How should financial institution compliance officers, analysts and investigators view the Islamic State? On one hand, as concerned citizens, they should view the Islamic State as the barbaric and thug-like terrorist organization they are. On the other hand, as compliance professionals, they should view the organization as a possible corporate customer and the organizational members as possible individual customers. The question then becomes: How do compliance professionals identify organizational and/or individual customers as being members or supporters of the Islamic State or other terrorist organizations?

One thing is certain about compliance professionals: they are dedicated and passionate about what they do. As they watch the atrocities caused by the Islamic State unfold, and as the danger to the U.S. and their Western allies becomes more pronounced, compliance professionals want to know what they can do to diminish the threat. The fact of the matter is there is a great deal they can do. After all, financial information is one of the major vulnerabilities for terrorists. The starting point for compliance professionals is knowing your customer and identifying risks associated with terrorist financing. In this instance, it is knowing more about the Islamic State and its members, as well as knowing more about like-minded terrorist groups and their members operating in Iraq, Syria and the surrounding region.

So, who are the Islamic State and like-minded groups that pose a threat to the West?

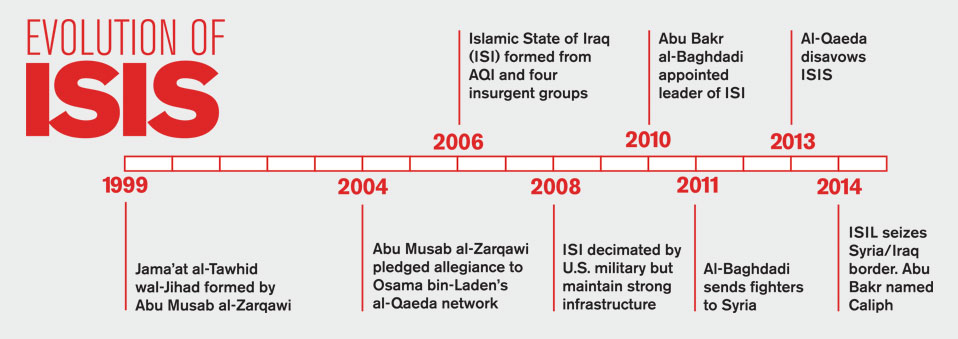

The Islamic State evolved from al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). The forerunner to AQI was a group called Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad. It was formed in 1999, by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The group moved to Iraq in 2003 to fight American forces, following the invasion of Iraq. In October 2004, al-Zarqawi officially pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda network. During that period, al-Zarqawi grew to become one of the most wanted terrorist in the world because of his brutal tactics. He was killed in an American airstrike on June 7, 2006. In October 2006, AQI merged with four other insurgent factions and changed their name to the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). By 2008, the ISI had been decimated by the U.S. military. Although seriously diminished, ISI maintained a strong infrastructure, to include a steady stream of financing. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was appointed the leader of ISI on May 16, 2010. Al-Baghdadi replenished the leadership and ranks of ISI by recruiting former Ba’athist military and intelligence officers who had served during the Saddam Hussein regime. These individuals were experienced Sunni fighters. Following the overthrow of Hussein, the U.S. disbanded the Iraqi military and then assisted the Iraqis in establishing a new military, which was predominantly Shiite. In the aftermath of the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq, in July 2012, al-Baghdadi announced that ISI was returning to their former strongholds in Iraq.

In August 2011, al-Baghdadi began sending experienced Syrian and Iraqi ISI fighters to Syria to establish a group there. Al-Baghdadi appointed a Syrian, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, to be in charge. He wanted the group to recruit fighters and establish cells throughout Syria. The group was named the al-Nusra Front and it grew rapidly. The instability and chaos in Syria and Iraq afforded ISI and the al-Nusra Front the opportunity to thrive and accumulate great wealth. In April 2013, al-Baghdadi announced that the al-Nusra Front had been established, financed and supported by ISI and that the two groups were merging under the name “Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham” (ISIS). The al-Nusra Front would not accept the merger and called on al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri to intercede. Al-Zawahiri ruled in favor of the al-Nusra Front and instructed ISIS to return to Iraq. ISIS refused and continued operating in Syria, as well as Iraq. Consequently, ISIS was disavowed by al-Qaeda in February 2014. ISIS is also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). ISIL is the acronym used by the U.S. government when discussing the group. The significance of the term “Levant” is that it covers Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Cyprus and part of southern Turkey. The U.S. understands that ISIL aspires to extend its presence and control beyond Syria and Iraq into each of these other territories.

While the al-Nusra Front has joined with other rebel groups in Syria and focused on fighting the Syrian government, ISIL was more focused on gaining control over as much territory as possible in Syria and Iraq. They took control of the Syrian and Iraqi border territory giving them greater flexibility to move their fighters between the two countries. On June 29, 2014, ISIL removed “Iraq and the Levant” from its name and it now refers to itself as the “Islamic State.” While announcing the name change to the Islamic State, the group advised they had established a caliphate in the vast territory it controls in Syria and Iraq. The Islamic State called for Muslims around the world to pledge allegiance to the caliph, Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi, ISIL’s leader. ISIL has been widely criticized by the Muslim community for their actions.

The Islamic State or ISIL has garnered daily media attention since June 2014, and is currently the most recognizable and visible terrorist group in the world. Its deep rooted sense of purpose and its politics, financial and military ability have transformed ISIL into a serious regional and global threat. It has amassed incredible wealth and has become the richest terrorist group in the world. The unlimited source of funds available to ISIL has enabled them to grow, gain power and military strength and enhance the level of threat they pose.

In mid-2014, intelligence sources estimated that ISIL had assets worth $2 billion

ISIL enjoys multiple funding streams. They have taken over oil wells in Syria and Iraq in territories they control. They also tax and extort funds from residents of territory they control, most notably in Mosul, Iraq. Other funding sources include payment of ransom from kidnapping, theft and sale of antiquities, looting and bank theft. To a much lesser degree, they derive funds from wealthy donors. They are self-sustaining and therefore not beholding to any benefactors. In mid-2014, intelligence sources estimated that ISIL had assets worth $2 billion.

ISIL is extremely sophisticated and has an effective command and control system. In addition to al-Baghdadi, ISIL has a defined leadership structure and sense of organization. They maintain committees overseeing finance, leadership, military matters, legal matters, foreign fighter assistance, security, intelligence and media. ISIL has ample equipment, much of which they gained in victories over the Iraqi and Syrian militaries. ISIL also has professional fighters, many of whom were formerly in the Iraqi military under Saddam Hussein, as noted earlier.

ISIL has between 20,000 and 30,000 fighters. Approximately 12,000 of these fighters are individuals from outside of Syria and Iraq. It is estimated that 2,000 foreign fighters come from Europe, while up to 200 come from the U.S. Many of the European and U.S. foreign fighters have been described as being misfits in their home countries and more fanatical than other fighters. It has been easy for foreign fighters to travel to Syria through Turkey, in particular, and other neighboring countries. Syria has become the pre-eminent location for al-Qaeda and ISIL to recruit, train and equip a growing number of extremists from foreign countries.

In addition to ISIL, the al-Nusra Front and other insurgent groups in Syria have also attracted many foreign fighters. Most foreign fighters are Sunni Muslims, who came to fight the Assad regime in Syria or the Shiite government in Iraq. Following the U.S. led airstrikes against terrorist targets in Syria on September 23, 2014, the U.S. government announced one of the bombing targets was an al-Qaeda group known as the Khorasan Group. This group is comprised of experienced al-Qaeda fighters from Pakistan and Afghanistan. They were sent to Syria to set up training camps. Because of the conflict in Syria, they were able to establish training facilities and operate freely. They are closely aligned with the al-Nusra Front. In announcing the bombing, the U.S. government stated that the Khorasan Group presented a more immediate threat to the U.S. than ISIL. The Khorasan Group has been working with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the al-Qaeda group located in Yemen, to make bombs that could get through airport security undetected. AQAP has al-Qaeda’s foremost bomb maker, Ibrahim al-Asiri, as a valued member. It is believed that the Khorasan Group was recruiting and training foreign fighters. The intent was that the foreign fighters would return to their countries and commit acts of terrorism. The combination of bomb making capability and foreign fighters returning home heightened the level of threat posed by the Khorasan Group. The bombings on September 23 seriously damaged the Khorasan Group’s training facilities and resulted in the death of their leader, Muhsin al-Fadhli.

Who are you dealing with at the group member level?

Individual members of these terrorist groups include leaders, facilitators, financiers, administrators and fighters. In terms of ISIL, members come primarily from Iraq and Syria. Other members are foreign fighters, mostly from countries in the region. Other foreign fighters come from Europe and the U.S. In terms of the al-Nusra Front, most fighters are from Syria, some from Iraq and others are foreign fighters, similar in composition to ISIL. The Khorasan Group is comprised of fighters from Pakistan and Afghanistan, who are in Syria to recruit and train foreign fighters. The alarming concern for Western countries is that foreign fighters traveling with European or American passports can travel freely throughout the West. If those fighters return to their home country or other Western countries, they pose a significant security threat. The fact that many of these individuals were misfits in their home countries and are extremely fanatical makes them a serious national security threat throughout Europe and the U.S.

To reiterate the question asked at the outset of this paper: How do compliance professionals identify organizational and/or individual customers as being members or supporters of the Islamic State or other terrorist organizations? With respect to the threat posed by ISIL, the al-Nusra Front, the Khorasan Group and other similar groups, compliance professionals must look at the terrorist financing threat on two levels: (1) the organizational level and (2), the individual operative level.

Organizational Operative Level

On the organizational level, compliance professionals must assess the flow of funds on three tracks. The first track is money that flows into the organization. In the case of ISIL, the group has spawned a for-profit business model based upon multiple funding sources as articulated earlier. The second track is money that flows from the organization to support organizational operations. Again, in the case of ISIL, money from the organization will flow through the finance committee with the approval of leadership. The money likely flows through facilitators and administrators to support operations, such as funding military activity or the cost of providing water, bread and electricity to inhabitants of territories ISIL controls. The third track is funding that probably flows from the financial committee through facilitators and administrators to fighters and other members of the organization. Once more, in the case of ISIL it could be money paid to fighters in the form of wages and other stipends or for other expenses incurred in support of executing their individual duties.

Identifying terrorist financing regarding ISIL or other terrorist groups at the organizational level is very challenging. The group will not be openly banking under the name ISIL or other names identifiable with the organization. They would most likely be reliant on front or shell companies and nominees to avoid detection. The chance that ISIL or ISIL fronts would have any direct banking relationships with Western banks would be extremely remote. Western banks could possibly have correspondent relationships with banks in the region that have some sort of banking relationship with ISIL. For example, ISIL is heavily engaged in the black market sale of oil in Turkey from oil wells it controls in Syria and Iraq. This is where Turkish banks could be susceptible of facilitating financial activity for ISIL. Banks throughout the region located in Jordan and Lebanon could also be used to facilitate banking activity for ISIL funding from oil and other funding sources. Venues such as Qatar, Kuwait and Dubai, which are cash friendly, could offer attractive and safe banking opportunities for ISIL as well. Much the same is likely true with select offshore banking locations. Due to the cash-based nature of the economies in Syria and Iraq, a considerable amount of financial activity will be carried out in cash transactions, which would be virtually impossible for Western banks to monitor or identify. Another variable is the prospect of using virtual currency to convert and move money.

Understanding the nature and complexity of the geographic risk in the region is essential for Western financial institutions

Understanding the nature and complexity of the geographic risk in the region is essential for Western financial institutions. In addition, understanding regional business risk is important. Are wire transfers being sent to and from the region, and do they comport to reasonable business activity? Because of the devastation to the infrastructure and the extreme number of refugees in Iraq and Syria, there is a tremendous need for humanitarian aid. Numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and charities are active throughout the region providing much needed humanitarian aid. Unfortunately, terrorist groups in the region syphon considerable funds from NGOs and charities to support their terrorist organizations. Charitable activity in the region, especially in Syria, should be considered a challenging and a sensitive red flag requiring enhanced due diligence (EDD).

Individual Operative Level

Identifying warning signs for funding individual members of ISIL and other terrorist groups in the region should be less challenging than identifying organizational warning signs. Nonetheless, identifying individual red flags is a challenge. Individual group members coming from Iraq, Syria and non-Western countries are much less likely to have a nexus to Western banks. Many will be unbanked. Unless receiving and spending funds from account holders in Western banks in the form of wire transfers or ATM activity, it is unlikely these individuals would be engaged with Western banks. Conversely, these individuals would be more inclined to be engaged in money services business (MSB) transactions and hawala activity.

Foreign fighters from Europe and the U.S. are more likely to be identifiable with Western banks and/or MSBs. In view of the serious threat these individuals pose, their identification by compliance professionals should be a critical priority. Individuals aspiring to be foreign fighters should be monitored for travel to Syria through Turkey and other points of entry to include Jordan, Lebanon and Israel. Compliance professionals should develop patterns of financial activity identifiable with travel regarding financial services their institution provides. Once these individuals arrive in Syria, other red flags, will become more prominent. Such red flags include:

- IP logins in areas of conflict such as near the Syrian border, to include Jordan and Lebanon, but particularly in Turkey

- Periods of transaction dormancy, which could be the result of terrorist training or engagement in combat

- ATM cash withdrawals in areas of conflict

- Wire transfers to areas of conflict

- Social media postings (many Western foreign fighters use social media)

Whether compliance professionals are looking at organizations or individuals, they should develop case typologies to enhance their detective capabilities. They should follow federal criminal and civil cases. In charging documents like informations, indictments and plea agreements, there will be a statement of facts setting forth the scenario or pattern of activity. Based on that scenario or pattern, case typologies can be developed. Other mechanisms that benefit the identification process include transaction monitoring, targeted transaction monitoring, negative media reports and law enforcement actions to include requests and legal process.

As noted at the outset, one thing is certain about compliance professionals: they are dedicated and passionate about what they do. Knowing they can make a tangible difference in identifying terrorist financing is something that will resonate and be a source of pride and meaningful accomplishment.