Organized retail crime (ORC) is tempting to transnational criminal organizations due to its low-cost, high-value nature. In the U.S., jails are overcrowded, and instances of theft are becoming increasingly decriminalized; therefore, it can be an attractive revenue stream for criminal organizations.

Defining ORC

ORC is low cost, high reward for transnational criminal organizations. It is, thus, appealing for criminals to conduct ORC activities to further fund other criminal activities, like drug trafficking and human smuggling. Public perception of this billion-dollar criminal activity is to write it off as a bunch of shoplifters and view it as a problem for retailers to solve themselves. However, a common misconception is that this problem is “just shoplifting.” This problem even surpasses the “smash and grab” thefts that get sensationalized in the news, as these are often local gangs or even groups of opportunists taking advantage for a quick gain. ORC is an organized crime that involves professional, organized theft groups (OTGs). These are transnational criminal networks of individuals working together to steal for profit that finances their ongoing operation and other criminal activity.

“Organized retail crime is leading to more brazen and more violent attacks in retail stores throughout the country. Many of the criminal rings orchestrating these thefts are also involved in other serious criminal activity such as human trafficking, narcotics trafficking, weapon trafficking, and more. Tackling this growing threat is important to the safety of store employees, customers, and communities across the country.”

Steve Francis, acting executive associate director, Homeland Security Investigations

According to the Washington Organized Retail Crime Association (WAORCA), ORC is defined as “the Theft/Fraud activity conducted with the intent to convert illegally obtained merchandise, cargo, cash, or cash equivalent into financial gain (no personal use), where/when the following elements are present: occurs over multiple occurrences, and/or in multiple stores, and/or in multiple jurisdictions, conducted by two or more persons or an individual acting in dual roles (booster & fence).”1 ORC syndicates plan attacks on highly sought-after goods and then sell them either through backdoor and online marketplaces or, in many cases, through apparently legitimate business fronts operating in plain sight.

Different from burglary and larceny (i.e., shoplifting) because it is not the result of one person breaking the law, ORC is part of an organized scheme with multiple actors to defraud retailers or steal products for resale elsewhere. Therefore, “organized retail crime syndicates focus on high-value branded items like leather goods, OTC [over-the-counter] medications, health and beauty products, designer clothing and power tools—that are in demand from consumers, most of whom are unaware that they are purchasing stolen goods.”2 It is important to address that ORC is not a victimless crime. As seen on the news, theft can be violent, and sales associates have been threatened with weapons. Many ORC syndicates fund other criminal activities, such as labor, arms and drug trafficking with their ill-gotten gains, in addition to defrauding retailers, threatening employees, reducing choice and increasing consumer costs.

Common retailers targeted by organized theft syndicates include pharmacies, big box retailers, home improvement stores, grocery stores and softlines merchants. The top cities in the U.S. by reported cases include New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, Washington D.C. and Baltimore. In addition to the increased ease of selling, the U.S. has begun raising felony thresholds for theft, essentially decriminalizing the act as jails are becoming overpopulated.3

The Link Between ORC, OTG and Other Nefarious Criminal Activity

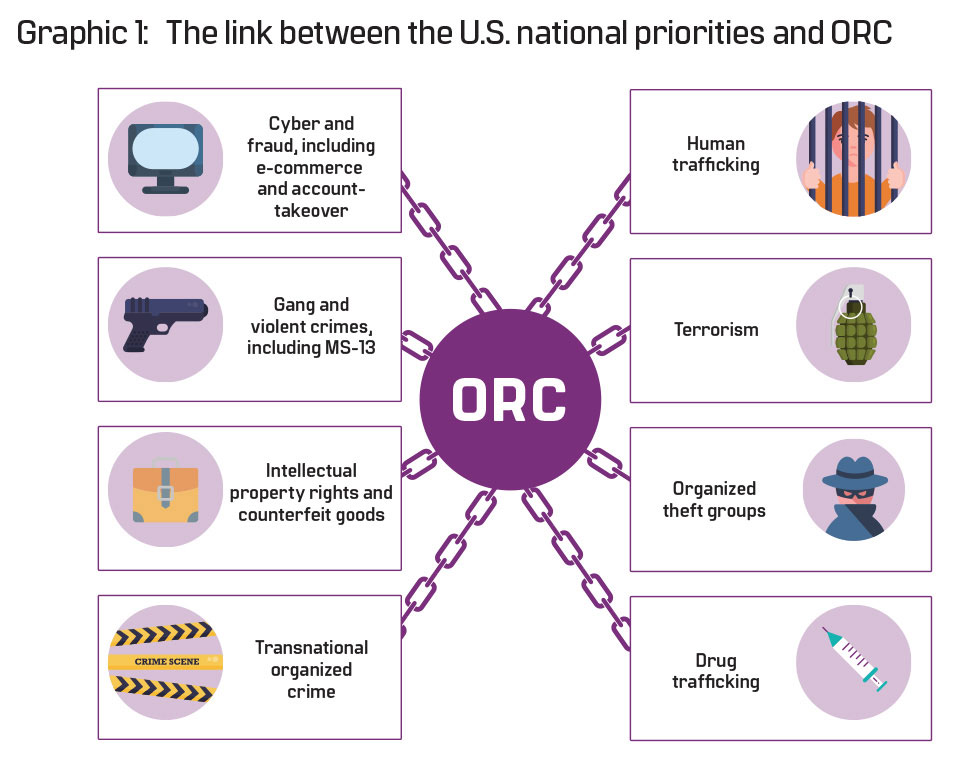

ORC has vast economic costs to the global economy and exploits the formal financial system. In addition to the illicit proceeds touching the global financial system, law enforcement (LE) investigations have proven that in many cases, ORC is related to, and is funding, other criminal activity that is already monitored by financial institutions (FIs), as shown in Graphic 1.

Source: ACAMS and Homeland Security Investigations investigate guide

Visualization by Lauren Kohr and Tiffany Polyak

The proceeds from the low-cost, high-reward ORC crimes have been used to fund further criminal activity, such as:

- Drug and arms trafficking across the southern U.S. border

- Third-party money laundering for the benefit of OTGs in Asia

- Possible terrorist financing through Middle Eastern OTGs and the ORC orchestrators

- Labor trafficking of Central and South Americans forced to act as boosters and steal goods for transnational criminal organizations

- Counterfeit goods and cross-border fraud schemes

In June of 2022, ACAMS, in partnership with Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), published an investigative guide4 for detecting and reporting the illicit financial flows tied to OTG and ORC. Within the guide, several case studies provided by HSI outline the nexus between ORC and other illicit heinous crimes.

The Intersection of ORC and FIs

ORC is believed to cost retailers $68.9 billion or more per year in losses.5 It is undeniable that the corresponding profits from the resale of those products are flowing through the formal, and in some cases informal, banking sectors. As a result, FIs will play a key role in combating ORC and dissolving OTG rings.

OTG Business Hierarchy, Characteristics and Cycle

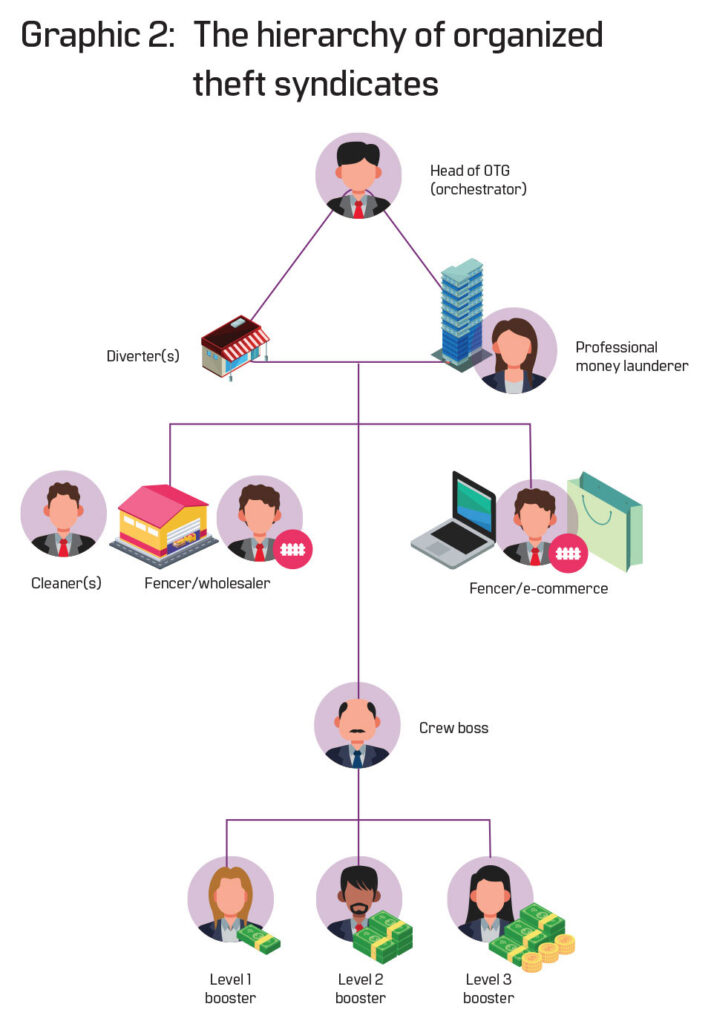

The organized syndicates commonly comprise a hierarchy depending on the level of complexity of the group. Complex organizations begin with boosters—the lowest level of the hierarchy—who are the thieves stealing the product from retailers. The boosters steal items from lists given to them by their crew boss, who communicates with the next level of the hierarchy, the fencers. There are two types of fencers, wholesalers and e-commerce. The e-commerce fencers will “clean” the stolen goods of the tags and trackers, repackage the merchandise and resell the stolen merchandise using online marketplaces. The wholesale fencers will consist of cleaners, who clean and repackage the merchandise, and the fencers who oversee the warehouse and ship to the next level of the hierarchy—the diverters. The diverters are high-level illicit wholesalers or coordinators for secondary sales that own front companies to commingle illicit proceeds and sell stolen merchandise. They also may act as suppliers for retail chains. On the same level in the hierarchy as the diverters are professional money launderers. The professional money launderers own shell companies to move illicit proceeds and hide their origin. At the top of the hierarchy is the ORC orchestrator, or the head of the organization. The ORC orchestrator may head numerous ORC syndicates and may own brick-and-mortar stores that sell stolen merchandise. They may also ship their goods transnationally and be involved in other crimes, like drug trafficking or large counterfeit schemes. The ORC orchestrator may be using the illicit proceeds from ORC to fund their other criminal activities. Graphic 2 outlines the hierarchy of organized theft syndicates.

Source: ACAMS and Homeland Security Investigations investigative guide

Visualization by Lauren Kohr and Tiffany Polyak

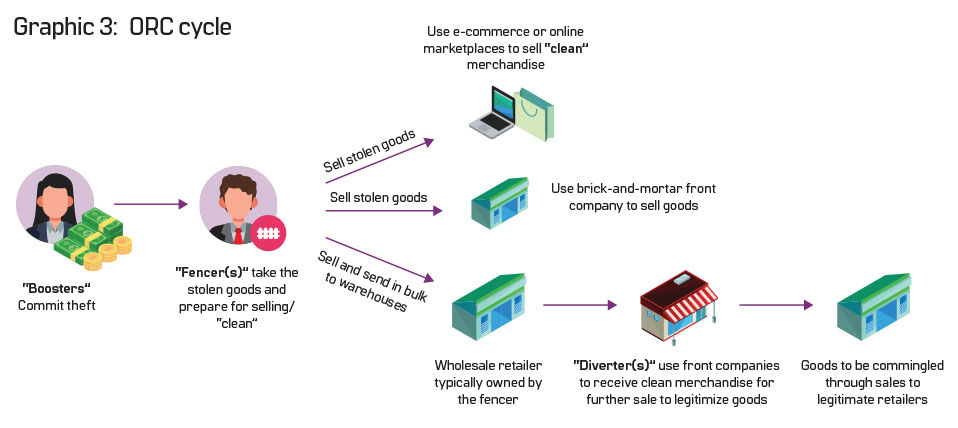

Increasing awareness of the crime cycle will be effective in understanding how to follow the money tied to ORC and assist FIs in spotting illicit activities

The ORC cycle occurs in steps, as shown in Graphic 3, depending on the complexity of the syndicate. Increasing awareness of the crime cycle will be effective in understanding how to follow the money tied to ORC and assist FIs in spotting illicit activities.

Source: ACAMS and Homeland Security Investigations investigative guide

Visualization by Lauren Kohr and Tiffany Polyak

Following the Money: Red Flags and Typologies

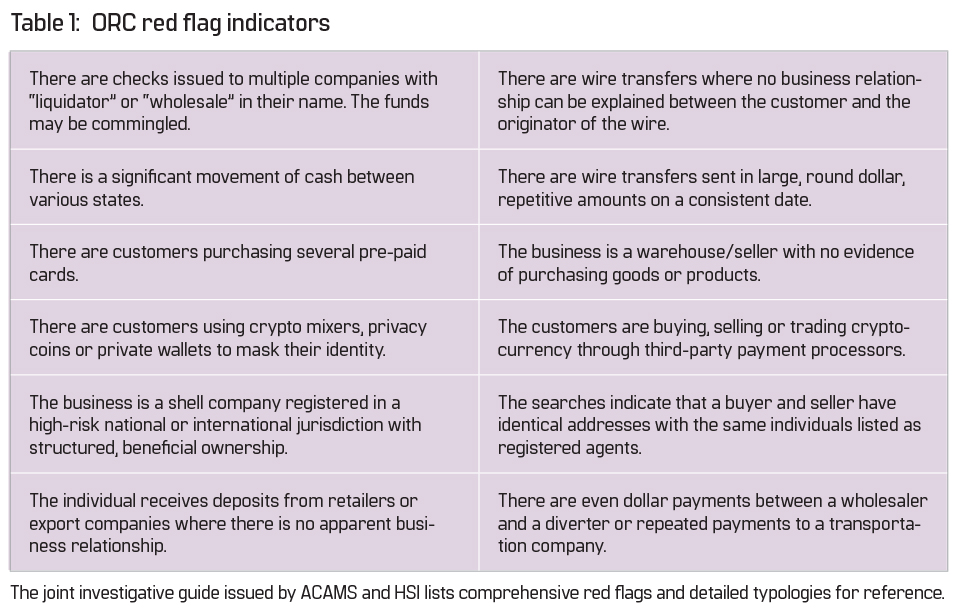

To effectively halt organized criminal activity and dissolve ORC syndicates, it is important for anti-financial crime (AFC) professionals to understand the red flags and typologies related to the illicit financial flows tied to the illicit activity. Some important red flags related to financial activity can be found in Table 1.

ACAMS and HSI partner to fight illicit financial flows tied to ORC.

Pictured left to right: Tiffany Polyak, project coordinator/researcher at ACAMS; Raul Aguilar, deputy assistant director, Transnational Organized Crime, Financial and Fraud Division, Homeland Security Investigations; Steve Francis, acting executive assistant director, Homeland Security Investigations; Lauren Kohr, senior director of AML—Americas at ACAMS.

Press Conference announcing the partnership between ACAMS and HSI to formally launch the Investigative guide on ORC and bring awareness to financial institutions on ways to increase detection and reporting on ORC activities.

Pictured left to right: Ben Dugan, president of the National Coalition of Law Enforcement and Retail (CLEAR); Lauren Kohr, senior director, AML—Americas, ACAMS; Thomas Welch, unit chief, Financial Crimes Unit (FCU), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI); Maria Michel-Manzo, division chief, Transnational Organized Crime, Financial and Fraud Division, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI).

SARs and Other AFC Program Considerations

According to an alert by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), “A financial institution is required to file a suspicious activity report (SAR) if it knows, suspects or has reason to suspect a transaction conducted or attempted by, at or through the FI involves funds derived from illegal activity, or attempts to disguise funds derived from illegal activity; is designed to evade regulations promulgated under the Bank Secrecy Act; lacks a business or apparent lawful purpose; or involves the use of the FI to facilitate criminal activity, including sanctions evasion.”6

Currently, the SAR form does not have a specific SAR field for ORC-related activity. Therefore, if an FI is filing a SAR that is potentially associated with or the circumstances suggest ORC, it is recommended that they use SAR field (38)(Z) (other suspicious activities) and manually write “organized retail crime.” An FI should ensure any other appropriate SAR fields are checked that correspond with suspicious activity identified throughout the investigation.

In addition, LE will proactively use data analysis to identify new cases and complement existing ORC cases by running a series of targeted suspicious activity terms (TSATs) and criteria against SAR filings. LE considers it highly useful information to include TSATs in the SAR narrative as appropriate. If an FI is filing on ORC activity or subjects tied to an OTG, it is recommended, as applicable, that the below TSATs (see Table 2) be used. It would also be useful to describe the relevant behavior and connections between the activities reported and ORC and/or OTG.

Should you file a SAR that you believe is connected to ORC or an OTG, upon filing the SAR notify HSI at: hsi.otg@hsi.dhs.gov.

In addition to the SAR filing, FIs can take other AFC considerations into account to strengthen their investigations relating to ORC. Leveraging the USA PATRIOT Act information sharing through 314(a) and 314(b) is highly useful for both LE and other FIs. Also, if the FI is at an increased risk for ORC proceeds based on their customer risk profile, enhanced training should be considered. The training can consist of ORC awareness, nexus of ORC to Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s Priorities, red flags and typologies, and SAR obligations related to money laundering and other illicit financial crimes, including ORC. Due diligence should also be used as a tool to determine customer risk profiles related to businesses that may be used as front companies for ORC activity.

The Importance of Public-Private Partnerships to Combat ORC and OTG

LE considers it highly useful information to include TSATs in the SAR narrative as appropriate

Public-private partnership and information sharing involving retailers, FIs, LE and other interested industries will serve as the most effective mechanism to combat ORC and dismantle OTGs both domestically and internationally. ACAMS, in partnership with HSI, has taken steps to combat ORC and take down OTGs more effectively. In addition to the investigative guide, ACAMS and HSI will continue to jointly bring awareness to the financial community on steps to reasonably enhance their AFC and SAR filing programs to detect and report illicit proceeds stemming from these crimes.

Conclusion

Criminal organizations need to launder the nearly $70 billion of illicit proceeds gained from ORC activities annually. These organizations are looking to launder their billions through the formal financial sector, unregulated payment processors and online marketplaces. The illicit monies derived from this criminal activity exploit the integrity of our financial system and intersect directly with many of the critical U.S. national priorities that both the public and private sectors are collectively committed to combat. To tackle ORC and take down organized theft groups more effectively, first, FIs must be brought into the awareness and education triangle. Second, public-private partnerships and information sharing channels between retailers, LE and FIs need to be created. Third, as LE and retailers prioritize investigations involving ORC, FIs should look to reasonably enhance their anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing programs to detect and report illicit proceeds stemming from ORC. FIs should ensure proper controls are in place to detect and report illicit activities tied to or involving ORC.

Download the full investigative guide.

Lauren Kohr, senior director, AML—Americas, ACAMS, lkohr@acams.org

Tiffany Polyak, researcher, ACAMS, tpolyak@acams.org

- “Washington Organized Retail Crime Association,” Washington Organized Retail Crime Association, https://www.waorca.org/

- “The Impact of Organized Retail Crime and Product Theft in the United States,” John Dunham and Associates, https://rilastagemedia.blob.core.windows.net/rila-web/rila.web/media/media/campaigns/buy%20safe%20america/ fact%20sheets/the-impact-of-organized-crime-and-theft-in-the-united-states.pdf

- Hedgie Bartol, “The growing issue of organized retail crime,” Axis, April 26, 2021, https://www.axis.com/blog/secure-insights/organized-retail-crime/

- “Organized Theft Groups and Organized Retail Crime,” ACAMS and Homeland Security Investigations, https://www.acams.org/en/organized-retail-crime#summary-14c8bdad

- “Cornerstone: Collaborating with the Financial Industry to Prevent Crime,” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, January 2021, www.ice.gov/cornerstone

- “FinCEN Advises Increased Vigilance for Potential Russian Sanctions Evasion Attempts,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, March 7, 2022, https://www.law360.co.uk/articles/1471451/attachments/0; See 31 CFR § 1020.320, 1021.320, 1022.320, 1023.320, 1024.320, 1025.320, 1026.320, 1029.320 and 1030.320.