In the midst of uproar and hot-button debates over historical slavery in the U.S., virtually none of the discourse calls attention to the fact that slavery continues around the world in the form of human trafficking. In June 2020, Wilhan Martono was arrested in northern California for allegedly operating a $21 million human trafficking business.1 While the more heinous aspects of Martono’s activities include the trafficking of children, he attempted to cover his tracks through judicious money laundering activities. First, buyers paid in bitcoin or prepaid cards, then funds were layered through wire transfers before finally being integrated into bank accounts and stocks of hard silver bullion.2 According to a 2019 report by the U.S. Department of State, approximately 25 million people worldwide live in a condition of slavery as the result of human trafficking.3 For perspective, this is over twice the current populations of Greece or Portugal. Fortunately, the tools of combating one evil are often useful in countering another. In the case of human trafficking, laws against terrorism offer a viable path forward to curtailing its profitability and assisting victims with rebuilding their lives.

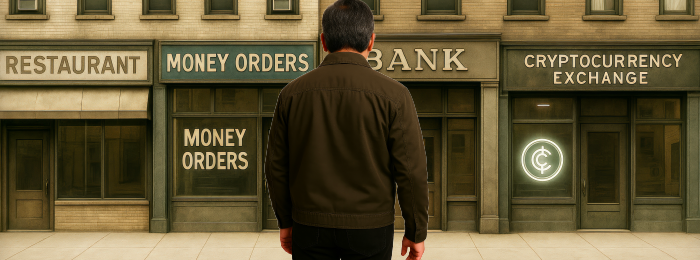

While the actual laundering of human trafficking profits, like those of any predicate crime, can be layered through numerous avenues, the ultimate resting place of the resulting wealth is the banking sector. Banks offer a level of efficiency and liquidity that is unavailable when wealth is encapsulated in some other form. Like the case of Martono, most money derived from crime inevitably becomes reintegrated into the financial system by entering a bank. Legislation designed to combat terrorist financing by opening banks to civil liability can be replicated to combat human trafficking.

After 9/11, legislation and regulation was designed to cut off the funding from terrorism proliferated around the world, while civil “lawfare” in U.S. courts empowered victims of terrorism to sue banks or other corporate entities that were involved in terrorist financing. Two laws in particular, the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) and the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), offer clear pathways for victims seeking restitution.

The ATA serves as the basis for several high-profile civil suits in U.S. courts. Over the first two decades of the new millennium, a number of high-profile cases were brought by terror victims and their families against banks Arab Bank, BLOM Bank, National Westminster Bank and Crédit Lyonnais for allegedly facilitating the financing of the Palestinian terrorist group Hamas.4 It is also worth noting that the ATA’s reach goes beyond banks and financial institutions (FIs) to other types of businesses. For example, the families of missionaries in Colombia who were murdered by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a left-wing drug trafficking organization, filed a federal suit against the fruit company Chiquita Brands International for the company’s alleged material support of the terrorist group.5 Such cases provide an inspiring parallel for potential legislation to incentivize FIs to put controls in place that would make it more difficult for traffickers to integrate their illicit proceeds into the legitimate global economy.

The language of the ATA is very clear in its provision of civil liabilities to economic entities involved in terrorism and in offering a path for victims to obtain monetary compensation. Compared to most statutes designed to combat human trafficking, laws such as the ATA are notably aggressive in enabling victims to seek damages in civil court from third-party entities. Key legislation against human trafficking, such as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act and its subsequent amendments, do not have the same approach as the ATA. The conceptual difference between terrorism and human trafficking is one of the reasons for this dissonance.

Conceptual Differences Between Terrorism and Human Trafficking

Terrorist financing is similar to money laundering in that both activities seek to distance and obfuscate the origins of funds from their end user. A criminal who is not a terrorist must obfuscate the resulting proceeds from the predicate crime that they committed. Thus, when laundering is added to criminal charges, it provides an additional avenue of prosecution and means by which to secure a conviction. In contrast, terrorist financing may often involve funds that are legally or illegally obtained through the conduct of normal business or fundraising but are destined to support an illegal outcome. Laws designed to combat terrorist financing are meant to prevent terrorism as a future crime. Despite the heinous nature of human trafficking, it is still legislatively treated as a crime that has already occurred rather than one that must be prevented.

Human trafficking carries greater operational costs due to the need to keep victims healthy, fed, and constantly guarded or intimidated

Human trafficking comprises an economic activity and a rather costly one when compared to other illicit trades such as black-market antiquities, drugs or arms dealing. Unlike nonhuman contraband, human trafficking carries greater operational costs due to the need to keep victims healthy, fed, and constantly guarded or intimidated. Such activities are incredibly expensive for traffickers, so one key to curtailing systematic trafficking is to attack its economic viability by raising its cost of business. More complicated and costly operations require more funds, while the use of such funds requires more laundering. Enabling victims to file civil suits against banks and other going concerns involved in their trafficking can be accomplished by passing legislation modeled on the ATA. Such legislation would raise the costs of the human trafficking business, and disincentivize criminals from entering into it.

One key difference between the ATA and U.S. laws to combat human trafficking is that the former makes third parties culpable in the economic activity leading to terrorism, while the latter does not. Sections 108 and 109 of the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act of 2015 opens “buyers” of trafficking victims to prosecution, but not third parties such as banks or other entities involved in the transaction. A terrorist group can only operate by using third parties such as banks, transportation firms, telecommunications and other businesses that make their activities viable. Similarly, human trafficking on any significant scale must rely on more tertiary actors beyond the dyad of trafficker and buyer.

Human trafficking is already immoral; however, making it unprofitable and increasing its risk is the key to ending the practice

In the case of Chiquita and the FARC, the company provided the terrorist organization with monthly cash payments6 and weapons.7 While federal law through the ATA allows for victims and their families to pursue damages from third parties with a firm legal grounding, the same solid legal basis does not exist for human trafficking victims. Recently, major hotel chains such as Wyndham, Marriott and Hilton became the targets of lawsuits brought by human trafficking victims.8 Logistically, major hotel chains―especially in locales close to international borders or tourist locations―constitute a critical element of the human trafficking enterprise. The state of Florida passed legislation mandating training for the hospitality industry to assist in spotting trafficking.9 Such anti-trafficking mandates are similar to the mandatory compliance standards imposed on the financial industry as it pertains to terrorist financing. However, unlike the ATA, third parties are not statutorily culpable for civil liabilities.

Conclusion

Anti-human trafficking groups could easily draw from the ATA and other counter-terrorist financing laws to develop proposed legislation designed to hold banks and other third-party businesses accountable. Politically, few elected officials would object to combating human trafficking and legislation can easily be proposed at the state and federal levels. The financial costs of conducting trafficking would dramatically increase if traffickers were forced to seek alternatives to formal banks and invest in different properties rather than relying upon the hotel industry. Human trafficking is already immoral; however, making it unprofitable and increasing its risk is the key to ending the practice. While demand for trafficking will never entirely disappear, the profit margins of the crime can be substantially reduced as costs increase. Creating risk for secondary and tertiary actors, aside from the traffickers themselves, imposes more costs on traffickers as they will be forced to operate more aspects of the business directly. Holding third parties liable through civil cases and having such suits grounded in statute offer a viable path forward to creating these costs.

Dr. Ian Oxnevad, consultant, editor@acams.org

- Nate Gartrell, “Bay Area man made $21 million operating international sex trafficking websites that included child victims, feds say,” The Mercury News, June 18, 2020, https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/06/18/bay-area-man-made-21-million-operating-international-sex-trafficking-websites-that-included-child-trafficking-victims-feds-say/(accessed June 29, 2020).

- Ibid.

- “2019 Trafficking in Persons Report,” U.S. Department of State, June 2019, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Trafficking-in-Persons-Report.pdf (accessed June 29, 2020).

- “Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA),” Osen LLC, https://www.osenlaw.com/practice-areas/anti-terrorism-act-ata, (accessed July 6, 2020).

- Chiquita Case, Osen LLC, https://www.osenlaw.com/case/chiquita-case (accessed July 6, 2020).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Corinne Ramey, “Lawsuits Accuse Big Hotel Chains of Allowing Sex Trafficking,” The Wall Street Journal, March 4, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/lawsuits-accuse-big-hotel-chains-of-allowing-sex-trafficking-11583317800, (accessed July 6, 2020).

- “CS/CS/CS/HB 851 ― Human Trafficking,” Florida Senate, https://www.flsenate.gov/PublishedContent/Session/2019/BillSummary/Criminal_CJ0851cj_0851.pdf, accessed July 6, 2020.

This is a very interesting and valuable article; however when I saw the heading I was looking forward to an expose on tools that can be used by FIs in the detection of and fight against human trafficking.