Trafficking—of blood diamonds, endangered wildlife or even humans—has garnered fierce international engagement in recent years. One under-addressed illicit trade is that of art and antiquities. While ancient art and antiquities can serve as sound investments, such acquisitions can also support nefarious activity and compromise consumers.

Cultural racketeering—the looting and trafficking of art and antiquities—funds crime, conflict and extremism around the world. Art and antiquities have financed some of the last century’s worst actors from drug cartels and mafia syndicates to the Nazis, the Khmer Rouge and al-Qaeda, and cases of looted and trafficked antiquities continue to make headlines across the world. In cases of sanctioned individuals seeking access to U.S. financial institutions or criminals seeking funds for illicit activities, art can also be a conduit through which to launder money. This is a global problem, and it requires global solutions.

Current and Recent Cases

As the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has warned, art and antiquities are particularly vulnerable to money laundering and terrorist financing, which often go hand-in-hand. Yet, regulatory mechanisms to close U.S. borders to blood antiquities and enhance transparency in art markets remain far too weak, as demonstrated by several high-profile criminal cases in the art market. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) is currently investigating a $50 million money laundering scheme involving a single Picasso painting. Yves Bouvier, the famed Swiss art dealer, has repeatedly been investigated and indicted on charges, including money laundering, around the world—from Singapore and Monaco to the U.S.

In Operation Mummy’s Curse, a joint U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement/ U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York (EDNY) case, Mousa Khouli and his co-defendants were indicted for eight criminal counts. One count included a money laundering conspiracy touching the U.S., U.K. and United Arab Emirates, violating §18 U.S.C. 1956, one of the key American money laundering statutes. Khouli ultimately accepted a plea deal and forfeited millions of dollars’ worth of antiquities, which included $2.5 million of Egyptian pieces and roughly $80,000 in cash. Cases like these underscore the often shadowy world of international art markets and the sizable price tags that accompany these crimes.

Why Fight the Antiquities Trade

The Antiquities Coalition was founded in the wake of the Arab Spring, which saw wholesale destruction of cultural heritage throughout the cradle of civilization. We were inspired by the group of Egyptians who protected the Egyptian Museum during the 2011 revolution. Following the revolution, there were reports of mass looting at some of the country’s most famous archaeological sites. Having founded an archaeological institute at George Washington University, the Egyptian Minister of Antiquities at the time, Zawi Hawass, helped launch the Antiquities Coalition.

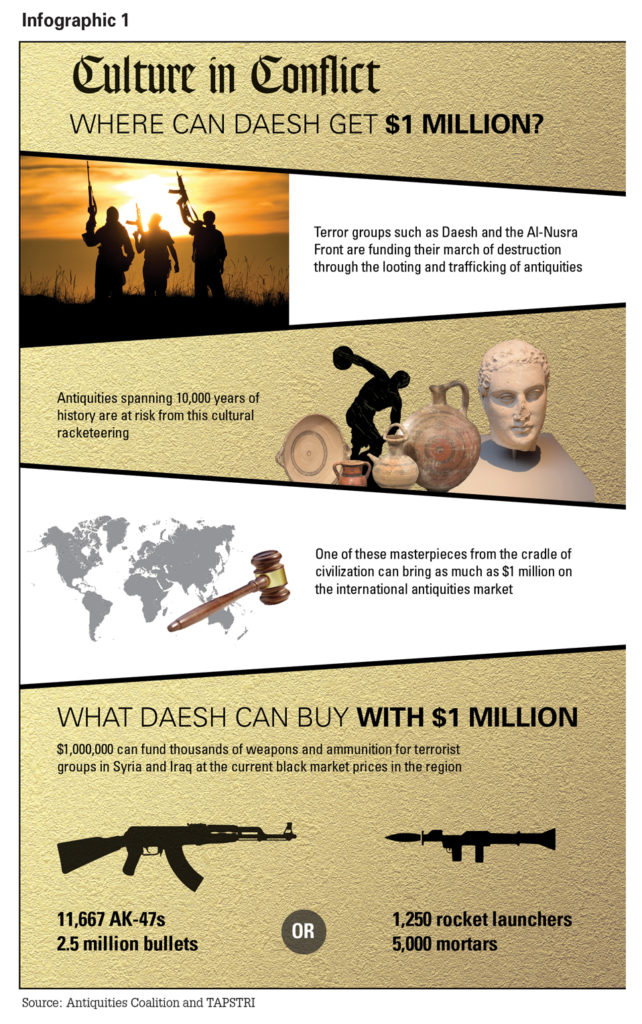

More recently, groups like Daesh (Islamic State [IS]), al-Qaida, the Taliban and their affiliates have been engaged in cultural racketeering and terrorism in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan and elsewhere, converting patrimony into cash for weapons and troops. Their atrocities prolong instability and weaken peace for future generations. Daesh has razed entire temples at the ruins of Palmyra in Syria and Nimrud in Iraq, dynamited the Judeo-Christian Tomb of Jonah and the Sunni mosque of the Prophet Yunnis, pillaged the Mosul Museum, and obliterated countless Shiite and Sufi places of worship.1 Throughout the region, antiquities are an almost endless resource.

For perspective, Daesh had a ministry of extraction whose primary resources to oversee were petroleum and antiquities. But Daesh is not alone. From Egypt and Libya to Yemen, cultural crimes have proliferated in the vacuum of political instability and breakdown of security following the 2011 Arab Spring. These attacks are funding conflict and crime, creating long-lasting economic damage and undermining future peace.2 In some cases, cultural crimes can serve as a warning of impending genocide. In other cases, cultural crimes themselves can constitute war crimes or crimes against humanity.

The rise of the internet has further compounded the growth in cultural racketeering since the internet has enhanced global communication and the ability to move objects quickly. Terrorist groups are able to exploit existing distribution channels to launder money, acquire arms and extend their violent campaigns. For example, a route for bootlegged DVDs or narcotics one day can easily become a distribution path for trafficked antiquities the next. The efficient distribution patterns of organized crime and the rise of terrorism, combined with the breakdown of civil society in places like the Middle East, has resulted in an illicit trade of antiquities on an industrial scale. Yet, the path to mainstream markets often takes years. As objects begin to appear in markets in the West or in Asia—two of the biggest centers of demand for antiquities—professionals begin to better ascertain what exactly has been looted and by whom.

The Illicit Antiquities Trade and Terrorist Financing

Illicit antiquities fund terrorism both in conflict zones and in the West. The 2016 attack in Brussels was linked to cultural racketeering through suicide bomber Khalid El Bakraoui. In these such attacks, just a few antiquities can provide funding for a large cache of weapons. For example, the cost of the November 2015 attacks in Paris totaled just $88,160, including telephones, false identification, travel and other costs. In that one attack alone, the cost of false identification amounted to $5,370—the cost of a relatively inexpensive antiquity.

Infographic 1 illustrates concerning facts about the illicit antiquities trade and its links to terrorist activity. The ten countries with the most terrorist activity export antiquities to the U.S., and the post-Arab Spring years have witnessed a substantial increase in U.S. imports of cultural property. Between 2011 and 2016, declared imports of art and antiquities increased over $9 million annually from these countries, amounting to an overall increase of 48.1 percent growth. The FBI has also recognized the credibility of reports that artifacts looted to fund violent extremism are heading for the U.S. art market.3

Inadequate Regulatory Mechanisms Facilitate This Illicit Trade

The scale of the art market itself lends itself to regulation, and yet it is hardly regulated. The U.S. remains the world’s largest art market, valued at $26.6 billion, and accounts for 42 percent of the global total in 2017.4 In Europe, the art and antiquities market accounts for nearly $23 billion annually.5 While the U.S. and Europe are the world’s top two art consumers, China is fast approaching.

The market itself has increasingly recognized its own vulnerability to financial crimes. The Basel Art Trade Guidelines warn that, “In comparison with other trade sectors, the art market faces a higher risk of exposure to dubious trade practices” including antiquities trafficking, fraud and money laundering. They attribute this to “the volume of illegal or legally questionable transactions, which is noticeably higher in this sector than in other globally active markets.”6

Amid mounting criminal cases in the art world, intergovernmental bodies are increasingly becoming aware of the linkages between the illicit antiquities trade and terrorism. The U.N. Security Council in December 2014 recognized the link between smuggling of artifacts and terrorist financing in Resolution 2195, providing a strong incentive for the international community to act against this problem.7

In addition to growing willingness from art markets to address criminal activity in the shadows of global markets, the tide may also be turning in the U.S. In response to concerns of the growing illicit trade, early this year the Manhattan district attorney’s (DA) office announced the establishment of an antiquities trafficking unit that “formalizes the collaborative processes and partnerships that led to these successful recoveries,” referencing the DA’s seizure of more than $150 million in illicit antiquities.

However, the U.S. remains significantly behind in terms of agencies qualified to address these issues as well as legislation aimed at stemming criminal activity in art markets. For example, the U.S. does not even have a ministry or department of culture as do most other countries. Achieving headway in money laundering and art markets requires diligent work across the Department of State, Department of Defense, DOJ, Congress and law enforcement agencies, in combination with an increase in targeted legislation.

The U.S. is also behind legislatively. The Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network already requires dealers in precious metals, stones, and jewels to establish anti-money laundering programs. Federal law also demands the same from sellers of automobiles, planes and boats; casinos; pawnbrokers; real estate professionals; and travel agencies. Yet the art world, where a single transaction could be hundreds of millions of dollars, remains exempt from standard legal obligations.8

One fundamental art market loophole is that, unlike other financial institutions, the art market is not currently subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)

One fundamental art market loophole is that, unlike other financial institutions, the art market is not currently subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). The BSA requires “financial institutions” to assist the U.S. government in detecting and preventing money laundering, terrorist financing and related crimes. The art market clearly meets the BSA’s definitions of a financial institution—that is a business “whose cash transactions have a high degree of usefulness in criminal...matters.” This is evidenced by the DOJ’s ongoing prosecution of six individuals and four corporations for a $50 million dollar money laundering scheme involving a Pablo Picasso painting. One of the defendants told an undercover agent they had originally planned to clean their funds through real estate, but turned to art because it is “the only market that is unregulated.” Such regulation is especially needed since the U.S. remains the world’s largest such market, valued at a staggering $26.6 billion and accounting for 42 percent of the global total in 2017.9

Moreover, an estimated 3–5 percent of the global GDP is laundered each year, totaling some $2.17–$3.61 trillion. As post 9/11 reforms have increasingly closed the formal financial sector to violent extremist organizations, they have turned back to “traditional ways such as…money laundering… to move their funds to finance their terrorist activities.” The Illicit Art and Antiquities Trafficking Prevention Act (H.R. 5886), currently in the House, proposes amending the BSA to address some of the opaque areas of the art trade.10

The proposed legislation would end the art market’s exemption from otherwise standard regulations. While this bill represents progress in the U.S., American legislation on money laundering and the art trade remains less robust than elsewhere. Since the wake of the Panama Papers in 2016, the EU has passed five new regulations aimed at combating money laundering and terrorist financing within international art markets.

In the absence of more robust regulatory mechanisms to address cultural racketeering, buyers, investors and bankers can take steps to enhance due diligence in art markets. As Infographic 2 illustrates, objects often contain strong indications of criminal activity, including originating from a conflict zone, being covered in dirt or having a “too good to be true” price.

Conclusion

At the Antiquities Coalition, we know the fight against this illicit trade must cross borders and disciplines. Since the organization’s beginning, a key priority has been shutting the U.S. market to illicit antiquities, while encouraging responsible trade practices.

For more information on how to identify and mitigate terrorist financing, please visit: http://www.acams.org/counter-terrorist-financing-training/.

- “#CultureUnderThreat Task Force,” The Antiquities Coalition, http://taskforce.theantiquitiescoalition.org/

- Ibid.

- “ISIL and Antiquities Trafficking: FBI Warns Dealers, Collectors About Terrorist Loot,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 26, 2015, https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/isil-and-antiquities-trafficking

- Dr. Clare McAndrew, “The Art Market 2018:An Art Basel & UBS Report,” Art Basel & UBS, 2018,

https://d2u3kfwd92fzu7.cloudfront.net/Art%20Basel%20and%20UBS_The%20Art%20Market_2018.pdf - “Security Union: Cracking down on the illegal import of cultural goods used to finance terrorism,” European Commission, July 13, 2018, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1932_en.htm

- “Letter of Support for H.R. 1493/S. 1887,” The Antiquities Coalition, May 30, 2018, https://theantiquitiescoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2018-05-30-Antiquities-Coalition-Letter-in-Support-of-Art-BSA-1.pdf

- “Security Council, Adopting Resolution 2195 (2014), Urges International Action to Break Lines between Terrorists, Transnational Organized Crime,” United Nations, December 19, 2014, https://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11717.doc.htm

- “Letter of Support for H.R. 1493/S. 1887,” The Antiquities Coalition, May 30, 2018, https://theantiquitiescoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/2018-05-30-Antiquities-Coalition-Letter-in-Support-of-Art-BSA-1.pdf

- Ibid.

- “H.R.5886 - Illicit Art and Antiquities Trafficking Prevention Act,” Congress.gov, May 18, 2018, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5886/text

Very informative read. Personally i am baffled that even in the US – the front runner in the fight against financial crime- the art and antiquities industry are left unregulated from AML/CFT perspective. Glad that there is a WIP bill.