Editor’s note: This article is the second of a three-part series on child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and child sex trafficking (CST). The first part is available here.

***Disclaimer/trigger warning: This article discusses sexual offenses committed against children. Reader discretion is advised.

What is sextortion?

Sextortion is a form of online extortion that involves the threat of distributing intimate or sexually explicit images or videos of a victim unless they comply with the demands of the blackmailer. Intimate content can be obtained by hacking a victim's device or social media accounts or manipulating the victim into a false sense of trust. Once the content has been obtained, they threaten to disseminate it to people in their personal or professional circles or post it publicly on social media or websites. The scammers behind sextortion crimes are often more aggressive than other cyber criminals and although the numbers vary, many follow through on their threats if the victim fails to comply with their demands.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, sextortion crimes have grown at an alarming rate, according to many law enforcement (LE) authorities. As mentioned by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), online child sexual exploitation (OCSE) has increased, likely due to some of the following factors:

- Increased unsupervised internet usage by children during school hours.

- Restricted travel resulting in more sex offenders being online.

- Increased access to and use of technology, including encrypted communications, bulk data transfer, cloud storage, livestreaming and anonymized transactions.1

Furthermore, Statistics Canada reports that “Over the course of the pandemic, the number of cyber-related extortion offences increased up 78% from 2019 to 2020, and 18% from 2020 to 2021.”2 Blueline Magazine (Canada’s official LE magazine) describes sextortion as an “epidemic within a pandemic.”3

Sextortion—Old Versus New and Emerging Trends

Historically, sextortion has been a sexually motivated crime, with the demands being for more intimate content and/or physical sexual encounters, but this has changed. A recent analysis by the National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) stated that 79%4 of reported sextortion crimes are financially motivated.

The financial motive does not make the crime any less insidious. One of the more disturbing new trends has been the targeting of teen males for sextortion schemes, with a growing number resulting in the victim committing suicide. In some cases, the blackmailers attempt to extort the victim’s family by threatening to shame their deceased loved one by distributing their nude content online unless payment is received.

The spike in financially driven sextortion crimes has also given rise to a new and emerging parallel scheme known as a “recovery scam.” In a recovery scam, criminals will often masquerade as hackers, cyber security experts or reputation management firms who will track down and remove intimate content from the internet. Upon paying a fee, no services are rendered, and the images and videos remain online and publicly accessible.

“Cappers”

In October 2012, British Columbia teen Amanda Todd tragically took her life after being entangled in a vicious sextortion scheme for 18 months. Her tormenter, Aydan Cobin, was an adult male from the Netherlands who, in November 2022, was convicted by a Canadian court and sentenced to 11 years in prison. Cobin is known to have had dozens (or more) victims and used a tactic that involved taking screenshots of victims when they are nude or “flashing,” after which the screenshots were used to sextort the victim.5 This tactic is knowing as “capping” and the criminals who use the technique are referred to as “cappers.”

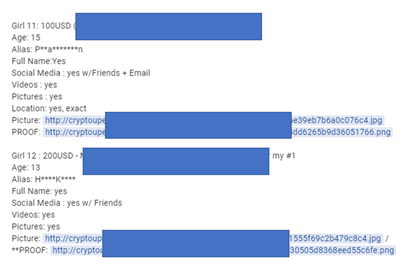

Cappers have vast online forums and communities in which they share tips to find and manipulate victims and how to coerce them into providing degrading and humiliating content. Some even have “awards” for achievements (e.g., Capper of the Month, Best Content). Cappers also buy, sell and trade victims once they grow tired of them. The marketplaces contain detailed directories of available victims (usually minors), which include price, proof of life photos/videos, name, age, gender, physical description, names of family and friends, how complicit/compliant they are, if they have access to other children whom they can include in their content and what sex acts they have done.

A real screenshot from a sextortion dark web marketplace (i.e., for reference):

Sextortion—Cause For Hope

Despite the grim statistics, there is hope. First, with the majority of new sextortion crimes being financially driven, there is ample opportunity for financial investigators to spot transactions and take action. FinCEN observed in suspicious activity report (SAR) filings that criminals are increasingly using CVC (the most common payment method), peer-to-peer mobile applications (e.g., PayPal) and third-party payment processors to conceal illicit file sharing and streaming activities. In addition, there is typically no physical or geographical connection to the victim. Countries such as the Philippines, Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire (The Ivory Coast), Ukraine and Mexico are the most common locations of scammers.

Second, one of the biggest concerns of victims is that their explicit content will always remain available and that their exploitation will continue indefinitely each time someone views the content. NCMEC recently launched its “Take It Down” campaign.6 This new service allows minors to file an online report in which they upload the photos and videos that they want to be removed from the internet. NCMEC’s “Take It Down” platform then scans the internet and reports back with a list of all locations where the content appears so that it can be removed.

If in the course of your investigation you feel additional action is required beyond filing your SAR, the Department of Homeland Security recommends filing a cyber tip report with NCMEC.7 If the matter is urgent (e.g., you feel a child has been or could be abducted or is otherwise at risk of imminent danger), you are encouraged to call the NCMEC helpline at 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678).

Conclusion

We can help prevent sextortion in our families by teaching our children and teens simple things to help safeguard them. One simple tip is to keep devices out of private spaces inside the home (e.g., bedrooms, bathroom) and provide appropriate levels of supervision, as sextortion criminals need unsupervised access to our children for them to appear nude on camera.

Another suggestion is to let our children know that it is okay to make mistakes. If they do, make sure children understand they are believed and are not to be blamed, that they do not need to keep making the same mistake, that you will help them and that they will be safe. This kind of support will go a long way in preventing this crime. Children should be taught to take threats seriously and get help, but never comply with them, as that only makes the situation worse. Speaking about healthy relationships, love, respect and dignity is crucial. They need to know that someone who really cares about them and loves them would never ask them to do anything that makes them feel uncomfortable. As parents (or those caring for children), the need for both open and honest communication, age-appropriate education and supervision are the very best assets we have at our disposal to prevent online exploitation. When prevention fails, financial professionals are in a unique position to notice suspicious financial activity that may be indicative of child sexual exploitation and sex trafficking and file SAR reports for LE to investigate. While it is a lot of hard work, these reports can and do lead to the safe recovery of child victims and apprehension of dangerous child predators and traffickers. We all need to do our part to protect the vulnerable and when we work together we are making our communities safer places for children and families.

Matt Richardson, director of Intelligence and Investigations, Anti-Human Trafficking Intelligence Initiative (ATII), ![]()

Resources

Department of Homeland Security:

https://www.ice.gov/features/sextortion

https://www.dhs.gov/news/2022/04/05/fact-sheet-dhs-efforts-combat-child-exploitation-and-abuse

National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children:

https://www.missingkids.org/theissues/sextortion

https://www.missingkids.org/content/dam/missingkids/pdfs/ncmec-analysis/sextortionfactsheet.pdf

https://takeitdown.ncmec.org/

https://report.cybertip.org/

Thorn:

https://www.thorn.org/sextortion/

- “FinCEN Calls Attention to Online Child Sexual Exploitation Crimes,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, September 16, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FinCEN%20OCSE%20Notice%20508C.pdf

- Greg Moreau, “Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2021,” Statistics Canada, August 2, 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2022001/article/00013-eng.htm

- Isabelle Sauvé, “COVID-19 and sextortion: An epidemic within a pandemic,”BlueLine, March 2, 2023, https://www.blueline.ca/covid-19-and-sextortion-an-epidemic-within-a-pandemic/

- “Sextortion,” National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, https://www.missingkids.org/theissues/sextortion

- Amy Judd, “Dutch man convicted of extorting B.C. teen Amanda Todd returned to the Netherlands,” Global News, November 29, 2022, https://globalnews.ca/news/9313326/dutch-man-aydin-coban-netherlands-amanda-todd-bc-sentence/

- “Take It Down,” National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, https://takeitdown.ncmec.org/

- “Report an incident,” National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, https://report.cybertip.org