On October 19, 2021, North Korea tested a submarine-launched ballistic missile. This was North Korea’s most provocative step since U.S. President Joe Biden took office, notable for two reasons. First, the ballistic missile can travel a long distance, exposing South Korea and Japan to the threat. Second, it is harder for missile defense systems to detect submarine-launched missiles.1 The next day, the United Nations (U.N.) Security Council met for emergency consultations. Pyongyang reacted by saying that the U.S. and U.N. are “tampering with a dangerous time bomb.”2

North Korea, the most sanctioned country in the world, continues to advance its nuclear and missile programs. With about 45 nuclear weapons already in possession, Pyongyang has enough nuclear material to build a few additional weapons. North Korea also has missiles that can fly ranges up to 13,000 kilometers, meaning North Korean missiles can reach targets on the U.S. mainland. Some believe North Korea is also working on perfecting the miniaturization of its nuclear warheads to mount them on missiles.3

North Korea attracts the most attention regarding the proliferation threat, but it is not alone. Over the past few decades, Iran’s nuclear and missile programs raised concerns within the international community. In investigating possible military dimensions of Iran’s nuclear program, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) concluded that Iran had a nuclear weapons program between 1999 and 2003. In 2005, Iran, the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council (China, France, Russia, the U.K. and the U.S.) and Germany reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that spelled out restrictions on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. But following the U.S.’ exit from the JCPOA in 2018 and the reimposition of U.S. sanctions, Iran has started rolling back on its commitments in the nuclear field.

Proliferation risks should not be synonymous with just North Korea and Iran. New countries might decide to acquire illicit weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs. Moreover, nonstate actors have shown their interest in WMD. For example, in 1995, the religious cult Aum Shinrikyo used sarin gas to attack commuters of a Tokyo metro, injuring 5,800 and killing 13 people. Terrorist organizations, such as al-Qaida and the Islamic State (IS), have also expressed interest in acquiring WMD.

As it is nearly impossible to procure ready-made WMD, the components, material and technology are what help build these weapons that are coveted by proliferators. Many are dual-use, have nonmilitary purposes and are available on international commercial markets.

Export controls regulate who can buy sensitive goods and under what conditions. Such controls make it more challenging but not impossible for proliferators to go on shopping sprees. Proliferators find ways to trick the system by pretending to buy controlled goods for legitimate purposes. Cutting proliferators’ access to financial services—fundraising, moving funds, paying for procurement—is another tool that can help minimize proliferators’ illicit activities. This article will cover recent changes in FATF Recommendations on proliferation financing and use North Korea as a case study of the challenges the international community faces with implementing proliferation financing controls on the ground.

“Soft Law”: Recent Revisions to the FATF Recommendations

International legal obligations for implementing proliferation financing-relevant controls mainly come from the U.N. Security Council Resolutions and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations, as well as unilateral sanctions regimes.

The U.N. Security Council maintains a broad sanctions regime against North Korea to curb North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs

There have been no changes in relevant U.N.-imposed obligations in recent years. The U.N. Security Council maintains a broad sanctions regime against North Korea to curb North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. When it comes to Iran, the U.N. Security Council lifted nuclear sanctions in the aftermath of the JCPOA in 2015. Still, it continues to restrict Iran’s ballistic missile-related activities. In addition, the U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540 (2004) obligates all U.N.-member states to maintain proliferation controls to prevent nonstate actors from acquiring WMD.

FATF Recommendation 7 states that “Countries should implement targeted financial sanctions to comply with United Nations Security Council resolutions relating to the prevention, suppression and disruption of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and its financing.”4 This requirement represents only a part of the obligations established by the U.N. Security Council Resolutions. First, Recommendation 7 in its current form does not reflect U.N. Security Council Resolutions on Iran and North Korea in their entirety by limiting the requirement to the “targeted financial sanctions” component. Second, Recommendation 7 does not account for potential proliferators who are not designated or might work on behalf of countries other than Iran and North Korea. Third, Recommendation 7 does not account for U.N. Security Resolution 1540, which does not mention any specific proliferate states.

U.N. resolutions represent hard international law, and all U.N. member states (i.e., practically all countries) must implement them. Yet, the implementation among countries is uneven—in most cases, due to lack of capacity and, in some cases, lack of political will.

Unlike the U.N. Security Council resolutions, FATF Recommendations represent “soft law,” but they carry substantial weight due to FATF’s ability to “name and shame” the noncomplying countries. As a result, the recent changes to Recommendations 1 and 2 to incorporate proliferation financing components are consequential for financial crime prevention and nonproliferation. FATF adopted changes to Recommendations 1 and 2 in October 2020 and published a revised set of Recommendations in June 2021.

The most substantial change involves Recommendation 1. Previously, Recommendation 1 focused on risk assessment and risk-based approach as applied to money laundering and terrorist financing. After the change, “[c]ountries should also identify, assess, and understand the proliferation financing risks for the country,” and “[c]ountries should require financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) to identify, assess and take effective action to mitigate their money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing risks.”5 FATF clarifies this in the context of Recommendation 1, “proliferation financing risk” to the potential breach, nonimplementation or evasion of targeted financial sanctions referred to in Recommendation 7. As discussed earlier, from the nonproliferation point of view, interpreting “proliferation financing” as equivalent to targeted financial sanctions related to Iran and North Korea is too limited.

The revised Recommendation 2 now also includes a reference to proliferation financing: “Countries should have national AML/CFT/CPF policies, informed by the risks identified, which should be regularly reviewed, and should designate an authority or have a coordination or other mechanism that is responsible for such policies.”6

Risk Assessment

Almost simultaneously with the revised Recommendations, FATF released “Guidance on Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment and Mitigation.” While the guidance comes with a reminder that proliferation financing in the FATF context refers only to targeted financial sanctions against Iran and North Korea, its substance helps assess broader proliferation financing risks and has plenty of actionable, practical advice.

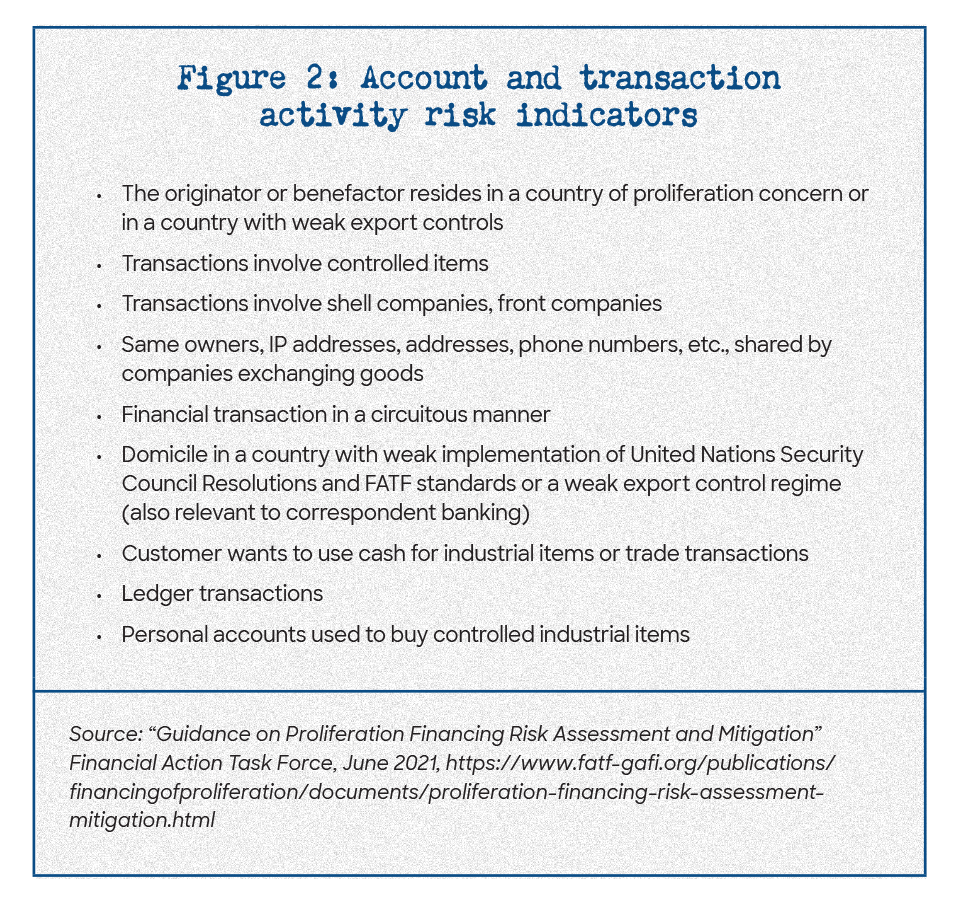

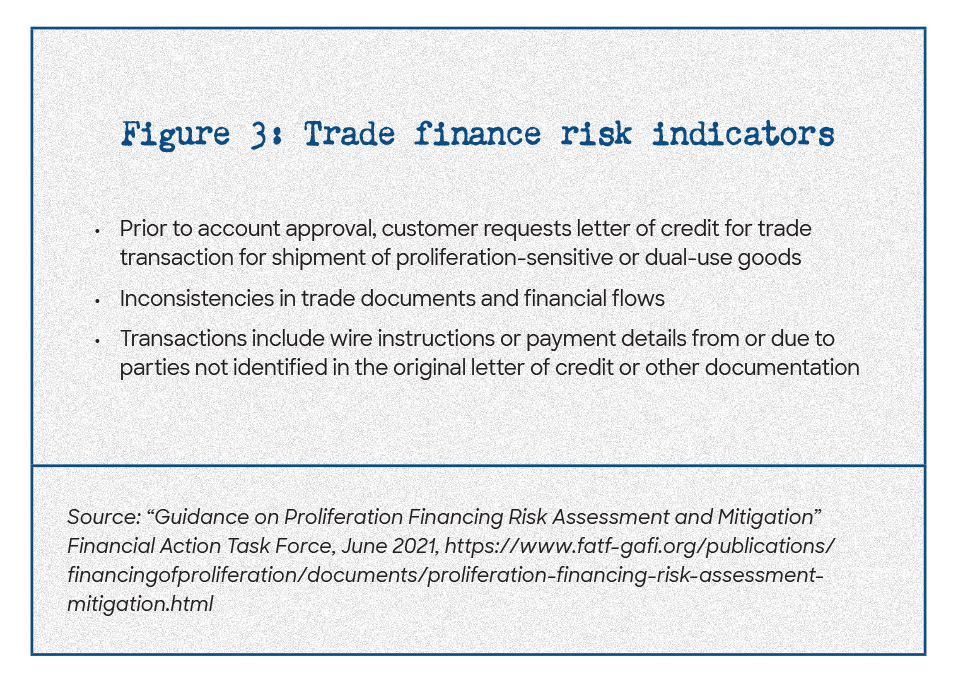

One of the useful features of the guidance is the provision of category-specific risk factors, such as risk factors associated with customer profile, trade finance risk factors or risk factors specific to virtual asset providers, to name a few. The guidance is helpful for public and private sectors and includes advice to supervisors and self-regulatory bodies responsible for ensuring proper assessment and mitigation of proliferation financing risks (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

The public consultation process prior to the adoption of the revised FATF Recommendations stimulated discussion on de-risking and challenges for financial inclusion in the process of expanded risk assessment.7 FATF itself emphasizes stakeholders should execute new obligations in a manner that is proportionate to the risks identified to avoid contributing to de-risking or financial exclusion.8

Even before FATF added proliferation financing risk assessments to its Recommendations, several jurisdictions conducted their national proliferation financing risk assessments either as a stand-alone assessment or as part of a broad national risk assessment (money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing). The jurisdictions that made their assessments public include the U.S.,9 the Cayman Islands,10 Gibraltar,11 Latvia,12 Portugal,13 Namibia14 and the United Kingdom (U.K.).15 These can be useful for jurisdictions considering conducting their national risk assessments in the near future. In addition, the U.K.’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) developed “Guide to Conducting a National Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment”16 and made it publicly available.

On the Ground: The Case of North Korea

Four factors make North Korea a useful case study to understand how proliferation financing works on the ground. First, North Korea continues to advance its nuclear and missile capabilities with the help of goods and technology procured overseas, which makes it an active proliferator state. Second, as the U.N. sanctions regime extends to both procurement and revenue generation, North Korea’s case is most straightforward when it comes to a broader interpretation of “proliferation financing.” In its case, “proliferation financing” can be interpreted to include both illicit procurement and fundraising. Third, North Korea is one of the most notorious and successful sanctions evaders. Finally, thanks to the U.N. Panel of Experts, which tracks North Korea sanctions implementation, there are rich data points about North Korean agents’ operations and techniques.

The global COVID-19 pandemic slowed down some of North Korea’s sanctions evasion activities but did not eliminate them. As the world gradually returns to a more active trade environment, more sanctions busting and sanctions evasion from North Korea can be expected. Meanwhile, North Korea continues to have access to the international financial system despite broad U.N. restrictions. Below are Pyongyang’s most common illicit activities that have a direct bearing on FIs.

Access to the International Financial System

North Korea’s tried and tested methods to exploit FIs of third jurisdictions include stationing its banking representatives overseas, using shell companies, exploiting opaque corporate registry processes to hide beneficial owners, conducting illicit trade with the help of trade financing services and using correspondent accounts in FIs of third countries to conduct transactions in U.S. dollars. According to the information received by the U.N. Panel of Experts, dozens of North Korea’s bank representatives were operating in third jurisdictions as of 2020.17

Maritime Industry

The U.N. prohibits North Korea from exporting coal, sand, weaponry and many other items. The goal is to cut its revenue-generating stream and reduce funding available for financing its nuclear and missile programs and propping up the regime. The U.N. also prohibits North Korea from importing goods ranging from dual-use goods to luxury items. Despite U.N. prohibitions, North Korea exploits the maritime industry for illegal exports and imports. It manipulates vessel identification and detection by, for example, switching off or manipulating automatic identification system (AIS) signals, physically changing vessels’ appearances or “laundering” vessels’ identities.

For example, the most recent U.N. Panel of Experts report describes the case of a vessel called Billions No. 18 (aka Kingsway). The U.N. designated Kingsway in 2017, but it continued to sail undetected and transmit AIS signals as the Mongolia-flagged Apex (aka Shun Fa). Shun Fa’s registered International Maritime Organization (IMO) number belonged to the Mongolia-flagged Apex. The IMO number on the vessel was physically manipulated. Until the identity disguise was confirmed and one of the U.N. member states impounded it in May 2021, the vessel continued to operate and access financial services.18

Activities in the Crypto Domain

North Korea demonstrates an increasingly sophisticated and active use of the crypto domain for its revenue-generating and laundering activities. As virtual assets providers remain less regulated than formal FIs, they are more susceptible to illicit use. For example, cryptocurrency exchanges have varying levels of know your customer procedures. Some categories of cryptocurrency are less traceable than others. In addition to mining cryptocurrency, agents working on behalf of North Korea steal from cryptocurrency exchanges and individual users. One of the popular methods used by North Korean agents is to conduct spear-phishing campaigns against potential targets. So far, there have been no confirmed cases of North Korea or others using cryptocurrency to procure sensitive goods. The main challenge right now is fundraising in the crypto domain. In 2021, the U.S. Justice Department unveiled charges against three North Koreans who were accused, among other things, of participating in the theft of tens of millions of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency, including $75 million from a Slovenian cryptocurrency company, $24.9 million from an Indonesian cryptocurrency company; and $11.8 million from an American financial services company.19

Conclusion

North Korea keeps the international policy community on its toes and manages to advance its nuclear and missile programs, despite the sanctions. It does it with the inadvertent help of the global financial community. FATF’s growing attention to proliferation financing, despite the limitations of its Recommendations, are a welcome development.

Togzhan Kassenova, Ph.D., CAMS, senior fellow, Project on International Security, Commerce, and Economic Statecraft (PISCES), Center for Policy Research at University at Albany-SUNY; nonresident fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, D.C., USA, tkassenova@albany.edu

- “North Korea Fires Suspected Submarine-Launched Missile Into Waters off Japan,” BBC News, October 19, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58963654

- Yoonjung Seo, Samantha Beech and Philip Wang, “North Korea Accuses US and UN of ‘Tampering With a Dangerous Time Bomb,’” CNN, October 21, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/20/asia/north-korea-time-bomb-un-us-intl-hnk/index.html

- David E. Sanger, William J. Broad, Choe Sang-Hun, “Biden is Facing an Uneasy Truth: North Korea Is Not Giving Up Its Nuclear Arsenal,” New York Times, May 20, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/20/us/politics/biden-north-korea-nuclear-weapons.html; “North Korea: What We Know About Its Missile and Nuclear Program,” BBC, October 4, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41174689; Julia Masterson, “UN Experts See North Korean Nuclear Gains,” Arms Control Today, September 2020, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-09/news/un-experts-see-north-korean-nuclear-gains.

- “FATF Recommendations,” Financial Action Task Force, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/fatfrecommendations/documents/fatf-recommendations.html

- Ibid; “Public Statement on Counter Proliferation Financing,” Financial Action Task Force, October 23, 2020, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/financingofproliferation/documents/statement-proliferation-financing-2020.html

- Ibid.

- Louis de Koker, “Financial Action Task Force Standards and Financial Inclusion: What Should Be Done – and What Should Not Be Done – to Improve the Alignment Between Integrity and Inclusion Policy Objectives?” La Trobe Law School, August 23, 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3679779

- “Guidance on Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment and Mitigation,” Financial Action Task Force, June 2021, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/documents/guidance/documents/proliferation-financing-risk-assessment-mitigation.html?hf=10&b=0&s=desc(fatf_releasedate)

- “National Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/2018npfra_12_18.pdf

- “Results of the 2015 Cayman Islands National Risk Assessment Relating to Money Laundering, Terrorism Financing and Proliferation Financing,” Department and Labour & Pensions, 2015, http://www.dlp.gov.ky/portal/pls/portal/docs/1/12408457.PDF

- “2020 National Risk Assessment for AML/CFT and PF,” HM Government of Gibraltar, August 2020, https://www.gfiu.gov.gi/uploads/docs/Ihhoj_2020_NRA_Final.pdf

- “National ML/TF/PF Risk Assessment 2017-2019 (Executive Summary),” Finanšu izlūkošanas dienests, 2020, https://www.fid.gov.lv/uploads/files/2021/NRA_2017_2019_Executive_Summary%20%28002%29.pdf

- “Portugal National Risk Assessment Money Laundering, Financing of Terrorism Proliferation Financing Summary,” Branqueamento de Capitais e Financiamento do Terrorismo, December 2019, https://portalbcft.pt/sites/default/files/anexos/nra_2019_-_summary.pdf

- “2020 NRA,” Financial Intelligence Centre Republic of Namibia, https://www.fic.na/index.php?page=2020-nra

- “National risk assessment of proliferation financing,” HM Treasury, September 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1020695/National_risk_assessment_of_proliferation_financing.pdf

- Anagha Joshi, Emil Dall and Darya Dolzikova, “Guide to Conducting a National Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment,” Royal United Services Institute, April 6, 2019, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/guide-to-conducting-a-national-proliferation-financing-risk-assessment

- “Midterm Report of the Panel of Experts Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2569,” United Nations, September 2021, https://undocs.org/S/2021/777, 47.

- Ibid, 16.

- “Three North Korean Military Hackers Indicted in Wide-Ranging Scheme to Commit Cyberattacks and Financial Crimes Across the World,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 17, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-north-korean-military-hackers-indicted-wide-ranging-scheme-commit-cyberattacks-and