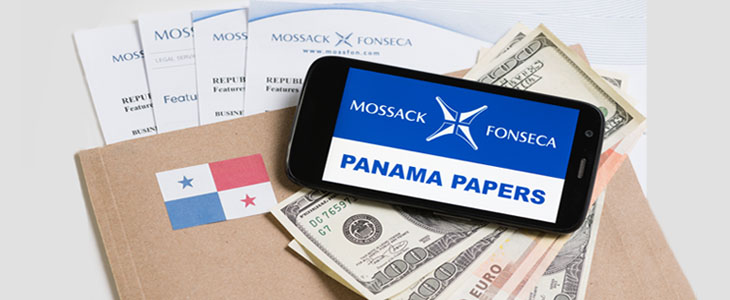

Forty years’ worth of records leaked to The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) involving 11.5 million documents pertaining to the creation of over 214,000 offshore shell companies by the fourth largest offshore law firm in the world, Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm with 600 employees and over 35 global locations from Nevada to Singapore.

The leaked documents allegedly tie various world leaders, billionaires, celebrities, possible drug dealers, Ponzi scheme artists and money launderers to Mossack-created shell companies that may have been used to hide illicit or corrupt funds or simply to illegally evade paying taxes. According to the ICIJ and various news articles, approximately 140 politicians (or their associates), located in 42 different countries, are connected to these offshore accounts, including:

- The prime minister of Iceland, who just resigned over the scandal;

- The president of Russia’s boyhood friend and other associates;

- The king of Saudi Arabia;

- The king of Morocco;

- The president of Ukraine;

- The president of Argentina;

- The children of the president of Azerbaijan;

- The son of the former president of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak;

- The late father of the current prime minister of England;

- The family of the late Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi;

- The sons of the prime minister of Pakistan;

- The family of China’s top leader; and

- Eight of the current or former members of China’s Politburo Standing Committee.

With regard to the recently resigned prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson claimed that the interest in the Mossack offshore account really belonged to his wife. As set forth in news articles, the account held millions of dollars’ worth of bonds from three giant Icelandic banks that failed in the 2008 financial crisis. The prime minister was on the account at one point, but released his interest to his wife for $1—hardly the market value. In addition, the prime minister himself was responsible for negotiating a settlement for the creditors of the banks, in which, obviously, he had a personal, vested interest. But he did not bother to disclose these minor facts and did not deem it necessary to recuse himself from a matter that was potentially going to net his family millions of dollars.

With regard to Russian President Vladimir Putin, his boyhood friend, concert cellist Sergei Roldugin, had a Mossack-created offshore account that allegedly had hundreds of millions of dollars flowing through it, but has described himself as “just a humble musician.”1 Clearly, he is no Yo-Yo Ma and, presumably, does not have millions of dollars of his own, so this account is suspicious. Furthermore, it has been reported that nearly $2 billion has passed through various Mossack-created offshore accounts for other friends and acquaintances of Putin’s between 2008 and 2013.2 Putin denies any wrongdoing, but this is an awful lot of money.

In addition to the politicians and world leaders, the Mossack firm allegedly created offshore accounts for a company that supplied fuel for an aircraft that the Syrian government used to kill its own citizens. Another account was allegedly created for a person who was convicted of laundering money from the 1983 gold heist at Heathrow Airport in which 7,000 gold bars, diamonds and cash were stolen from a warehouse (most of which has never been recovered). And there were even accounts for officials and players associated with the now-tainted worldwide soccer organization, Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA). There is even an alleged tie to a $50,000 payoff in connection with the Watergate scandal from the 1970s.

In addition to all of this, the leaked documents have led to investigations in numerous countries, including Britain, France, Italy, Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand.3

Very troubling to the banking world is the fact that approximately 500 banks since the 1970s have worked with the Mossack firm and the thousands of offshore accounts the firm created. In addition, the news accounts indicate that over 14,000 banks, law firms, company incorporators and other middlemen have worked with the Mossack firm in establishing the offshore accounts. This, of course, raises questions as to where the banks and the various “gatekeepers” (attorneys, company incorporators, etc.) were when these thousands of suspicious accounts were created and the ensuing transactions were conducted. According to the reports, the banking giant, UBS, set up more than 1,100 offshore companies through Mossack and HSBC set up more than 2,300. So, this scandal is not likely to stop at one, heretofore unknown, law firm headquartered in Panama. This scandal, unfortunately, will likely reverberate throughout the banking world.

However, all of this is not a new issue. This case involves the legitimacy and risk pertaining to the use of shell companies. While the majority of shell companies are used for legitimate purposes, including estate and tax planning, back in 2006, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of the Department of the Treasury issued an Advisory “to remind financial institutions of the importance of managing the potential risks associated with providing financial services to shell companies.”4 FinCEN issued the Advisory because, as set forth in the Advisory: “The potential to abuse shell companies for illicit activity must be recognized, and financial institutions must be vigilant in monitoring such companies on an ongoing basis. Financial institutions are expected to assess the risks involved in each shell company relationship and take steps to ensure that the risks are appropriately and effectively identified and managed in accordance with their BSA obligations.”5

According to FinCEN, in another report, the artificial nature and lack of direct business activity of shell companies, coupled with their lack of transparency, make them “inherently vulnerable to abuse.”6 In November 2006, this was echoed by the then-Chairman of the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI), Senator Norm Coleman: “Although the vast majority of these [shell] companies are formed to serve legitimate commercial purposes, the potential for abuse is great.”7 In addition, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has similarly weighed in: “Shell corporations and nominees are widely used mechanisms to launder the proceeds from crime . . .”8 This was stressed in the written statement submitted by FinCEN at the PSI Hearing:

“[A]s noted in the 2005 U.S. Money Laundering Threat Assessment, shell companies have become common tools for money laundering and other financial crime, primarily because they are easy and inexpensive to form and operate, and because ownership and transactional information on these entities can be concealed from regulatory and law enforcement authorities.”9

This conclusion was reiterated by the then-Chairman of the PSI at the November 2006 Hearings: “U.S. shell companies have been used to obscure the ownership and purpose of billions of dollars in international wire transfers and to facilitate criminal activity throughout the world.”10 As explained in the Executive Summary of the FinCEN report:

“By virtue of the ease of formation and the absence of ownership disclosure requirements, shell companies . . . are an attractive vehicle for those seeking to launder money or conduct illicit activity.”11

Thus, the overall problem stems from a lack of disclosure of the true beneficial owners of a shell company, which FATF addressed in its Recommendation 24:

“Countries should ensure that there is adequate, accurate and timely information on the beneficial ownership and control of legal persons that can be obtained or accessed in a timely fashion by competent authorities.”

The typical concern with regard to shell companies is directed at overseas or offshore companies. As set forth in an article in The Economist:

“Some [offshore financial centers] have rules that make it very difficult to exchange information with foreign enforcement authorities. Others do not register the companies that set up on their shores, so could not provide such information even if they wanted to. Cayman does register its offshore companies, of which it has over 70,000, and willingly assists foreign law-enforcement agencies, but it does not require companies to disclose their beneficial owners so the information is not all that helpful.”12

However, the problem is in the U.S. as well. Usually, certain states, like Delaware and Nevada, are singled out as being overly lax. But the truth of the matter is that only four states, at most, in the entire country ask for some kind of beneficial ownership information. And, even then, these states do not verify the information. So one can put down Donald Duck as the beneficial owner of the shell company and no state will ask about it or try to verify the information.13

The incorporation of shell companies is easy and relatively anonymous and, as a result, banks cannot rely on the states to provide them with the information necessary to even begin to perform adequate due diligence with regard to shell companies. As concluded in the FinCEN report:

“Therefore, 47 jurisdictions in the U.S. exist in which ownership of an LLC may legally remain unreported, depending on how the LLC is structured... [T]he conclusion does not address the potential for concealing identity through the use of nominees or similar mechanisms.”14

As stated by the Department of Justice in the same vein:

“In sum, a person from within or outside of the US, without any verification of identification, can submit the appropriate paperwork to form a corporation, and establish a corporation within as little as five minutes. The corporation is then a legal entity that can engage in business and open a bank account. Yet, some of the most important information about the corporation—its ownership—is nowhere recorded. If that corporation were to engage in fraudulent or negligent activity, it would be very difficult, or even impossible to identify its beneficial owners.”15

This lack of transparency is particularly troublesome and poses difficulties for the banking industry, as noted by then-PSI Chairman Norm Coleman:

“The absence of ownership disclosure requirements and lax regulatory regimes in many of our states make U.S. shell companies attractive vehicles for those seeking to launder money, evade taxes, finance terrorism, or conduct other illicit activity anonymously.”16

So to be worried about just Panama and other offshore jurisdictions is not the answer.

In March 2012, FinCEN issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to address the issue of shell companies and, specifically, to require banks to obtain and verify information pertaining to beneficial owners. Almost two and a half years later, on August 4, 2014, FinCEN got around to issuing a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on the subject. But that is where it sits.

Something more needs to be done.

It is understood that the proposed FinCEN rule on beneficial owners will greatly increase the costs of AML compliance for financial institutions, but, without the assistance of the 50 states and of foreign jurisdictions, there may not be any other viable alternative to protecting against the misuse of shell companies like those disclosed in the Panama Papers.

- Editorial Board, “The Panama Papers: Where has Russia’s billions gone?,” The Washington Post, April 4, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/where-have-russias-billions-gone/2016/04/04/44ebd46a-fa9a-11e5-80e4-c381214de1a3_story.html

- Ibid.

- Brian Murphy and William Branigin, “Iceland’s premier offers to step down,” The Washington Post, April 6, 2016, http://www.pressreader.com/usa/the-washington-post/20160406/281517930270324/textview

- “Potential Money Laundering Risks Related to Shell Companies,” Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, FIN-2006-G014, November 9, 2006, https://www.fincen.gov/statutes_regs/guidance/html/AdvisoryOnShells_FINAL.html

- Ibid.

- “The Role of Domestic Shell Companies in Financial Crime and Money Laundering: Limited Liability Companies,” FinCEN, November 2006, https://www.fincen.gov/news_room/rp/files/LLCAssessment_FINAL.pdf

- “Opening statement of Norm Coleman, Chairman, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations,” November 14, 2006, http://www.hsgac.senate.gov//imo/media/doc/OPENINGCOLEMANFinal0.pdf?attempt=2

- Written statement of Stuart Nash, Associate Deputy Attorney General, United States Department of Justice, before the PSI, November 14, 2006, pages 21-22.

- Written statement by Jamal El-Hindi, Associate Director for Regulatory Policy and Programs, FinCEN, before the PSI, November 14, 2006, page 2. See also, FinCEN Advisory, page 2.

- Coleman opening statement, page 2.

- FinCEN Report, page 2.

- “Unintended consequences: The less obvious uses of tax havens,” The Economist, February 22, 2007, – http://www.economist.com/node/8695233

- 2006 GAO Report, Highlights.

- FinCEN Report, page 9.

- Department of Justice written statement before the PSI, pages 4-5.

- Coleman opening statement, page 1.