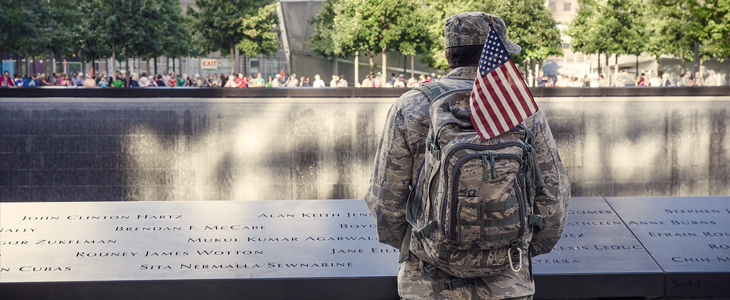

The attacks of September 11 radically transformed every aspect of life, business and governance, and its effects continue to be felt today. For members of the Armed Forces, the impact was immediate and drastic. A largely conventional force with a doctrine primarily geared for warfare amongst nation-states had to transform quickly and confront an enemy lacking borders, uniforms or national identity. The following is the story of two servicemen’s differing career paths to confront a new challenge, which led to a new focus on illicit finance and its relations to the fight against terror.

Brian Smith (Colonel, retired, U.S. Army)

The day the Twin Towers fell in New York City, I was a young army captain at Fort Riley, Kansas. I was eating breakfast at the dining facility when an airplane hit the first tower. I knew that my life—and military career—had changed tremendously that morning. I strongly suspected that I, and the rest of the military, would soon be called upon to do what we were trained to do—fight. The events of 9/11 forever changed the trajectory of my life and career.

I was an Army Finance officer who was about to learn just how interwoven military operations and economic and financial efforts really are for our military and those of the adversary.

Our finance unit, along with every other unit in the U.S. Army, began earnest training and preparations for deployment to the Middle East. We were eager to go, anxious to get our once-in-a-generation chance for a wartime experience that we thought would be measured in months. We did not want to miss out. To say that we grossly miscalculated the duration of the fight that we embarked upon would be a major understatement.

Less than two years later, in May 2003, my finance detachment pushed into western Iraq from Kuwait, attached to an Armored Cavalry Regiment, to occupy the Anbar province. Our unit mission was to conduct financial and cash operations supporting combat operations. I thought it would be a straightforward mission set from the financial perspective. It was anything but that.

I thought that my mission was to resource, pay for and disburse cash to pay for military operations. What I soon learned in Iraq was that I needed to understand, learn and adjust to the banking, financial and economic systems of my deployed location.

For context, in Iraq in May and June 2003, the entire banking system ceased to function due to political decisions made at the national level. The economic situation degraded rapidly and gave a spark to the insurgency that began to arise around us in Iraq. No money means no jobs nor the ability to conduct business outside of bartering for the civilian population.

I was soon called upon to go meet with the provincial governor and his banking chiefs. My directed mission was to “get the banking system back online”—not my normal military mission.

During the course of the next 20 years, I would deploy to Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan and also support unique mission sets within the special operations community in the Middle East. Each mission and deployment demonstrated the financial domain and the importance of understanding how value and money are raised, stored, moved and used to support our own operations—and those of the adversaries we fought. Seized or captured currency on the battlefield, indigenous banking systems, local economic dynamics, contract payments in cash and cash for Army operations were recurrent themes.

I deployed as a Colonel to Kabul, Afghanistan in 2019-2020 as a theater-level comptroller for a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) unit that was charged with funding and equipping the Afghan military—payroll, equipment, ammunition, maintenance, weaponry, aircraft and ground vehicles. My unit’s mission literally controlled, spent and budgeted for a multibillion-dollar budget. It became obvious that conducting know your customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD) was critical to safeguard our own disbursements to contractors and service providers in Afghanistan. We saw the positive and very negative effects of excessive amounts of cash injected into the operating area.

I culminated my military career working within the counter-threat finance and financial effects areas of military operations—understanding how the adversary or enemy does four things with resources: raise it, store it, move it and use it—and getting desired effects from that understanding. We also took a very close look at how the huge amounts of funding that U.S. and Coalition efforts injected into the operating environment perversely ended up benefiting adversaries such as the Taliban and the Islamic State group’s Afghanistan affiliate enterprises.

Charles Rego (Lieutenant, U.S. Navy Reserve)

On the morning of September 11, I had to travel to our unit quartermaster with my good friend Zubair Khan to retrieve some new uniforms for our team. I remember entering the warehouse and all four staff members were crowded around a television in a break room. There was an eerie silence; no laughter, no conversation, just four men keenly focused on the television. As Zubair and I approached, one of the quartermasters yelled, “Oh my God!” At that point, I saw the monitor and the explosion of the second aircraft on the towers. Immediately, my heart sank; I felt cold and numb and knew everything was about to change.

Terrorism was not new to me. On June 25, 1996, 12 members of my unit, the 33 Fighter Wing, perished when a truck bomb struck just outside the fence line of Khobar Towers. But I never imagined that carnage would ever reach us at home and at a scale that killed thousands. New York was my home, and I remembered gazing at the sheer size and awe of the towers as a young boy.

I left the quartermaster, called my fiancée and drove home to pack my bags. I did not know if I would be called, when I would be called or what I would do, but I did know the world just changed and I had to be ready for whatever came next.

My first few years after the attacks were spent working on counter-terrorism. It was new to all of us; very few people had experience in terrorism. A hodgepodge of law enforcement, counterintelligence agents, accountants, customs officials and military personnel worked quickly to prevent additional attacks and go after those who destroyed the towers. We had no time to learn a new threat, enemy or the tactics they employed. We only had time to act with what we knew, the training we had and the drive to prevent another attack in our homeland.

Over the course of more than 20 years, I have been deployed to Iraq, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Colombia and countless other countries, working alongside various partners to combat our shared foe. My work in counter-terrorism led me to the field of counter-threat finance and the military’s role in combating illicit finance. This was a new field that was not customary to an organization that was more duly suited for classic kinetic warfare. The military’s role in addressing illicit finance gave us a broader understanding of an enemy’s capabilities and weaknesses and a clearer understanding of their operations, structure and capabilities.

Conclusion

Smith and Rego both believe that ACAMS has been a key partner and educator for the counter-threat finance community throughout their journey in combating illicit finance. The organization, its access to key relevant education and its strong global network have been instrumental in broadening their expertise.

In addition, they both feel strongly about this requirement for knowledge, so strongly that they began to train and certify select soldiers and airmen with the Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialist (CAMS) certification to support future military operations.

Brian A. Smith, Colonel (Ret.), U.S. Army, ![]()

Charles Rego, COO of Invicurity LLC, U.S. Navy Reserve Officer, ![]()