Myths continue to girdle virtual (crypto) currencies, including that they are anonymous and exclusively used by criminals to purchase items on the darknet or to launder money. Bitcoin is most commonly associated with these myths, despite the fact that it is not anonymous, but rather pseudonymous, and like cash, it is used by criminals, but not exclusively.

Such misunderstandings are unhelpful, and dangerous from a law enforcement perspective. To focus on Bitcoin and ignore privacy coins, such as Monero, Zcash and Dash, means missed opportunities for law enforcement when conducting investigations and seizing the assets of criminals in searches.

Even with some knowledge about virtual currencies, law enforcement can miss opportunities for seizure and expose virtual assets seized to loss as in the case of the first seizure of bitcoins in Canada in 2014 as explained below.

During the search of an online drug and firearms dealer in Toronto, the suspect informed the police officer that he had transacted in bitcoins, and provided the details of his web wallet and keys. The quick-thinking officer opened a wallet on his own phone and transferred the bitcoins to his mobile wallet from the suspect’s web wallet on his computer. Subsequently, the police opened a wallet on an online exchange where they transferred the custody of the coins from the officer’s phone and where the 288 seized coins currently remain. When seized, the coins were worth $88,000; today they are worth $3.2 million, as legal wrangling continues concerning issues of paying legal fees.

Similarly, in March 2017, Toronto police seized $30,000 in bitcoins and transferred them to an online exchange wallet. Both seizures remain on “hot” wallets, vulnerable to being stolen by hackers or others depending on how secure the private keys are stored. This is not good practice.

These two examples demonstrate the need to raise awareness of virtual currencies within law enforcement generally, but also with those charged with the custody of seized assets and with the prosecution of criminal charges.

Recently, when discussing the results of a search in a fraud investigation with a police officer (it was known the suspects moved their illicit funds using virtual currency), it was learned that false identity documents were discovered together with computers and smartphones.

When asked if virtual currency wallets had been found on the devices, the officer said that the results from forensics would take months to be known. The officer was unaware of deterministic wallets, (that can be recreated typically using a 12 or 24-word back-up phrase or word sequence), and the likelihood that any virtual funds that did exist would be long gone by the time the forensic report was received, (i.e., a missed opportunity).

Despite increasing requests from law enforcement to receive training on virtual currencies from municipal, provincial and federal agencies, many in law enforcement (at least in Canada) have a limited knowledge of virtual currency. The purpose of this article is to provide practical information to law enforcement colleagues that can be used immediately and to build a foundation to learn more.

Virtual Currency Basics

Virtual currencies exist as data entries on, in the case of Bitcoin, a publicly accessible online database called a blockchain. The entries (records of transactions in blocks, similar to each page of a traditional ledger) are secured using cryptography meaning that the entries are extremely difficult to change.

In the case of Bitcoin, the transaction records include the amount (in bitcoins), and the Bitcoin address they were received from, sent to and currently remain. Therefore, Bitcoin transactions are not anonymous. However, the ownership of the wallets is anonymous, at least publicly; hence the term pseudonymous.

Wallets created through an exchange, for example, will often require supporting identity documentation, such as a copy of a driver’s license, passport or utility bill, and many exchange wallets are linked to real bank accounts, credit or debit cards. Depending on the jurisdiction, this information may be available to law enforcement upon service of a warrant, production order or subpoena.

Wallets, which hold the public and private keys required to receive and spend bitcoins (or other virtual currencies), are available on different platforms, including desktops, web wallets (hosted by an exchange of external provider), mobile wallets (on a smartphone), paper wallets and hardware wallets.

As previously mentioned, regardless of the type of wallet, if the wallet can be recreated using a backup seed, then wallets seized by law enforcement are at risk of having their funds transferred out of law enforcement’s reach.

Wallets

Web, desktop and smartphone wallets either require the user to download an app or login to the website of the wallet provider. Some common apps are Mycelium and Bitcoin wallet. Online wallets may appear on a suspect’s desktop or under favorites on their computer, so during searches law enforcement should be aware of these.

Various types of wallets exist—some are designed to transact solely in bitcoins and others in multiple currencies. Some wallets, such as Jaxx, allow conversion between one virtual currency to another, (e.g., Bitcoin to Litecoin) within the wallet’s app. A list of the various types of wallets can be found on bitcoinwiki.1

In addition to wallets law enforcement may encounter on electronic devices, officers should also be looking for hardware wallets, which often have the appearance of a USB stick. Examples of hardware wallets include Ledger Nano wallets, TREZOR wallets and KeepKey wallets.

Hardware wallets allow their owners to keep their virtual currency holdings offline. If the physical wallet is lost, becomes defective or is seized by law enforcement, a new wallet can be ordered and recreated using the backup seed.

Hardware wallets are ideally suited for use by law enforcement when conducting searches and seizing virtual currencies as long as the appropriate safeguards are in place to prevent unauthorized access to the wallet (and its backup seed).

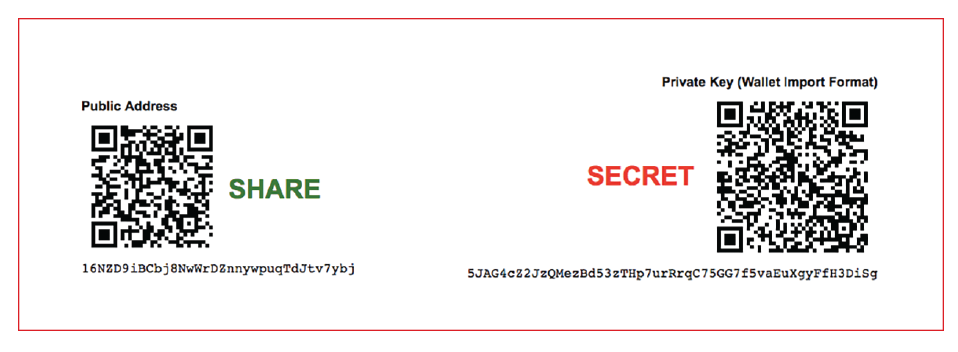

Similarly, law enforcement should be alert to the existence of paper wallets, literally a piece of paper on which is printed the wallet address (to receive virtual currency) and the private key, which is used to spend or transfer the wallet contents. An example of a paper wallet is shown below:

In reality, the writing on the wallet shown is not actually required. Merely keeping a copy of the two QR scan codes will suffice to be able to access any available funds associated with the public address.

Astute readers may realize that a paper wallet performs the same function as a bearer share, identified many years ago as being a money laundering risk. The person in possession of the paper owns the shares, or in this example, the virtual currency.

Technology

As history has demonstrated, lawmakers are always playing catch-up. Technology presents possibly the best example of how quickly and significantly, our laws tend to lag behind. How law enforcement has dealt with new and emerging technologies and has remained constant. As criminals utilize technologies to commit crimes, officers try to keep up the pace by “making the best decision possible.” Without a solid platform of law upon which to base their actions, officers are left “doing the right thing for the right reasons” as in the case of the first bitcoin seizure in Toronto. Such investigative decisions are then scrutinized for years through the levels of the courts, until eventually some direction or guidance is provided through case law.

Thinking back to the not-so-distant past, cell phones presented (and now smartphones still present) a challenge for law enforcement (e.g., to retrieve data or gain access to the encrypted contents).

In the early years of cell phones (the 1970s), officers would routinely search the content of an arrested individual’s cell phone, document any evidence found therein and utilize that evidence as they saw fit. But it took 40 years in Canada for guidance on the search and seizure of cell phones in the form of a landmark ruling by the Canadian Supreme Court, R v. Fearon.2

R v. Fearon laid out four specific criteria that would allow for a warrantless search of a cell phone. If the seizure did not fall within those specific criteria, judicial authorization was required to conduct such a search.

Virtual currencies represent the new technology challenges for law enforcement. Criminal statutes (and law enforcement procedures) in this space lag behind the technology and its use by criminals, with the result that officers are utilizing the “make the best decision possible” approach to seizing virtual currencies. At a minimum, the key to “making the best decision” is to have a working understanding of virtual currencies, what they look like and what they represent.

Any officer seeking to seize virtual currencies will have to answer a number of questions:

- Is virtual currency money?

- Do they fall within the definition of property?

- Does the ability to seek judicial authorization to seize proceeds of crime include virtual currencies?

- Is there any avenue to actually seize a virtual wallet?

- What form should the management of seized virtual currencies take?

Are virtual currencies money?

Canadian laws were not written with a view to seizing and forfeiting virtual currencies. There is currently no predominate legal definition of money that includes virtual currencies. However, a recent court ruling may provide law enforcement guidance, at least in the U.S. In May 2017, Florida incorporated virtual currencies into the Florida Money Laundering Act. The lawmakers classified virtual currencies as a “monetary instrument” and further defined it as a “medium of exchange in electronic or digital format that is not a coin or currency of the United States or any other country.”3

Japan passed the Virtual Currency Act in March 2017. The act recognized virtual currencies as a form of payment method but fell short of recognizing it as a legally recognized currency or legal tender.

Although these acts are not binding outside of their specific jurisdictions, they may provide some guidance to law enforcement officers who are attempting to justify the seizure of or obtain a warrant for the seizure of virtual currencies.

Can cryptocurrencies be considered proceeds of crime?

In Canada, proceeds of crime is defined as “Any property benefit or advantage obtained directly or indirectly”4 by the commission of a for-profit serious offense. Given the broad definition of a “proceed of crime,” in the Canadian context an educated argument could be made to justify the seizing of virtual currencies as such.

Do the conventional methods of seizing the proceeds of crime fit?

Most common law jurisdictions have similar search and seizure laws. When seizing personal (tangible) property, law enforcement typically requires obtaining judicial authorization prior to seizing assets as proceeds of crime. There are certain exceptions to this rule but the general rule of law is that all seizures require judicial oversight. When seizing “real” (intangible) property, the need to obtain prior judicial authorization is even greater. A large number of financial institutions will not freeze accounts and land registry offices will not register a restraint without judicial authorization.

The fact that virtual currencies wallets can be found in several different mediums, such as online wallets, USB keys and even paper wallets, presents an even bigger challenge to law enforcement’s ability to seize virtual currencies.

Crossing international borders in “possession” of virtual currency is a developing challenge for law enforcement and customs officers. Bill S.1241 currently before the U.S. Senate5 seeks to criminalize concealed bitcoin ownership (i.e., undeclared bitcoin or other virtual currencies).

Asset Management

There is a saying in law enforcement that says: “If it has to be fed, don’t seize it!” Although this saying is not entirely accurate, it does serve as a useful reminder to officers that the responsibility of managing, storing or in some cases feeding seized property lies with the state. Given the volatile nature of virtual currencies, having sound policies in place surrounding the management of them is therefore essential. The fact that the seized bitcoins remain on a hot exchange wallet liable to be hacked, is troubling.

It is important to remember that at the time of seizure, the accused has not been found guilty nor has there been a forfeiture order for the seized “property.” As such, it is incumbent on the state to manage that property effectively to ensure it does not depreciate.

At the time of the Toronto seizure, the

value of the bitcoins was approximately CA$88,000; given the current price of Bitcoin, the decision to not convert the coins to fiat currency appears a sound one. But what if the seizure had taken place on December 17, 2017, when Bitcoin was at an all-time high? What if in September 2018, all the charges against the accused are dropped and the bitcoins are ordered to be returned; is the state now liable for the change in value since the seizure?

If a prosecution is successful, and the seized virtual assets are ordered by a court to be liquidated, what is the process to do that? The U.S. provides recent precedent in the auction of 3,813 bitcoins by the U.S. Marshals Service in January 2018.6 The Bulgarian government, who holds more than 200,000 bitcoins seized as the proceeds

of crime, may wish to follow the U.S. precedent, seeing as how these bitcoin are valued in the billions of dollars.7 Hopefully, they are not still sitting on an exchange!

Legal Costs

In Canada, accused persons can apply to use the seized proceeds of crime to pay for a legal defense. This begs the question as to whether accused persons can apply for seized virtual currencies to be used in the same way to pay for their legal defense. Under current Canadian law, the legal answer from most learned Crown Counsel would be “No!” However, applications can still be made and judiciary, who are looking to update laws, have the ability to rule as they see fit.

If a court directs that seized virtual currency can be used to pay legal costs, questions will arise about whether the full amount of currency is converted to fiat, or just enough to pay for the legal costs.

However, current Canadian legislation does allow an order forcing an accused to pay back proceeds of crime that have been used to fund a legal defense. Under the Fine In Lieu of Forfeiture provisions of the Canadian Criminal Code the accused, upon conviction, can be ordered to pay back monies (i.e., virtual currencies) that have been used to pay their defense bill; this of course begs the questions, “In fiat or virtual currency, and what if the price of virtual currency had dropped or risen over the period?”

Articulation

Law enforcement’s ability to articulate the rationale behind their course of action is critical and can make or break a case. The expectation of our law enforcement officers is that they are better educated now than at any time in history. It is reasonable to assume that most seizures of virtual currencies will occur during a search incident to arrest or under exigent circumstances. Search incidents to arrest or exigent circumstances seizures demand strong and clear articulable grounds.

Any officer who has an expectation to seize virtual currencies in relation to exigent circumstances needs to have a working understanding of such currencies. Law enforcement does not need to be experts in hashing, nodes and miners, but they should be expected to have a good understanding of how virtual currencies are transferred and how they can be stored, if they expect to have any success in seizure and subsequent forfeiture.

As was the case when cell phones were first introduced in 1970s education, emerging technologies is, and always will be, law enforcement’s best friend.

Summary

The bottom line for law enforcement is that they cannot seize virtual currency if they do not recognize it and do not know where to look. Even if evidence of virtual currency is found, unless law enforcement is equipped with the knowledge and the tools to take secure possession of it, then it will not happen and criminals will keep their ill-gotten gains.

Knowledge comes from education and associations, such as the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists, who can assist with this and play an important part in protecting the financial system, albeit in the “virtual space.”

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as reflecting those of their employers. In addition, the knowledge contained in this article was obtained by Dwayne King outside of his role with TD Bank Group.

To learn more about how to understand virtual currencies and blockchain technology and how to mitigate the risks, please visit: http://www.acams.org/virtual-currency-and-blockchain-training/.

- “Cryptocurrency wallets list,” bitcoin wiki, February 23, 2018, https://en.bitcoinwiki.org/wiki/Cryptocurrency_wallets_list

- R v. Fearon, 2014 SCC 77, [2014] S.C.R. 621.

- Brad Gershel and Marjorie J. Peerce, “Florida Lawmakers Seek to Bring Virtual Currency into the Fold,” Money Laundering Watch, April 25, 2017, https://www.moneylaunderingwatchblog.com/2017/04/florida-lawmakers-seek-bring-virtual-currency-fold/

- The definition on the Canadian Criminal code speak to indictable offenses, but for the purpose of this article the wording “for profit serious offense” is more effective.

- Landon Mutch, “U.S. Senate Bill S.1241 to Criminalize Concealed Ownership of Bitcoin,” BTCMANAGER, December 1, 2017, https://btcmanager.com/us-senate-bill-s-1241-criminalize-concealed-ownership-bitcoin/

- “For Sale Approximately 3,813.0481965 Bitcoins,” U.S. Marshals Service, https://www.usmarshals.gov/assets/2018/bitcoinauction/

- Nikhilesh De, “The Bulgarian Government Is Sitting on $3 Billion in Bitcoin,” CoinDesk, December, 1, 2017, https://www.coindesk.com/bulgarian-government-sitting-3-billion-bitcoin