, it could be a period of one or more years. If a case is a grand jury investigation, information cannot be disclosed by law enforcement. In addition, law enforcement lacks the resources to consistently provide feedback. There are always new cases to move forward with and investigators do not have time to provide feedback. Impediments aside, there are no excuses for not providing feedback. As noted in discussing targeted monitoring initiatives, in those situations, consistent feedback from law enforcement is provided and the quality of financial institution BSA reporting is outstanding.

Countering the Threat by Enhancing BSA Reporting From a Law Enforcement Perspective

From my perspective, which includes my law enforcement experience and my private sector consulting experience, there are four issues that must be addressed in proposed legislation to improve or enhance BSA reporting effectiveness and efficiency. The first is less tangible or measurable and more challenging. The other three are more tangible. However, one of those three is less measurable. The first is regulatory requirements versus regulatory expectations. The other three, which are more tangible, are the CTR and SAR reporting thresholds, feedback mechanisms and beneficial ownership. I believe the reporting threshold and beneficial ownership are more measurable, whereas feedback mechanisms are not currently very measurable.

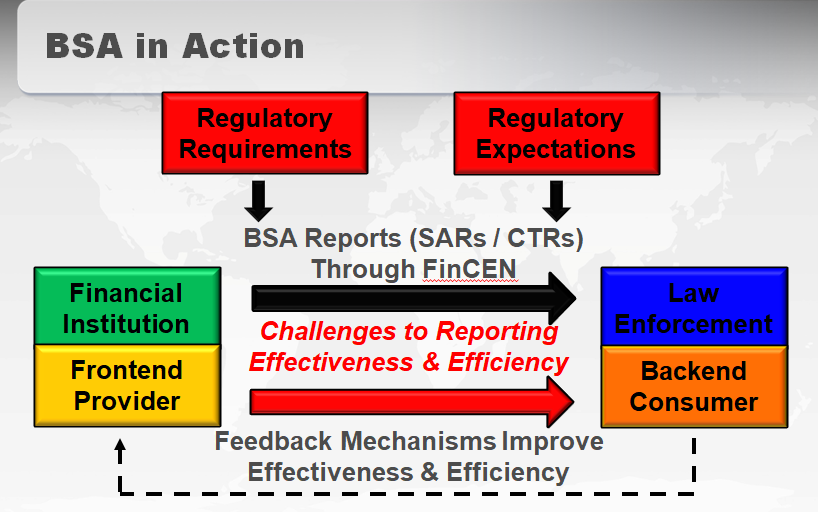

Basically, the flow of BSA reporting from financial institutions to law enforcement is extremely beneficial. However, when the filters of regulatory requirements and regulatory expectations are applied, especially the uncertainty of regulatory expectations, there is a drag or reduction in the flow and possibly the quality of BSA reporting. In keeping with the theme of the flow of information, we must consider the inconsistent feedback from law enforcement to financial institutions. Below is a flow chart that demonstrates the process of the dissemination of information.

If the space between the black and red arrows could be reduced, the real or perceived regulatory impediments would diminish and improve the flow of BSA reporting to law enforcement. An example of regulatory expectations is where financial institutions make a decision not to file a SAR. A frequent complaint I hear from AML compliance professionals is that they have to provide their regulators with more documentation for no-SAR decisions versus SAR filings. Consequently, financial institutions file SARs they otherwise would not, because of real or perceived regulatory expectations. These filings are not warranted. The time taken by financial institutions to document the no-SAR decision or to file SARs to merely satisfy regulators, coupled with the time required by law enforcement to review these SARs, is time wasted and is counterproductive.

If a consistent feedback mechanism could be developed from law enforcement and financial institutions, the broken line on the above flow chart would become more connected and would improve feedback and more importantly, improve the quality of BSA reporting. I believe a feedback mechanism should be developed and implemented through FinCEN, which is initiated by law enforcement. I further believe that SAR feedback would improve the quality of SAR submissions. I also believe that a SAR feedback mechanism would improve the morale of AML professionals who are involved in the SAR process. They would have a greater sense of accomplishment and satisfaction that their work contributes to law enforcement successes. Make no mistake; SARs play a significant role in law enforcement investigations. I believe that the FBI is assessing how to develop a more consistent SAR feedback mechanism.

My greatest concern about potential BSA enhancement legislation is any consideration to increase BSA CTR and SAR reporting thresholds. That would be devastating to law enforcement. With the current threat environment, especially with the terrorism threat of homegrown violent extremists, law enforcement needs as much financial intelligence as is legally available. Likewise, when you take into consideration the bandwidth of drug trafficking, the nuances of human trafficking and the challenge of trade-based money laundering, coupled with the variations of financial crimes, especially Ponzi schemes, raising BSA reporting thresholds will greatly diminish law enforcement’s capability to respond to these and other crime problems and to protect our national security and economy.

Financial intelligence, derived from financial institutions, enables law enforcement to better protect us. AML professionals have told me that increasing BSA reporting thresholds for CTRs and SARs would not likely save money and does not cause a burden. This is because financial institutions have automated systems set at the current thresholds. According to the FBI, and I have not been able to verify the statistics, if the CTR threshold is raised from the $10,000 threshold to $30,000, the FBI would lose 78 percent of financial intelligence derived from CTRs. In addition, the FBI advised that if the SAR threshold were raised to $50,000, they would anticipate an 80 percent loss in SAR filing intelligence. Finance is one of the biggest vulnerabilities of criminals and terrorists. The significant loss of any financial intelligence is a troubling detriment to law enforcement. The BSA is intended to support law enforcement, not to deter it.

I was advised by FBI executives that the FBI conducts data analysis of BSA filings, including CTRs and SARs, to enhance existing cases and to predicate new investigations. All FBI main subjects are searched against BSA data on a monthly basis. According to the FBI, they average hits on 4,000 BSA filings per month. The FBI also proactively uses data analysis to identify new cases. The FBI refers to this as targeted suspicious activity reports (TSARs). Searches are run using search terms for money laundering, terrorist financing, human trafficking, fraud, corruption, transnational organized crime and other schemes. I have also heard IRS case agents, while making case study presentations at recent conferences, discuss how they run similar BSA data checks to enhance their investigations. The loss of CTR and SAR reporting, especially above 50 percent, would be extremely detrimental to law enforcement investigations.

I have been advocating for beneficial ownership legislation since 2012. I have testified at hearings or briefed Congressional members and staff dating back to October 2001, about the vulnerabilities shell companies present to our financial system. This is especially true in dealing with the threat of terrorism, spies and criminals. As an example, Iran has been able to circumvent sanctions by using shell companies to provide them with access to the financial system. In one specific case, shell companies were used to allow the Alavi Foundation, Assa Corporation and the 650 Fifth Avenue Company (a partnership of Alavi and Assa) to hide the Iranian ownership of the 36-story building at 650 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to enact beneficial ownership legislation comes from the 2016 Mutual Evaluation of the U.S. conducted by FATF. FATF found that the U.S. has a well-developed AML regime. However, FATF noted that the system has serious gaps that impede timely access to beneficial ownership information.

Conclusion

Our threat environment is extremely concerning. Finance is one of the most important vulnerabilities to bad actors, and consequently, the threat environment. We must do whatever we can to exploit the vulnerability of bad actors and not allow them to succeed. When we consider enhancements to BSA reporting we must ensure we get it right. Those enhancements must be in the best interest of our country. That means ensuring law enforcement has the tools they need to protect national security and our economy.

Thank you for taking the time to hold this hearing and for affording me the opportunity to share my perspective on this important topic.

- Dennis M. Lormel, “Dennis M. Lormel’s Testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee’s Hearing,” ACAMS Today, January 9, 2018, https://www.acamstoday.org/dennis-lormel-testimony-senate-committees-hearing/

- “International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation: The FATF Recommendations,” Financial Action Task Force, February 2012, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF_Recommendations.pdf

- “The Typology of Modern Slavery,” Polaris, https://polarisproject.org/sites/default/files/Polaris-Typology-of-Modern-Slavery.pdf

- Sande Bayer and Shannon Bennett, “Providing a Greater Awareness of Human Trafficking Through Education in Minneapolis,” ACAMS Today, January 25, 2018, https://www.acamstoday.org/awareness-human-trafficking-through-education-minneapolis/

- Dennis M. Lormel, “Dennis M. Lormel’s Testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee’s Hearing,” ACAMS Today, January 9, 2018, https://www.acamstoday.org/dennis-lormel-testimony-senate-committees-hearing/

- Ibid.