International trade and trade finance play prominent roles in the economic development of countries. While conventional trade acts as an engine for economic growth and development, sustainable international trade can tackle environmental challenges and prevent the exploitation of natural resources and their criminal use under the garb of international trade. As stated by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), “International trade offers unique opportunities to build a prosperous, climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable world.”1

Based on a 2020 ICC trade finance report, the current worth of the trade finance market is $5 trillion annually.2 However, this can be eclipsed by the growing trend of environmental crime which, per the United Nations (U.N.), is estimated at between 5% and 7% annually,3 which is two to three times the growth rate of the global economy. According to the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development, Illicit trade drains nearly 3% of the world’s economy.4

Environmental crime is one of the most profitable criminal enterprises, generating $110 billion to $281 billion in criminal gains each year. It covers a wide range of unlawful activities, such as illegal logging, illegal wildlife trade and waste trafficking.5 This type of crime ranks as the third-largest illicit activity in the world, following the trafficking of drugs and counterfeit goods.

Banks play a crucial role in financing trade. As the financing arm of international trade, banks should be aware of the impact of environmental crimes on trade so they can take the necessary steps to identify and prevent themselves from financing trade involving green crimes. Sustainable trade finance goes a long way to help achieve the U.N.’s 20306 Agenda for Sustainable Development to ensure prosperity for people and the planet. While trade finance helps prosperity for people, sustainable trade finance ensures prosperity for people and the planet. Thus, aligning trade financing to environmental, social and governance (ESG) goals laid down by the U.N. will help achieve the ESG goals within the deadline set for 2030. With the Basel Committee’s recommendation of integrating sustainability principles in the areas of credit risk measurement and management, many banks are already integrating sustainability risks into credit risk management procedures for clients and conducting sustainability-related due diligence.

Scope

The concept of protecting people and the planet is gaining much-needed importance in today’s world. Illegal logging impacts the environment and depletes nature of its much-needed resources. Banks have an important role in mitigating these crimes since the funds flow through the banking sector.

A two-pronged approach can be used by banks to assess and mitigate the risk.

- Identify and assess the vulnerability from a financing perspective and take necessary steps to ensure that no financing is done to customers/beneficiaries involved in such crimes, specifically while financing trade. A bank can conduct a risk assessment based on customer, sector, jurisdiction, etc., to understand the type of customers involved in sectors that can be a threat to sustainability. Based on this risk assessment, vulnerable customers can be identified and assessed. The risk assessment can show two aspects:

- Customers who are not aware that they are a threat to sustainability but are a threat owing to the sector in which they operate (for example, gold and precious metal dealers, art dealers, etc.)

- Customers who are aware and are witting associates/accomplices

In both scenarios, banks should take necessary steps to ensure sustainable trade finance and customers who fall in category b should be reported as well.

- Identify and assess the vulnerability from a financial crime perspective and ensure transactions are subject to enhanced due diligence (EDD) and monitoring so that all suspicions are identified and reported.

This article discusses the vulnerability as well as the due diligence banks should undertake to ensure both sustainable trade finance as well as prevent and mitigate green crimes.

Green Crimes and Trade Finance—Vulnerability

Environmental crimes encompass illegal activity that harms human health, nature and natural resources by damaging environmental quality, including increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, driving biodiversity loss and causing the overexploitation of natural resources. Environmental crimes like illegal mining impact human health and encourage human trafficking and child slavery.

This category of crimes includes:

- Wildlife trafficking

- Illegal logging

- Illegal fishing

- Illegal mining

- Waste and hazardous substances trafficking

In conflict zones, environmental crimes, including illegal exploitation and oil theft, provide an estimated 38% of illicit income to armed groups, more than any other illicit activity, including drug trafficking.7

Environmental/green crimes are a cause of concern for banks while financing trade. Specific vulnerable sectors include natural resources such as gold and precious metals, minerals and related products, and forest products like timber, which can lead to both human and environmental exploitation.

In 2021, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued a notice to call attention to an upward trend in environmental crimes and associated illicit financial activity. In this notice, FinCEN has required all financial institutions to file a suspicious activity report on these crimes.

Banks financing trade of highly vulnerable sectors should be aware of the related risk of green crimes since green crimes not only deplete the planet of resources but also divert funds into the hands of terrorists and criminals. For example, when banks finance trade of high-risk sectors like natural resources, they need to be aware that the resources can be extracted from mines in conflict zones, which contravene environmental regulatory thresholds, thus impacting the health and ecosystems of surrounding areas. Illegal mining generates an estimated $12 billion to $48 billion a year in criminal proceeds, with illegally mined gold and diamonds considered to be the most significant source materials.8

Banks are currently aware of the money laundering and terrorist financing risk of the gold and precious metal sector; however, this article emphasizes the need for banks to be aware of the aspect of green crimes as well. Also, the complex supply chain between the origin and end destination of precious metals like gold can accentuate the risk.

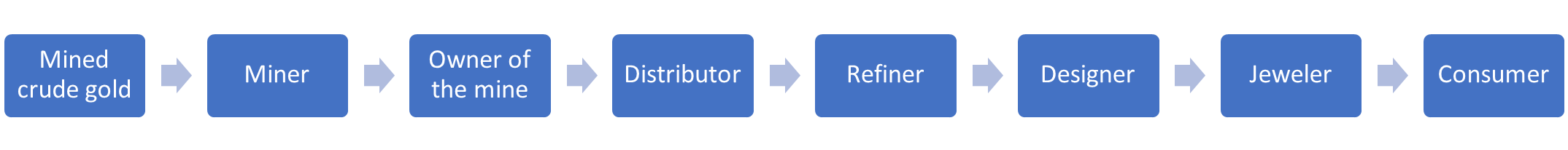

Graphic 1: The Gold Sector as an Example

It is the jeweler who is often financed by banks (either through a letter of credit or open account transfer), and since the certificate of origin is often issued at the country of design or refining, the origin/source of gold is lost to the banks.

The risk/vulnerabilities may arise from the following factors (as shown in Graphic 1):

- The mine may be illegal and not have the proper government authorizations; the mine may be a threat to the environment; and/or the mine may be in a high-risk or sanctioned jurisdiction.

- The miner may be an enslaved human or a child who is forced into mining (human/child trafficking).

- The mine owner may be an organized crime group or corrupt politicians.

- The distributor may be dealing in gold/precious metals smuggled in from high-risk countries and/or sanctioned countries.

- The refiner, designer and/or jeweler may be a witting or unwitting accomplice.

Banks need to be aware of these risks and ensure that the original gold is sourced from responsible gold mines. The World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles address key ESG issues to which the gold mining sector can adhere.9

Another threat to the environment that can be inadvertently financed by banks is illegal wildlife trafficking. The spread of zoonotic diseases (COVID-19, for example) emphasizes the importance of wildlife trading sustainably. The U.N. estimates that 7,000 different species are illegally trafficked.10 Criminals can misuse the legitimate wildlife trade and other import-export type businesses as a front to move and hide illegal proceeds from wildlife crimes.11 These trades—such as the importing of artifacts, such as those made from the ivory of African elephants, and traditional medicines, such as rhino horn powders—can be inadvertently funded by banks, for example.

Another sector where banks need to be aware deals with scraps and secondhand goods. Waste and hazardous substance trafficking can be done under the guise of scrap trading and the sale of secondhand goods. Containers filled with hazardous or noncompliant waste can be misclassified as recycled materials and exported to developing or middle-income countries.

Illegal logging involves illicit trade in timber in violation of national and international laws. This is often commingled with the legal timber trade and involves shell companies in multiple jurisdictions. Banks need to be aware of the country of origin of timber and the legality of the transaction.

In order to ensure sustainable trade finance and prevent green crimes, banks can adopt a two-pronged approach:

- Due diligence to ensure sustainable trade financing

- Due diligence to prevent green crimes

Due Diligence to Ensure Sustainable Trade Financing

- Banks need to develop a green financing policy in line with the International Finance Corporation’s performance standards12, the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals13 and the ICC’s definition of sustainability standards in financing solutions.14

- Banks should create an exclusion and/or sensitive sector list. Before approving a financing application, banks need to check the origin of the raw materials and the entire supply chain. They need to ensure that the business does not fall into the exclusion or the sensitive sector list. Necessary flags should be raised to the compliance team to ensure that the transaction is not vulnerable to green crimes and if it is, the necessary EDD is done and monitored.

- They should undertake environmental and social due diligence (ESDD) before onboarding a customer.

- At the time of onboarding/creating the customer risk profile, the customer needs to be informed about the bank’s environment and sustainability policy. The customer should acknowledge the environmental and social policy of the bank.

- Adopting a risk-based approach, they should request international documentation, such as the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 14001 (environment), OHSAS (Occupational Health and Safety Assessment Series) 18001 or ISO 45001 (occupation health and safety) certificates to check and verify the customer’s commitment to ESG standards expected by the bank. This documentation should be used to verify the ESG compliance of the supplier/beneficiary as well.

- An underlying trade transaction, both domestic and international, passes through three stages:

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

- Distribution

Assessing a transaction across each of these stages provides transparency on whether the trade transaction is sustainable.

- Shipment methods/transportation used should be aligned with the economic, social, human and environmental aims. Certificates can be requested to ensure that the vessel and transportation used comply with the green principles laid down by the U.N., for example, requesting that the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) certificate satisfies that the transportation follows sustainability principles.

- Once financing is provided, banks need to constantly monitor the transactions and trigger an alert if there are any breaches or noncompliance.

Due Diligence to Prevent Green Crimes

The first step in this process would be to do a specific green crime risk assessment, identifying the vulnerability to green crimes. The risk assessment would involve the following.

Identification

The vulnerabilities need to be identified based on the following:

- Customers who are vulnerable to green crimes or who have customers/suppliers who can be vulnerable to green crimes (i.e., scrap dealers, antique dealers, jewelers, precious metal dealers, etc.)

- Products/services which can be vulnerable to green crimes (i.e., letters of credit)

- Jurisdictions vulnerable to green crimes (jurisdictions with rich natural resources listed as high-risk/conflict zones by the FATF/ Transparency International)

- Sector risk (i.e., gold and precious metals, oil and gas, natural resources like timber, etc.)

Once the vulnerabilities are identified, the next step would be to understand the probability that these identified vulnerabilities would be converted into a threat. The customer risk profile of each vulnerable customer needs to be created, scored and monitored based on usual transactions and any unusual transaction needs to be triggered for additional due diligence (as depicted in Table 1).

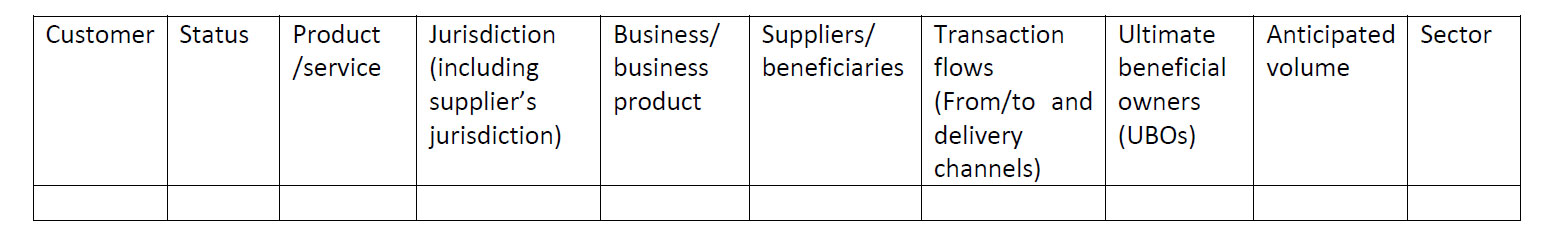

Table 1: Example of a Customer Risk Profile to Identify Green Crime Risk

Based on the customer risk profile as created above and the resultant risk scoring, the following steps should be taken:

- Do an EDD on each identified supplier/beneficiary, including identifying, verifying and screening the UBOs.

- Create transaction patterns and history for each customer and ensure any deviation is identified and triggered (via software to establish transaction patterns and trigger deviations).

- Assess patterns of optimal shipping routes (for example, use of route optimization logistic software or similar) so that circuitous routes and use of unnecessary transshipment zones can be identified.

- Undertake a detailed transaction due diligence.

- Require a certificate of origin of the raw materials and the finished goods (risk-based).

- Conduct due diligence on each party involved in the supply chain (risk-based). Supply chain due diligence should involve the following:

- Source countries

- Transit countries

- Destination countries

- End-use certificates or utilization certificates from an independent, third-party consultant should be obtained post-financing.

- Fund flows need to be subject to enhanced monitoring by banks, specifically when the customer, product, jurisdiction or transaction is vulnerable to environmental crimes.

- Obtain relevant certifications to ensure the origins of the raw materials are not from conflict zones (e.g., gold and precious metals), the animals and animal products imported are not protected species or the timber is not from protected forests.

- Some examples of certifications include the following:

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) permits/certifications

- Adherence by customers/suppliers/refineries to the World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles15

- Conflict-free gold reports from customers/suppliers/refineries

- Kimberly Process Certification for diamonds

Conclusion

The pandemic, which has shaken the world, has succeeded in highlighting the importance of protecting the planet. We have realized that safeguarding the planet is key to protecting the Earth’s people, and ultimately, that healthy people and a healthy planet contribute to a healthy economy. The black swan event has proved that there is a direct correlation between the planet, people and profits.

It is extremely important for banks to transition from traditional trade finance to sustainable trade finance. While profits were a primary consideration in trade finance products, the international impetus on ESG principles have pushed banks to consider the planet and population in addition to profits.

Banks need to relook at the existing policies and procedures pertaining to trade finance and build in ESG considerations. The three lines of defense should be actively involved in ensuring sustainable trade finance and the prevention of green crimes.

The first line of defense should actively implement the ESG compliance policies and procedures at the time of onboarding the client as well as before considering and granting any facility. Simultaneously, at a minimum, they should identify and assess the customer, product, transaction, jurisdiction and sector risk for vulnerability towards green crimes.

The second line of defense should monitor both on an ongoing basis and ensure any unusual transactions are triggered and flagged.

The third line of defense should review periodically and ensure necessary reporting.

Going green—in terms of ensuring green financing as well as preventing green crimes—goes a long way in protecting the “three Ps”: Planet, people and profits.

Zeeba Askar, head of banking and finance and the Sustainability Academy, Bahrain Institute of Banking and Finance (BIBF), Kingdom of Bahrain, zaskar@bibf.com

Savitha Raghavan, senior lecturer, BIBF, Kingdom of Bahrain, savitha@bibf.com

Dr. Chithra Suresh, senior lecturer, BIBF, Kingdom of Bahrain, chithra@bibf.com

- “ICC Standards for Sustainable Trade and Sustainable Trade Finance,” ICC, https://iccwbo.org/publication/icc-standards-for-sustainable-trade-and-sustainable-trade-finance/

- “ICC opens consultation on draft global standards for Sustainable Trade and Trade Finance,” ICC, October, 11, 2021, https://iccwbo.org/media-wall/news-speeches/icc-opens-consultation-on-draft-global-standards-for-sustainable-trade-and-trade-finance/

- “The rise of environmental crime: A growing threat to natural resources peace, development and security,” United Nations Environment Programme, 2016, https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/7662

- “Global actors gather to forge a common front against illicit trade,” United Nations Conference

On Trade and Development, January 20, 2020, https://unctad.org/news/global-actors-gather-forge-common-front-against-illicit-trade# - “Money Laundering from Environmental Crime,” Financial Actions Task Force, July 2021, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Money-Laundering-from-Environmental-Crime.pdf

- “The 17 Goals,” United Nations, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- “FinCEN Calls Attention to Environmental Crimes and Related Financial Activity,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, November 18, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/FinCEN%20Environmental%20Crimes%20Notice%20508%20FINAL.pdf

- “Money Laundering from Environmental Crime,” Financial Action Task Force, July 2021, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Money-Laundering-from-Environmental-Crime.pdf

- “Responsible Gold Mining Principles,” World Gold Council, 2019, https://www.gold.org/esg/responsible-gold-mining#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20we%20launched%20the,what%20constitutes%20responsible%20gold%20mining

- “FinCEN Calls Attention to Environmental Crimes and Related Financial Activity,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, November 18, 2021, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/FinCEN%20Environmental%20Crimes%20Notice%20508%20FINAL.pdf

- “Money Laundering and Illegal Wildlife Trade,” Financial Action Task Force, June 2020, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/money-laundering-wildlife-trade.html

- “Banking on Sustainability: Financing Environmental and Social Opportunities in Emerging Markets,” IFC, January 1, 2007, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/434571468339551160/banking-on-sustainability-financing-environmental-and-social-opportunities-in-emerging-markets

- “The 17 Goals,” United Nations, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- “ICC Standards for Sustainable Trade and Sustainable Trade Finance,” ICC, https://iccwbo.org/publication/icc-standards-for-sustainable-trade-and-sustainable-trade-finance/

- “Responsible Gold Mining Principles,” World Gold Council, https://www.gold.org/industry-standards/responsible-gold-mining