As the world reflects two decades on from this horrific act of terrorism, questions remain as to whether the regulations that followed 9/11 made for a safer world, particularly when it comes to the complex issue of anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing. September 11 threw the U.S. intonational security chaos, amplifying the need for quick and effective regulation. Given the extremity of the event, the solution was rolled out rapidly. However, despite the addition of the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA), the solution left, and continues to leave, much to be desired.

The direct response to the attacks was the USA PATRIOT Act, the act itself is a substantial piece of legislation that made considerable strides from an AML perspective—from strengthening banking rules against money laundering to providing a greater emphasis on financial institutions (FIs) and law enforcement communicating with each other. The issue is that the PATRIOT Act, and subsequent AML legislation, has failed to address the overall effectiveness of exactly what FIs have been doing around AML—including everything from information sharing to technology. The most sweeping change in 20 years since the passage of the PATRIOT Act has been the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA). The AMLA has taken numerous steps in modernizing AML regulations, but it remains to be seen how effective it will be in the fight against financial crime as the act’s various provisions will come into effect over the next few years.

There have been numerous examples of regulators reprimanding banks for not ticking boxes X,Y or Z. This is all well and good, but the problem is the way the legislation has been constructed and how it does not place weight on one area over another.

While there has been the publication of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Manual, starting in just three years after 9/11, along with regular guidance issued by government bodies such as the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), there has generally been a lack of focus, and overall guidance, on the actual effectiveness of an FI’s AML policy. Instead, laws and accompanying guidance have followed along more specific lines saying, “this bank is violating AML rules to the letter of the regulation” as opposed to looking at the bigger picture and saying, “does it actually matter if you do or do not check the right box,” having an in-depth understanding of client behavior and overall asking, “does this aid law enforcement in the prevention of criminal activity?” Today it is difficult to define the exact percentage of funds illicitly moving in and out of the global banking system, but it is generally accepted to be quite significant. Thus, there should be an even greater emphasis on the effectiveness of AML, the Bank Secrecy Act and subsequent AML regulations.

The trouble is the downside of noncompliance stretches much further than just being fined. Where fines may be a drop in the bucket for some larger sized banks, the reputational risk extends to an FI of any size. The reputational risk it can cause can be significant, with many understandably choosing to concentrate their efforts on protecting their reputation. In order to combat recent scandals—such as Pegasus spyware which demonstrated that where technology has developed, so has criminal sophistication—financial services providers must adopt a technology-first approach. By implementing the solutions quickly and integrating them easily, this will allow FIs to gain a faster insight into how to tackle AML regulation effectively. In the same way that 20

years on, criminals have moved to communicate in ways beyond a telephone line, FIs must adopt their own technology-based solutions. With these solutions in place, they will undoubtedly streamline the process to maximize efficiency. With the ever-changing regulatory environment, technological solutions force FIs to stay ahead of the regulatory curve. Artificial intelligence (AI), robotic process automation (RPA) and machine learning can create a single client view and enhance risk management across their organizations, ensuring fewer fines going forward.

Initiatives like the beneficial ownership registry, a significant portion of the AMLA, are going to help. Although numerous FIs are saying the initiatives have the potential to be great, are the initiatives just going to be a load of data shoved into a database that nobody can decipher? While this may not affect the large corporate clients of, say, a larger bank, it will present a massive administrative burden on a mid-tier bank with smaller corporate clients who will now have to work through copious amounts of additional paper work with a lot of repetition. By making this information and process automated, it can resolve the possibility of human error.

In addition to the beneficial ownership registry, the Panama Papers and FinCEN Files have unquestionably moved the needle in the right direction with regard to AML reform. Covering over 2,000 documents sent by banks to U.S. rule makers, the FinCEN Files at least shone a light on what clients might be doing, while the Panama Papers helped exposed the murky world of offshore finance. Looking back through all the rules that have come into force since 9/11, one has to say that they do not fully reflect the modern data challenges banks face around AML.

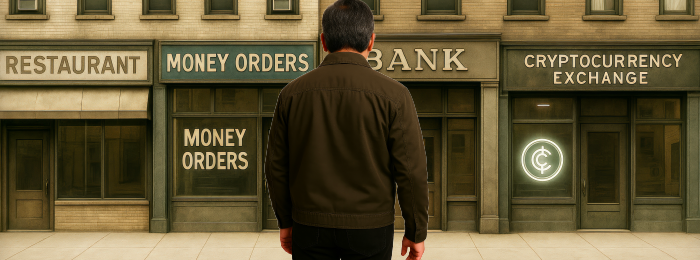

It is all well and good going through all the risk assessment requirements contained in the PATRIOT Act, but 20 years later, the world is a very different place. It is no longer just about people creating shell companies to launder their cash. The flow of dirty money to unquantifiable levels continues to grow as technology evolves and is used by bad actors to exploit the global financial system. With that, governments and FIs must evolve technologically to keep up. And when it comes to keeping up via the use of the technology, the devil is very much in the details. The tech needs to manage every single event that could impact a client's risk profile—from geographic location to the specific type of financial products being sold. In addition, due to the fact there is no singular regulatory framework that applies transnationally, there needs to be more of a focus on building and engaging task forces. While the Financial Action Task Force has seen their list of legislative recommendations mirrored in over 180 jurisdictions, including five individual European Union directives, there are still disparities in the underlying regulations on a country-by-country basis. Setting up and engaging directly with more global task forces must be considered as a solution, particularly for the small to mid-sized banks with smaller budgets. As the world reflects somberly 20 years on from 9/11, perhaps the only way to move forward is by emphasizing the overall effectiveness of regulation utilizing technology while adopting a risk-based approach. Preventing the cause as opposed to treating the infection and focusing on sharing information harvested by technology should provide both FIs and the federal government the tools, and crucially, the evidence to combat the global and constant flow of illegal money since the PATRIOT Act came into force.

By their very nature, AML regulations & reforms are so much conducive to geopolitics, national interest & security, malign activities of non-state actors, preserving financial integrity and other aspects of an interconnected digital world. We should make no mistake that within this evolving and fluid state, questions will always outweigh answers: yet we should always maintain our resolve and resiliency in disrupting illicit financial flows.