"There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen,” wrote Lenin in 1917.1 His statement was a prescient warning of the perils that lay before the world, namely World War I and two historic revolutions in Russia. The events of 1917 ushered in a then-novel legal posture dictating that international trade with foreign adversaries would no longer be permitted. The use of both, trade controls and financial sanctions, were concepts that these events brought about to disrupt the general economic and commercial functions of enemy nations.

The U.S. government and Allied nations came to believe that export controls on a wider array of commodities, coupled with the customary controls on military items and supporting activities, was a preferential route toward meeting national security and foreign policy objectives. Trade controls, especially those governing exports, are almost always event-driven and inherently political. For Russia and the U. S., there has been a long-standing philosophical difference concerning their importance and enforcement. Reviewing world events involving these two nations over the past several decades provides a relevant and—unfortunately, due to the invasion of Ukraine—timely opportunity to better understand the current export control environment.

The History of Export Controls

The present-day history of export controls began in 1917 when the U.S. adopted the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) and Executive Order 2729-A. The TWEA empowered the president, during a time of war, to severely limit economic activities such as imports, exports, financial transactions, contractual fulfillment and investments with designated enemy countries and with nationals of these countries. The law set the basis for financial and trade sanctions and established an export licensing mechanism for the U.S. The law also gave the U.S. government jurisdiction to apply the law extraterritorially to their enemies, their enemy’s friends and to “withhold or refuse licenses to trade either directly or indirectly with, to, or from, or for or on account of, or on behalf of, or for the benefit of, any other person, with knowledge or reasonable cause to believe that such other person is an enemy or ally of enemy, or is conducting or taking part in such trade directly or indirectly for or on account of, or on behalf of, or for the benefit of, an enemy or ally of enemy.”2

Executive Order 2729-A created the Office of Alien Property Custodian (APC) which permitted the U.S. government to seize “any money or other properties owing to or belonging to or held for, by or on account of, or on behalf of, or for the benefit of any enemy or ally of an enemy.”3 The U.S. was not alone in its multipronged approach to disrupting the livelihoods and holdings of enemies. The U.K. passed the Titles Deprivation Act of 1917, which stripped enemies “of British dignities” and royal titles and of the ability to vote. The U.K. defined “enemy” as those individuals who voluntarily resided in an enemy country, served in the enemy forces, or “in any way rendered assistance to the enemy.”4 While the U.S. was not alone in advancing the use of sanctions and trade controls as instruments of foreign policy, they were unique in the depth, breadth and seriousness with which they implemented and enforced the new rules.

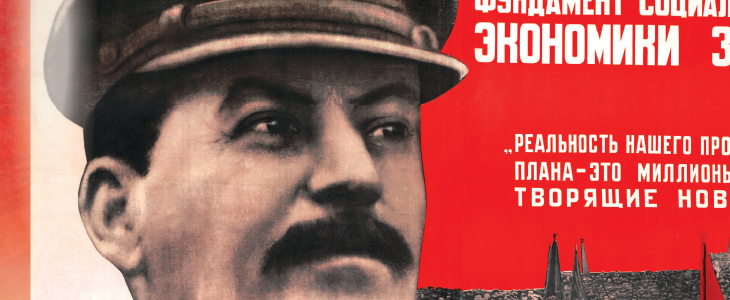

Russia—1917

In 1917, while other powerful nations were focused outward, Russia was in the throes of radical political transformation at home. Reeling from WWI’s deep losses, with nearly 5 million wounded, 3.3 million civilian and military casualties and fearing a mutiny from the rank and file, the Imperial Russian Army convinced Tsar Nicholas II to step down.5 He abdicated the throne to make way for a socialist form of government in Russia. Unfortunately, the new government primarily sought to advance the interests of Russian capitalists, nobility and the aristocracy. Despite war-induced famine and widespread disdain for continued involvement in the war, Russia’s newly formed government inexplicably continued conscription and deployment of Russian males. Russian citizens fed up with government corruption, inefficiency, as well as loss of life and livelihood had been through enough. The second Russian Revolution saw farmers, peasants and the military topple the new government, transferring all its authority to Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks.6

The Soviets and Ukraine—1917

The Russian Empire effectively ended in 1917. Thereafter began Soviet rule, which would continue for the next six decades. Despite the ongoing civil war, one of the new Soviet government’s first actions was to confiscate the assets of their enemies and reestablish their power in the newly formed independent republics that had previously seceded from the Russian Empire. The Soviets focused on “repatriating” Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia and Ukraine. The first Bolshevik Ukrainian republic was founded in December 1917 as the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. WWI destroyed Russia’s economy, but the Soviets’ politics and actions destroyed their prestige as a European power.7

Soviet Self-inflicted Crisis

Mass purges, exiles and executions of political enemies raged for three years, including an estimated 30,000 of the most senior and experienced Soviet military commanders and soldiers

The Soviet Union continued in a state of mostly internal, self-inflicted crisis with nearly constant civil wars. In 1924, Joseph Stalin assumed leadership following Lenin’s death. Beginning in 1936, a paranoid Stalin began his campaign of “Great Terror.” Mass purges, exiles and executions of political enemies raged for three years, including an estimated 30,000 of the most senior and experienced Soviet military commanders and soldiers. According to author and historian Peter Whitewood, “Stalin was decapitating his military at the very moment that Europe was bracing itself for total war.”8

As the world became increasingly aware of Stalin’s unmitigated death and destruction of his people, his isolation on the world stage increased. Stalin’s purge of his military in 1937 caused Britain and France to rethink an alliance with someone they considered “mad.”9 This meant that the Soviets faced the prospect of a fight with Nazi Germany alone, a battle they undoubtedly knew they could not win. In 1939, Stalin and Hitler signed a mutual nonaggression pact, promptly invaded Poland among other nations, and divvied up the land and plunder among themselves as they saw fit.10

Export Controls Go Global

In the U.K., January 1, 1939, saw the first set of sanctions and trade controls enacted when the Import, Export and Customs Powers Defense Act came into force

A furious Britain and France declared the U.S.S.R. an enemy nation. Meanwhile, the weapons industries of Europe had been doing a brisk business from the end of WWI to the start of WWII, supplying anyone who had money to pay for them with weapons and other machines of war. The governments of France and Britain finally began to think better of this commercial practice, as they now faced an enemy using weapons against them that they had supplied.11 The importance of export controls had finally hit home. In the U.K., January 1, 1939, saw the first set of sanctions and trade controls enacted when the Import, Export and Customs Powers Defense Act came into force. This emergency legislation made it a criminal offense to export military and dual-use goods to enemy countries.12 On April 18, 1939, France adopted the Decree-Law, which prohibited exports of military equipment, arms and munitions without a license.13

Following the end of WWII, the U.S. and a handful of European nations enacted a peacetime export control policy. The U.S. Export Control Act of 1949 was the first such regulation that sought to use trade controls as a pragmatic constraint on imperialistic ambitions before those ambitions had time to turn to action.14 The Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM) was established in 1949 among the U.S., most NATO allies, Australia and Japan. COCOM’s purpose was to control exports to the Warsaw Treaty countries (Soviet Union, Albania, Poland, Romania, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria) and China. From the start, however, the items on which COCOM could agree were limited.15 Consequently, the U.S. imposed controls on many items unilaterally and with a tougher stance on enforcement.

U.S.-Soviet Detente

In the late 1960s, the growing importance of international trade to the U.S. economy along with the U.S.-Soviet detente created a cautious willingness to relax some export controls on trading with the Soviets. The U.S. Congress worked to strike a balance between national security and expanded economic engagement with the Soviet Union. The newly created Export Administration Act (EAA) of 1969 breathed life and complexity into export controls by removing the near-total embargo on trading with the enemy and instead considered only what was worth controlling for export.16

Soviets Invade Afghanistan

From the standpoint of export controls, detente ended in 1979 when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. Indisputable evidence emerged that the Soviets had used the relaxed U.S. trade controls to legally and illegally obtain Western dual-use technology to modernize its military. As a result, President Carter, acting under provisions of the EAA, denied all U.S. technology exports to the Soviet Union.17

And because not every country that should have made a similar decision to control arms and other types of dual-use products to the Soviet Union would make such a decision, the U.S. further expanded the extraterritorial application of their export controls and financial sanctions and instituted congressionally mandated reexport controls that applied to any product, technology or service anywhere using American parts, components or know-how. The current U.S. Foreign Direct Product Rule stems from this era, as do stringent reexport controls and in-country transfer licensing requirements.18

End of the U.S.S.R.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 directly impacted the export control landscape. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, most countries modified their export control policies toward the former U.S.S.R. Russia also built an export control system following mostly U.S. directives. On April 11, 1992, Presidential Decree No. 388, “On Measures for Creating an Export Control System in Russia,” created the first system of nonproliferation export controls in Russia.19 In August 1992, Russia issued its first-ever military export license and many more followed.

In the opinion of Western nations, far too many approved exports of arms to the world’s highest bidders were leaving Russia. By the mid-1990s, the lack of competently implemented and enforced export control concerns involving Russia began to surface in official dialogue among the U.S. and other developed countries.20 A constellation of factors highlighted a discrepancy between Russian legislative and regulatory policy and their actual implementation and enforcement.

According to Dr. Vladimir Orlov, editor-in-chief of the Moscow-based PIR Center, the root of this discrepancy was a philosophical difference. He observed that “in the transition from a command-and-control system to a market economy, the market has been understood by many [Russians] as allowing the freedom to make money regardless of laws and, in particular, to export without any limits.”21 This difference created an inevitable gap between export control policy and practice in Russia from the outset.

Export Controls Need Enforcement

The U.S., U.K. and France worked closely with various Russian officials to expand their implementation and enforcement of export controls, wanting to stop the seemingly unfettered spread of military and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) commodities around the world. Yet, in April 1999, the U.S., wanting to send a message, imposed sanctions on three Russian defense companies for weapon delivery system exports to Syria. Igor Sergeyev, then-defense minister of Russia, called the sanctions “groundless.”

The Russians believed the sanctions were economically motivated rather than driven by the far more rational explanation of WMD nonproliferation security concerns. Many in the Russian government believed that the U.S. and other Western powers were attempting to limit Russia as a competitor in the defense sector—“kill a business rival with a political weapon.”22 It was increasingly believed that the Russians said one thing and did another. The Americans cared far more than the Europeans about Russia’s flagrant flaunting of export control enforcement, and thus an export control stalemate held for the next nearly 20 years.

February 2022

The depth and reach of the newly enacted export controls are not all that dissimilar to the nearly complete embargo on goods to the former Soviet Union

No single world event has galvanized a harmonized approach to controlling trade with an enemy and its supporters quite like the unprovoked invasion of Ukraine. Europe, the U.S., and many other nations have taken the steps necessary to coordinate and harmonize the implementation and enforcement of “significant, novel and complex controls on the export and reexport to, and transfer within, Russia and Belarus of a wide range of previously uncontrolled U.S.- and foreign-made items.”23 The depth and reach of the newly enacted export controls are not all that dissimilar to the nearly complete embargo on goods to the former Soviet Union. In sum, we are back to 1917, and there is little that can be exported or reexported that involves Russia or their friend Belarus.

Anne Marie Lacourse, consultant, Dow Jones Risk & Compliance, USA, annemarie@lacourse.us

- N. Lenin, Leon Trotzky et al., “The Proletarian Revolution in Russia,” The Communist Press Publishers, 1918, https://books.google.com/books?id=3_MeAAAAMAAJ&q

- B. Coates, “The Secret Life of Statutes: A Century of the Trading with the Enemy Act,” Modern American History, 1(2), 151-172, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1017/mah.2018.12

- Woodrow Wilson, “Executive Order 2729A—Vesting Power and Authority in Designated Officers and Making Rules and Regulations Under Trading with the Enemy Act and Title VII of the Act Approved June 15, 1917,” The American Presidency Project, October 12, 1917, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/275575

- Titles Deprivation Act 1917, Legislation.gov.uk, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo5/7-8/47

- World War I Casualties, Repères, http://www.centre-robert-schuman.org/userfiles/files/REPERES%20%E2%80%93%20module%201-1-1%20-%20explanatory%20notes%20%E2%80%93%20World%20War%20I%20casualties%20%E2%80%93%20EN.pdf

- Fedor Aleksandrovich Gaida, “Governments, Parliaments and Parties (Russian Empire),” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Updated October 8, 2014, doi: 10.15463/ie1418.10189

- Robert V. Daniels. A Documentary History of Communism in Russia: From Lenin to Gorbachev. University Press of New England, 1993

- Peter Whitewood. The Red Army and the Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Soviet Military. University Press of Kansas, 2015, ISBN: 0700621172

- Robert Gellately, Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe. Knopf, 2007, ISBN 978-1-4000-4005

- “German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/German-Soviet-Nonaggression-Pact

- Jonathan A. Grant, Rulers, Guns and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Harvard University Press, 2007

- “Import, Export and Customs Powers (Defence) Act 1939,” Legislation.gov.uk, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/2-3/69/contents

- O. Kirchheimer, “Decree Powers and Constitutional Law in France under the Third Republic,” The American Political Science Review, 34(6), 1104–1123, 1940

- Tamotsu Aoi, “Historical Background of Export Control Development in Selected Countries and Regions,” Center for Information on Security Trade Controls, Tokyo, Japan, 2016, https://www.cistec.or.jp/english/service/report.html

- Vladimir A. Orlov, “Export Controls in Russia: Policies and Practices,” The Nonproliferation Review, Fall 1999, https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/orlov64.pdf

- B. Coates, “The Secret Life of Statutes: A Century of the Trading with the Enemy Act.” Modern American History, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1017/mah.2018.12

- Tamotsu Aoi, “Historical Background of Export Control Development in Selected Countries and Regions,” Center for Information on Security Trade Controls, Tokyo, Japan, 2016. https://www.cistec.or.jp/english/service/report.html

- “The U.S. Export Control System and the Export Control Reform Initiative,” Congressional Research Service, Updated June 7, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46814

- Baidya Bikash Basu, “Russian Military-Technical Cooperation: Structures and Processes,” Strategic Analysis, June 2001, https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/sa/sa_june01bab01.html#txt6

- “Statement of the Press Service of the Russian Security Council,” NTI.org, June 23, 1999, https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/april-1999-russian-federation-security-council-meeting-nuclear-weapons/

- Vladimir A. Orlov, “Export Controls in Russia: Policies and Practices,” The Nonproliferation Review, Monterey Institute of International Studies, Fall 1999, https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/orlov64.pdf

- Victor Mikhailov, “Uchet I Kontrol Yadernykh Materialov: Vzglyad Glavy Minatoma (Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials: Views of Minatom’s Head),” Yaderny Kontrol, No. 2, pp. 10-11, February 1995

- International Trade Alert: “U.S. Government Imposes Expansive, Novel and Plurilateral Export Controls Against Russia and Belarus,” Akin Gump.com, March 8, 2022, https://www.akingump.com/a/web/ayCoxfB41bXG1H8Y4jUWup/3FFMet/us-government-imposes-expansive-novel-and-plurilateral-export.pdf