In January 2021, the passage of the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA) was greeted with near jubilation by the anti-financial crime (AFC) community. Since then, regulations implementing the AMLA, specifically the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) portion, have gotten a mixed reception from AFC professionals.

The act and the Financial Crime Enforcement Network’s (FinCEN) enabling regulation will ultimately create a database of corporate ownership, beginning in January 2024. For the first time, federal law enforcement (LE), national security and intelligence agencies, and federal regulators will have direct access to beneficial ownership information in the context of “investigative and enforcement activities relating to civil or criminal violations of law,” which covers a broad set of circumstances.1

As with all legislation, however, compromises were made to pass the CTA between legislators who believed the public has a right to know who owns businesses operating in the U.S. and lawmakers who valued owners’ privacy rights over the public interest.

The result is that the FinCEN regulations greatly limit who will have access to the ownership database.

Among those with limited access are state, local and tribal LE officials. They must send FinCEN a copy of a “court order” that authorizes them to seek information, along with a written explanation of why their query is relevant to their case.2

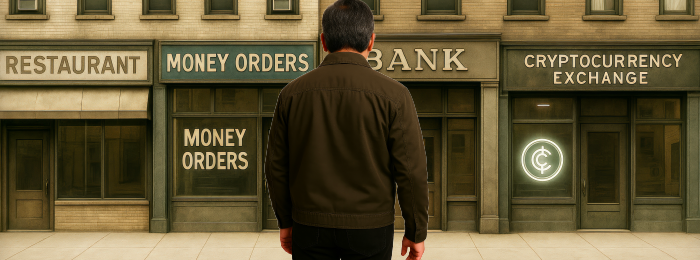

Financial institutions (FIs) will have to meet an even higher bar: They must obtain permission from clients to see a copy of their filing with FinCEN and they cannot share the ownership information they receive with foreign subsidiaries or foreign domiciled back offices. Banks are only authorized to request the ownership information to fulfill their customer due diligence duties and not in relation to their reporting responsibilities under the Bank Secrecy Act. Money services businesses, including virtual asset service providers, have no standing to request filings.

Neither state and local LE nor banks can query the database, for example, to connect a corporate owner to multiple filings of the companies in which they may also hold an interest.

In commenting on these limitations, the American Bankers Association (ABA) was critical of FinCEN, concluding that under its notice of rulemaking the database is “practically useless.” The February 14 missive to FinCEN, released on the last day of the open comment period and certainly no Valentine, called on FinCEN to scrap its “fatally flawed” proposal and start again.3

The public’s legitimate interest in corporate ownership transparency has been fueled by numerous documented abuses of shell companies. The Panama Papers and Paradise Papers showed how political leaders hid wealth, some of it stolen, and transnational crooks made the proceeds of their crimes disappear through opaque shell companies.4 The uncovering of illicit fund flows from Russia through the Baltic States, into Nordic banks, and into the global financial system via shell companies also furthered the push for transparency.5

The abuse of shell companies continues, most notably to evade sanctions, a fascinating case study of which is ACAMS Today’s cover story in this issue, “Russia’s Hope of Ice Hockey Glory Buried Under Sanctions.”

But the pushback on privacy grounds has been forceful.

European Union (EU) legislation for country-by-country ownership registries that would cascade into an EU-wide registry is being inconsistently implemented following an EU high court decision that full-public access violates privacy rights. The debate now centers on who should have access beyond “mere citizens,” with the possibility remaining that FIs, nonprofits and journalists will have access, which means the EU registries are likely to remain more accessible than the U.S. registry.6

A case can be made for certain ownership information remaining private under limited circumstances, but others will have to make it. Quoted repeatedly, for good reason, is U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’ remark that “sunlight is the best disinfectant” for public corruption and crime.

It is an accomplishment that the U.S. will have a national registry of corporate ownership available to some of the LE community. But unfortunately, as currently configured, much of that information will not in the largest sense see the light of day. That will require further legislation and regulation.

Kieran Beer, CAMS

Chief Analyst, Director of Editorial Content

Follow me on Twitter: @KieranBeer

“Financial Crime Matters with Kieran Beer”

- Benjamin Hardy, “Compliance Professionals, Former US Officials Debate FinCEN’s ‘Access’ Proposal,” ACAMS moneylaundering.com, February 9, 2023, https://www.moneylaundering.com/news/compliance-professionals-former-us-officials-debate-fincens-access-proposal/

- Ibid.

- “American Bankers Association Rejects FinCEN’s Latest Beneficial Ownership Plan,” ACAMS moneylaundering.com, February 14, 2023, https://www.moneylaundering.com/news/american-bankers-association-rejects-fincens-latest-beneficial-ownership-plan/

- “The Panama Papers: Exposing the Rogue Offshore Finance Industry,” The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, https://www.icij.org/investigations/panama-papers/

- Benjamin Hardy, “Danske Bank Settles Money Laundering Accusations After Deceiving US Banks,” ACAMS moneylaundering.com, December 13, 2022, https://www.moneylaundering.com/news/danske-bank-settles-money-laundering-accusations-after-deceiving-us-banks/

- Koos Couvée, “Months After Landmark Ruling, EU’s Ownership Databases Still Face Uncertain Future,” ACAMS moneylaundering.com, February 13, 2023, https://www.moneylaundering.com/news/months-after-landmark-ruling-eus-ownership-databases-still-face-uncertain-future/