Twelve years after the Financial Action Task Force’s first advisory report,1 trade-based money laundering (TBML) remains the most sophisticated method to launder illicit funds and move “value” within/across country borders, in the guise of legitimate trade transactions. Hundreds of billions of dollars are laundered via TBML annually2 and it is fair to say that TBML has become a global menace. This article briefly explores the Indian experience in combating TBML and comes in the wake of India’s largest-ever bank fraud, estimated at $2.1 billion. It identifies common features noted across Indian TBML schemes, outlines some of the action taken by the Indian government, the Financial Intelligence Unit - India (FIU-IND), the regulator Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Indian customs and law enforcement agencies (LEAs), and suggests an approach to combat its malice.

The TBML Quandary

Across a group of bankers, try checking how many actually know about a letter of credit (L/C), bill of entry (BoE) or buyer’s credit. Chances are, few will! Welcome to the world of trade finance—a highly complex and specialized area with its own jargons and practices, not to mention the many counterparties, intermediaries, banks and the myriad of goods, commodities and services involved in the millions of trade transactions processed by banks daily. Due to increasing regulatory expectations and trade complexity, bankers find themselves in a quandary. So, what can be done?

In the author’s view, combating TBML requires a paradigm shift, an integrated approach and the application of risk-based, intelligence-led and targeted measures.

The Shifting Paradigm

FIU-IND issued TBML red flag indicators (RFIs) and guidance in late 2015. Beforehand, banks relied on their anti-money laundering (AML) transaction monitoring and screening systems to screen customers/counterparties in trade transactions for possible matches against sanctions/negative lists and relied primarily on their second lines of defense (anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing [AML/CTF] transaction monitoring teams). These in turn were heavily dependent upon banks’ AML system-generated transaction alerts to undertake customer investigations/due diligence and to determine suspicious transactions. This traditional approach is insufficient in combating TBML for the following two reasons:

- First, in the context of transaction monitoring, TBML RFIs are varied and require banks to be vigilant on various aspects of trade transactions namely customer profiles, account transactions, trade documents, consignment, payment mechanisms, counterparties, trade practices, shipping routes, dual-use goods, valuations, etc. All these aspects cannot be readily configured into an automated AML system. This would require banks to also rely on the trade knowledge/skills of their first lines of defense (branch trade desk and trade processing unit staff) to spot the red flags and identify anomalies in trade transactions at the point of customer contact/transaction processing.

- Second, in the last three years, two of India’s largest TBML schemes have emanated from only one branch of its two leading public sector banks. Each scheme exploited a weakness. The $0.88 billion foreign exchange remittance scam (2015) exploited, among other things, the branch’s follow-up procedures for obtaining evidence of imports of goods (BoEs issued by Indian customs) for advance import remittances structured below $100,000 (RBI reporting limit).3 Whereas the $2.1 billion fraud in 2018 was facilitated because the branch’s core banking system was not integrated with the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) system, among other reasons.4

Combating TBML requires a paradigm shift, an integrated approach and the application of risk-based, intelligence-led and targeted measures

Integrated Approach

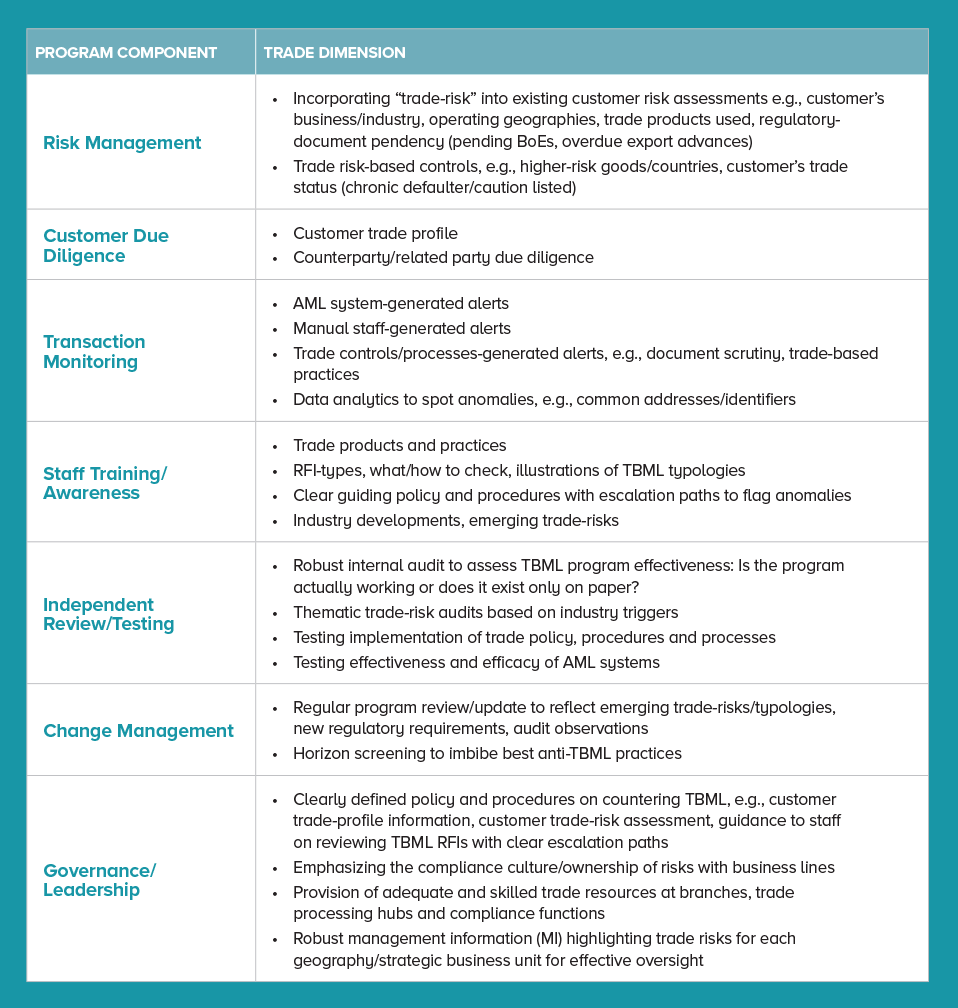

Although banks already have their traditional AML/CTF programs in place, to effectively combat TBML, it is important to add the “trade dimension” to each aspect of their programs (see table below).

A common pitfall is to implement the TBML RFIs as a separate framework/process, rather than into the main AML/CTF program.

Another aspect of an integrated approach is highlighted by the $2.1 billion bank fraud, which was classified by RBI as an operational risk arising on account of delinquent employee behavior and failure of the bank’s internal controls.5 This case provides a classic example of how operational risk may manifest into a money laundering scheme and builds a strong case for an integrated financial crime risk management program which entails the following:

- Reviewing the bank’s internal systems, controls and procedures (especially as they relate to the creation of “value” or contingent liability), allocation of staff duties/responsibilities, and managing conflicts of interest to identify and plug operational risks.6

- Adopting an integrated approach to financial crime risk management by ensuring effective coordination of all financial crime compliance functions within the bank such as AML, counter-terrorist financing, sanctions compliance, anti-fraud, anti-bribery and corruption, countering tax evasion and cyber-risk management.

Deploying Risk-Based, Intelligence-Led and Targeted Measures

The following are common features noted across Indian TBML schemes along with suggested pragmatic measures:

Related Counterparties or Shell Companies Owned/Controlled by TBML Perpetrators

Trade products are structured to cater to differing interests of genuine transacting parties. These act as a “check” on each other; for example, the seller’s interest is to receive the contracted price whereas the buyer is interested in receiving the contracted goods (right type, quality, quantity and price). It follows that if any party alters or does not deliver on its terms, the aggrieved party acts as a “check.” Therefore, in case of non-delivery or over-invoicing/valuation of goods supplied under an L/C, the buyer should alert its bank. When counterparties act in collusion, this “check” is removed and TBML risk increases. Therefore, this constitutes an important checkpoint.

While the Indian government is presently working on an official definition of a “shell company” to aid its investigative processes, LEAs have outlined the following broad features:

- Set up with a nominal paid-up capital

- Typical high share premium

- Investing in unlisted companies

- No dividend income

- High cash-in-hand

- Private companies as majority shareholders

- Low turnover/operating income

- Nominal expenses

- Nominal statutory payments

- Minimum stock-in-trade and fixed assets

Many shell companies are known to operate from the same address and/or have nominee directors often unaware of company transactions/operations.7

As part of the Indian government’s strategy to counter black money,8 the Ministry of Corporate Affairs has hitherto deregistered around 326,000 suspected shell companies9 and restricted their bank operations. Lists of over 300,000 disqualified directors associated with these companies have also been provided. In addition, FIU-IND provided its reporting entities with lists of domestic companies known or suspected by the LEAs to be shell companies, for relevant due diligence. These lists form an essential starting point for banks in their due diligence exercises.

Based on its risk-based policies, banks may conduct site visits for certain high-transacting customers to verify their underlying manufacturing/operating activity, office infrastructure, number of employees, awareness levels of directors and make neighbor/market inquiries to identify shells. Data-mining the existing customer base to locate entities operating from common addresses or linked via common contact details would also identify links across seemingly different entities.

For overseas shell companies, banks may undertake periodic in-house data analytics on their cross-border wire transfer report (CBWTR) data,10 to identify:

- a. Many-to-one or one-to-many transaction patterns involving common customer/counterparty

- b. Top “x” percentile of counterparties in terms of remittance values, good-wise or sensitive/higher-risk jurisdiction-wise, etc.

These counterparties could then be subject to due diligence via an open source intelligence search and/or obtaining their Dun & Bradstreet credit reports to check the following:

- Existence of company website

- Company address (whether it appears to be residential)

- Amount of registered capital

- Age of business

- Number of employees

- Fixed assets versus total assets

- Ownership details including principals (to identify related/connected parties)

- Scope and line of business

- Annual turnover/operating income

- Annual import/export values and countries/region of trade

A common pitfall is to implement the TBML RFIs as a separate framework/process, rather than into the main AML/CTF program

Trade Misinvoicing (Deliberate Over/Undervaluation of Goods)

The volume of illicit financial flows for developing countries in 2014 alone was estimated between $2 trillion and $3.5 trillion. Of this, an average of 87 percent was attributed to fraudulent trade misinvoicing.11

The $2.1 billion bank fraud in 2018 provides a classic example of how operational risk may manifest into

a money laundering scheme

Whilst it is widely acknowledged that bank personnel are typically not qualified to assess the true valuation of goods, regulators nevertheless expected them to conduct “reasonable” price checks while processing trade transactions. International best practices in this regard include the following:

- Formulating risk-based policies/procedures to guide staff, perform reasonable price checks from defined sources, acceptable price-variance thresholds (say, plus/minus 20 percent) varying across different goods/commodities and clear escalation paths when thresholds are exceeded

- Price checks by independent teams based on risk-based policy, e.g., based on sample/value thresholds, related parties, higher-risk goods/customers/countries

- Price checks for commodities, where market prices are generally available, subject to defined price-variance thresholds

- Price checks for goods, where market prices are generally not available, generally subject to identifying at least the significant, material, manifestly unusual, blatant or obvious pricing irregularities

- Implementing an in-house trade-pricing system. Suitable guidelines for selection of reference prices for goods/commodities may be formulated and reviewed periodically. In addition to market sources, inputs may be taken from valuation of trade transactions involving similar goods/commodities during the contemporary period (in-house data analytics), reputed customers of undoubted integrity, etc.

Pragmatically speaking, trade misinvoicing is a global issue necessitating integrated global measures. A World Customs Organization (WCO) report12 suggests collaborative partnerships of a country’s customs with the following:

- Trade businesses

- Other government agencies such as FIUs, tax and law enforcement

- Other customs administrators

International sharing of trade data facilitated by customs mutual assistance agreements between partnering countries, coupled with trade-data analytics (trade transparency units [TTUs]) help in identifying trade anomalies and possible TBML. TTUs examine trade by comparing, for example, Country X’s export records with corresponding import records from Country Y—any wide discrepancy could be indicative of TBML, meriting further investigation. The U.S. operates TTUs with 14 countries (excluding India), using a specialized computer system13 and more than $1 billion has since been seized.14 The Indian government could benefit by using similar data and analytics to systematically detect TBML.

Fraudulent Trade Documents

Past TBML schemes have typically involved the following:15

- Copies of the same BoE used for effecting multiple remittances via multiple banks

- Fake BoEs used for import remittances

- Fake foreign inward remittance certificates (FIRCs) used to regularize outstanding export advances, claim export-duty drawback

- Channelizing foreign exchange from one country to another by receiving inward remittances as export advances and remitting funds as advance import payments, without providing corresponding export/import evidences (shipping bills/BoEs), therefore exploiting trade-monitoring system weakness.

A significant initiative by RBI was the introduction of a comprehensive IT-based system digitizing Indian customs’ import/export data, namely the Import/Export Data Processing and Monitoring System (I/EDPMS). The system provides a secure online interface to all agencies involved in the import/export process, including Indian banks. Primary trade-data sourced daily from customs, special economic zones and software technology parks of India is shared with respective banks via an RBI-secured server, based on banks’ Authorised Dealer codes provided by importers/exporters. Banks update trade transactions daily and transaction status is visible to all system users on a real-time basis. Consequently, banks no longer rely on the physical BoE, shipping bill or FIRC documents, as these are available online. This reduces customs-related documentation frauds, aids trade-document simplification and improves trade transaction monitoring.

Regarding invoice fraud, banks are encouraged to develop suitable controls/processes, e.g., a bank in-house system to detect duplicate/multiple entries of the same invoice (number) keyed in for invoice financing/processing. Combating an industry-wide invoice-financing fraud16 necessitates technologies like blockchain to enable partnering banks using distributed-ledger-technology to detect submission of the same invoice across a joint-common platform.17 Finally, experienced and proficient trade-document checkers increase banks’ chances of detecting fraudulent documents.

Conclusion

As international trade continues to evolve in an ever-increasing digital landscape,18 sophistication and scale of TBML will undoubtedly increase. Effective countermeasures necessitate a comprehensive and global approach involving governments, FIUs, customs, tax and enforcement authorities—taking the fight against TBML much beyond banks with the application of risk-based, intelligence-led and targeted measures. Indian authorities’ efforts so far are laudable but more needs to be done, including establishing TTUs, strengthening Indian customs-audits19 and encouraging an ongoing formal public-private partnership,20 like the U.K. Joint Money Laundering Intelligence Taskforce or Singapore Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Industry Partnership, to share experiences, typologies and good practices to engender greater industry participation. Indian banks need to quickly plug their gaps and ensure their programs are “fit-for-the-purpose” to effectively combat TBML.

The views expressed in this article are those of its author and do not represent the views of his organization.

- “Trade Based Money Laundering,” Financial Action Task Force, June 2006, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/trade-basedmoneylaundering.html

- “Volume II: Money Laundering and Financial Crimes,” U.S. Department of State, 2009, https://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2009/vol2/index.htm

- Immediately following the scam, RBI undertook thematic trade-based audits at banks and imposed a combined penalty of IN$270,000,000 on 13 public/private sector banks for violating know your customer/AML/Foreign Exchange Management Act norms. It asked eight other banks to take steps to ensure strict compliance with such norms.

- RBI since undertook immediate action steps across Indian banks by soliciting letters-of-undertaking-(LoU)-related transaction/process details, discontinuing the LoU route and asking banks to comply with strict deadlines on more than a dozen checkpoints, most notably the integration of their core banking systems with the SWIFT gateway.

- “RBI’s statement on fraud in Punjab National Bank,” Reserve Bank of India, February 16, 2018, https://rbi.org.in/scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx?prid=43165

- In the $2.1 billion bank fraud, unauthorized LoUs were issued via SWIFT with the help of conniving branch employees without having any client sanctioned limits/collaterals (the branch’s core banking system was not integrated with SWIFT). The LoUs were contingent liabilities, i.e., undertakings by the issuing bank to repay buyer’s credit (short-term loans advanced by overseas banks for imports into India). All internal controls on the issuance/reconciliation of LoUs, i.e., maker-checker of LoU SWIFT messages, and reconciliation of confirmation advices from the funding bank and of buyer’s credit funds received in the bank’s Nostro account were compromised as operational controls at the bank were non-existent/inadequate.

- “Enforcement Directorate raids shell firms nationwide,” The New Indian Express, April 1, 2017, http://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2017/apr/01/enforcement-directorate-raids-shell-firms-nationwide-1588669.html

- Government measures include the passing of the Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Act, 2015, The Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2016, the demonetization of IN$1,000 and IN$500 denomination currency notes in November/December 2016, amending the “proceeds of crime” definition in the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) in 2015 to include “property equivalent held within the country” in case proceeds of crime is taken out or held “outside the country,” and the inclusion of corporate frauds and making false declarations or providing false documents to customs officials (albeit above IN$10,000,000) as scheduled offenses under PMLA.

- Section 248 of the Companies Act 2013 authorizes the Registrar of Companies to strike off a company from the register of companies when the company has failed to commence business within one year from the date of its incorporation or upon notice to the company and the directors where the company has failed to carry on business for two financial years and has not applied to obtain the status of dormant company.

- The FIU-IND has required its reporting entities to furnish it with a monthly CBWTR report of all cross-border wire transfers of the value of more than IN$500,000 or its equivalent in foreign currency where either the origin or destination of fund is in India.

- “Illicit financial flows to and from developing countries: 2005-14,” Global Financial Integrity, April 2017, https://www.gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GFI-IFF-Report-2017_final.pdf

- “Illicit Financial Flows via Trade Mis-invoicing,” World Customs Organization, 2018, http://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/media/newsroom/reports/2018/wco-study-report-on-iffs_tm.pdf?la=en

- The U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement operates TTUs using a specialized computer system called the Data Analysis and Research for Trade Transparency System.

- John A. Cassara, Trade-Based Money Laundering: The Next Frontier in International Money Laundering Enforcement, 2016.

- At the time of writing, reports surfaced on the use of counterfeit bills by unscrupulous elements to claim input tax credits fraudulently, i.e., refund of the Goods and Services Tax. As reported in local media, the government is presently working on creating a fraud analytics infrastructure for indirect taxes, which entails building a risk-profile of the taxpayer using information on sales/purchases, links with suspect firms, dealing in sensitive commodities, etc. It is expected that the introduction of an e-way bill (tracking movement of goods) and an invoice-matching system will enable the detection of fraudulent claims.

- For example, the multi-million dollar invoice financing fraud at China’s Qingdao port in 2014.

- Chanyaporn Chanjaroen, “Fraud in $4 trillion trade finance turns banks to digital ledger,” Livemint, May 23, 2016, https://www.livemint.com/Industry/CXfxl1yePlwTDuokXU3c2K/Fraud-in-4-trillion-trade-finance-turns-banks-to-digital-le.html

- Bloomberg news reported on May 24, 2018, that a shipment of soybeans from Argentina to Malaysia was backed by a blockchain-based letter of credit with the electronic exchange of trade documents completed within 24 hours!

- As per the WCO report (see footnote 12) it is important to ensure customs have a sufficient mandate (to detect all types of trade misinvoicing; traditionally, checks have been primarily conducted to detect underinvoicing of imports and resultant customs duties evasion) and resources (provide capacity building).

- The Indian government has already formed a high-level public-sector panel in 2014 comprising the director general (DG) of the Central Economic Intelligence Bureau, DG of the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence, Enforcement Directorate, director of the FIU-IND and the investigation wing of the Central Board of Direct Taxes. The panel’s mandate is to study modalities of TBML and devise indicators, methods and models for combating TBML. Further, the FIU-IND constituted a working group comprising the private sector and Indian public/private sector banks to study and formulate TBML RFIs and related guidance in India.