The perfect storm of heightened regulatory pressures and sophisticated, high-velocity fraud attacks have created an opportunity for fraud and compliance departments to pool budgets and resources, as well as adopt new technologies to reduce financial and reputational risk exposure. The purpose of this article is to highlight the qualitative and financial justification for merging fraud and anti-money laundering processes toward a financial crimes operating model.

Opening the Lines of Communication

For several years, the financial services industry has debated the merits of converging anti-fraud and AML processes under a financial crimes umbrella. But, more and more, financial institutions are realizing that a holistic view of suspicious customer behavior—across all product lines and services—can translate into more effective and efficient investigations, by improving collaboration between departments, eliminating redundant inquiries and identifying risks that would be missed by disparate processes and tools.

In December 2010, the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists and Ernst & Young published a joint survey of 250 global respondents from financial services, law enforcement and regulatory agencies. The survey—"Linking Anti-fraud and Anti-money Laundering Programs: Unrealized Opportunity or Unnecessary Complexity?"—revealed that 52 percent of financial services firms had already integrated some aspects of their AML and anti-fraud functions. Furthermore, 64 percent of government agencies recommend that financial institutions take a more concerted approach to financial crimes.

The Growing Requirement for Convergence

Several publications have reinforced the case for convergence of financial crimes processes, including: the money laundering and fraud correlation highlighted Mortgage Loan Fraud Connections with Other Financial Crime by the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network; the Wolfsberg Group report on synergies between credit card fraud risks and money laundering, Wolfsberg AML Guidance; and FinCEN's Advisory Guidance to Financial Institutions on Recent Events in Syria that advises enhanced due diligence of politically exposed persons for movement of fraudulent, or misappropriated assets.

According to a report on case management from the Tower Group, a leading research and consulting firm focused on the global financial services industry, "demands for greater visibility and transparency into risks of all forms, new mandates from the boardroom regarding risk reduction, and regulatory requirements that cross over from other parts of the business are all heightening the need for a more holistic approach to managing risk and fraud."1

All of this—as well as an expectation by governments and regulators that fraud investigators know when a suspect is also being investigated elsewhere within an institution—will require financial institutions to move away from working in silos and share resources and processes to better optimize financial crimes detection.

Creative fraudsters often spread their criminal activities across products and transactions, with each activity appearing innocuous. Collectively, such activities represent serious losses that can be prevented with prior knowledge of cases worked elsewhere. With credit, treasury and AML departments, for example, working separately—with their own point solutions to manage and report on cases—little communication happens among teams and there is often a reluctance to share what is viewed as proprietary data.

We recently reviewed a project with an Asian bank that analyzed cross-channel data to detect organized crime rings. In one particular ring, the bank had already identified three of the subjects with their existing fraud alerting systems. When we applied network analytics to include transactions and demographic data, we were able to identify six more individuals that shared a common address, common employer, and common birth dates. When we reviewed their transactions, they were conducting cash, checks, wires, and ATM transactions through ATM and phone channels. They exhibited a variety of fraud and structuring behaviors. In a vacuum, their behavior seemed benign. However when we viewed the ring holistically, there was a half million dollar risk exposure in potential charge offs. In this example, we increased our fraud detection by taking a holistic approach. As a result, the head of group security for the institution had justification to create a new investigation function devoted to organized rings irrespective of a fraud or AML bias.

While the idea of combining anti-money laundering and anti-fraud processes may at first seem like a daunting task, especially for small- to mid-size institutions, it is not necessary to reorganize or merge established departments to gain improvements in efficiency and effectiveness. Much of the data required to detect money laundering is similar to the information required to prevent fraudulent transactions. While the processes and work flow for managing fraud and AML alerts are very different, most institutions are consolidating investigations onto a unified platform to eliminate redundant reviews of subjects. AML professionals should fare well in this operating model given that money laundering investigations often span multiple parties, accounts and products.

Enterprise Case Management

Convergence can be defined as the coordinated movement of two eyes or the merging of distinct technologies. A pragmatic approach is to start first with a "two-eyes" model that uses enterprise case management (ECM) technology to help investigators connect the dots between suspicious behaviors and customers. Once we view illicit behavior for a subject across the enterprise, we gain a more accurate view of fraud exposures and often detect previously hidden customer relationships that could represent significant reputational risk.

By consolidating alerts from myriad sources, ECM systems enable efficient investigations through cross-departmental analysis of transaction data and other account information. With more information available, investigators resolve alerts more quickly. In cases involving more sophisticated typologies, ECM systems enable the investigator to see all fraud and AML alerts for the subject, thus improving the accuracy of decisions. Most financial institutions have already invested in software applications for money laundering and fraud analysis, and, given the current economic climate, it is unpopular to "rip and replace" mature systems. However, the latest generation of ECM systems can consume alerts from disparate systems, apply alert management logic for scoring and handling and provide an enterprise view of risks at the portfolio, geographic, or customer dimension. In essence, new technologies can augment existing systems to deliver marked improvement.

The increase in enforcement actions has increased the importance of governance and audit of investigations to ensure consistent adherence to policies and procedures. Structured work flows provide controls to govern requisite investigative processes. The ability to explain decisions and provide management reporting on trends and summaries is crucial to managing risk across financial crimes exposures. ECM systems provide management reporting and trending of key operational statistics including volume, recoveries, case aging, SAR filings and exposures. In the face of dynamic fraud risks and regulatory expectations, financial institutions will need a system that is extendable, interoperable and highly flexible.

Financial Justification—A Sample Business Case

A financial institution can easily justify the adoption of a financial crimes approach by quantifying cost savings and improved detection rates. In this example, a mid-sized bank holding company wanted to determine the savings and return of implementing an ECM system as the first step in their rollout of an enterprise financial crime platform. During the exercise, we cited numerous financial benefits including system consolidation, reduction of IT staffing costs, as well as reduction of software maintenance fees through elimination of redundant systems. However, the client wanted to focus on the direct benefits to the financial investigation process. In our study we agreed to measure the following benefits:

Improved Investigation Efficiencies

- Increased speed of investigation because the system displays all alerts for a subject to the analyst, eliminates the need for queries to systems of record and automates population of critical fields.

Increased Fraud Detection Rates

- Often, low value events are not recorded and measured as fraud. The system aggregates exposures that previously would not have been captured and measured.

Elimination of Duplicate Effort

- Cost savings due to the elimination of duplicate alert reviews and case investigations of common subjects and elimination of re-keying data.

Improved Reporting and Audit Functions

- Reduction in amount of hours required to generate reports on risk exposures, filings, losses and operational metrics.

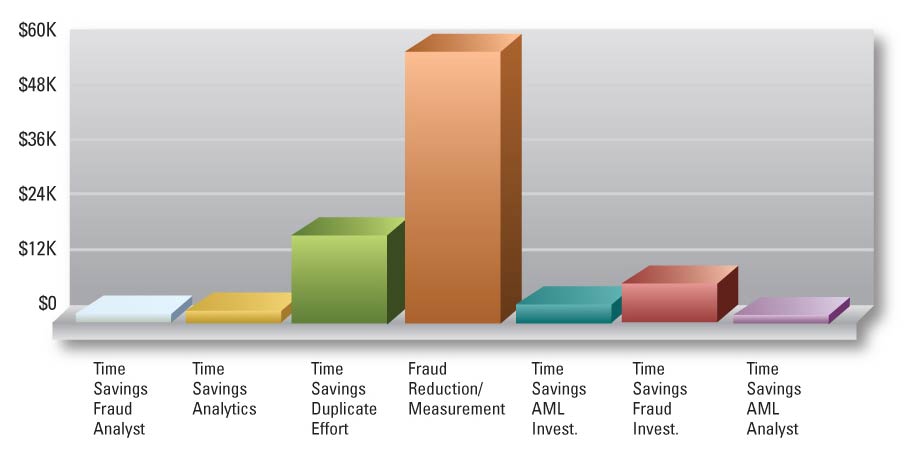

To construct the business case, we measured the annual carrying cost of each of their analysts and investigators; average weekly hours spent on investigations, number of investigations, expected elimination of duplicate work, and expected increase in fraud detected. The following table lists conservative assumptions provided by the client:

| Role | Full Time Equivalent or Employees | Improvement Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| AML Analyst | 3 | 15% |

| Fraud Analyst | 3 | 15% |

| AML Investigator | 5 | 15% |

| Fraud Investigator | 8 | 15% |

| Analysis/Reporting | 3 | 20% |

| Elimination of Duplicate Effort | 22 | 15% |

| Fraud Detection Rates | NA | 10% |

For this Financial Investigations Unit consisting of 19 analysts and investigators, there was significant savings in consolidating their case management processes into an enterprise view. When we aggregated the net effect of expected benefits on a monthly basis, we estimated the system to save nearly $90,000 per month in efficiency gains and more accurate fraud detection measures. As we review the bar charts above, the most significant benefits were identification of new fraud risks and elimination of duplicate work effort.

The Return on Convergence

Financial institutions are being driven to improve efficiencies and become more effective at combating emerging financial crimes risks. Sophisticated criminals and high-risk customers enjoy relative anonymity by exploiting impersonal channels and electronic commerce. Regulatory agencies, trade associations, financial intelligence units and industry best practices recommend a holistic approach to managing investigations.

Financial institutions are being driven to improve efficiencies and become more effective at combating emerging financial crimes risks

Our sample case study demonstrates that there is economic benefit to justifying the investment of an enterprise case management system to integrate AML and fraud processes. Gaining a holistic view of a subject's behavior across the enterprise is a good first step toward a financial crimes operating model.

As industry adoption matures, the integration of cross-channel financial crimes data will be pushed into the detection and alert management functions. The use of technology to execute real-time decisioning at point-of-sale will be crucial with the adoption of mobile banking. The latest generation of ECM systems provide a basis for understanding enterprise financial crimes risks. In effect, "what's my exposure to known events or losses?" Once these exposures can be quantified and accurately measured, institutions will have a much clearer road map of where to invest resources that are aligned with actual financial crimes risk exposure.

- The Tower Group. The Evolution of Case Management: Converging Fraud, Risk, and Opportunity Management, Rodney Nelsestuen. August 2009.