This article is the third of a three-part series on human trafficking.

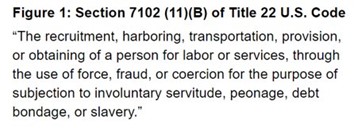

The first article of this three-part series, “Understanding Human Trafficking,”1 covered the definitions and terminology associated with human trafficking (HT), including the U.S. federal definition of labor trafficking.

Although sex trafficking is more widely discussed, it is estimated that there are over three times more victims of labor trafficking than there are victims of sex trafficking, as seen on Figure 2.2 Financial institutions (FIs) can work to identify labor trafficking through careful consideration of high-risk customers, expanded negative news, partnerships with account managers in relevant lines of business and by understanding key red-flag indicators.

Figure 2: Global Modern Slavery Index

Methods of Control

It is important to emphasize that in situations of labor trafficking, the abuse exceeds simple labor law violations. Rather than merely being an undesirable job; force, fraud and/or coercion are used to compel a person to work against their will.

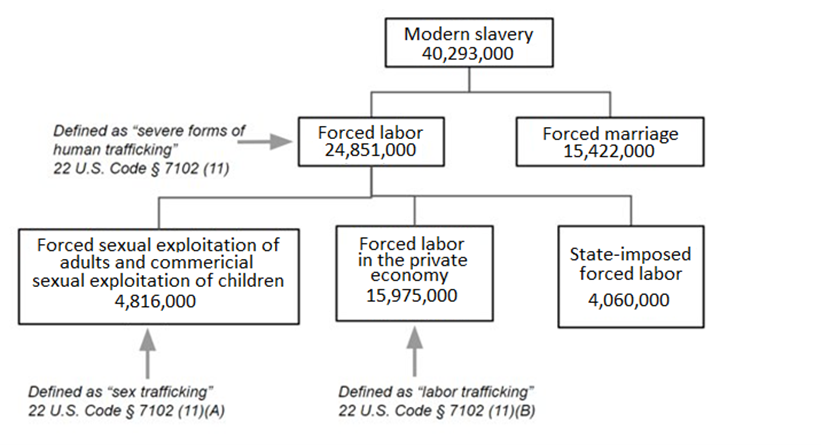

Labor trafficking situations often involve methods of control that can be particularly difficult to identify. Common methods of control include confiscating a worker’s identification documents, threats to report the worker to immigration/law enforcement, isolation and/or physical confinement, fraudulent recruitment practices and various forms of economic abuse. At least 60% of victims in situations of labor trafficking that were reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline since 2015 had experienced some form of economic abuse, including withholding wages or wage theft, debt bondage, threats to blacklist the victim from future employment in the industry or restricting a victim’s access to their financial resources (see Figure 3). This economic abuse may manifest as anomalies in a business’s financial records.

Figure 3: Common Methods to Control Victims

Source: Data from the National Human Trafficking Hotline Operated by Polaris

Understanding High-Risk Industries for Labor Trafficking

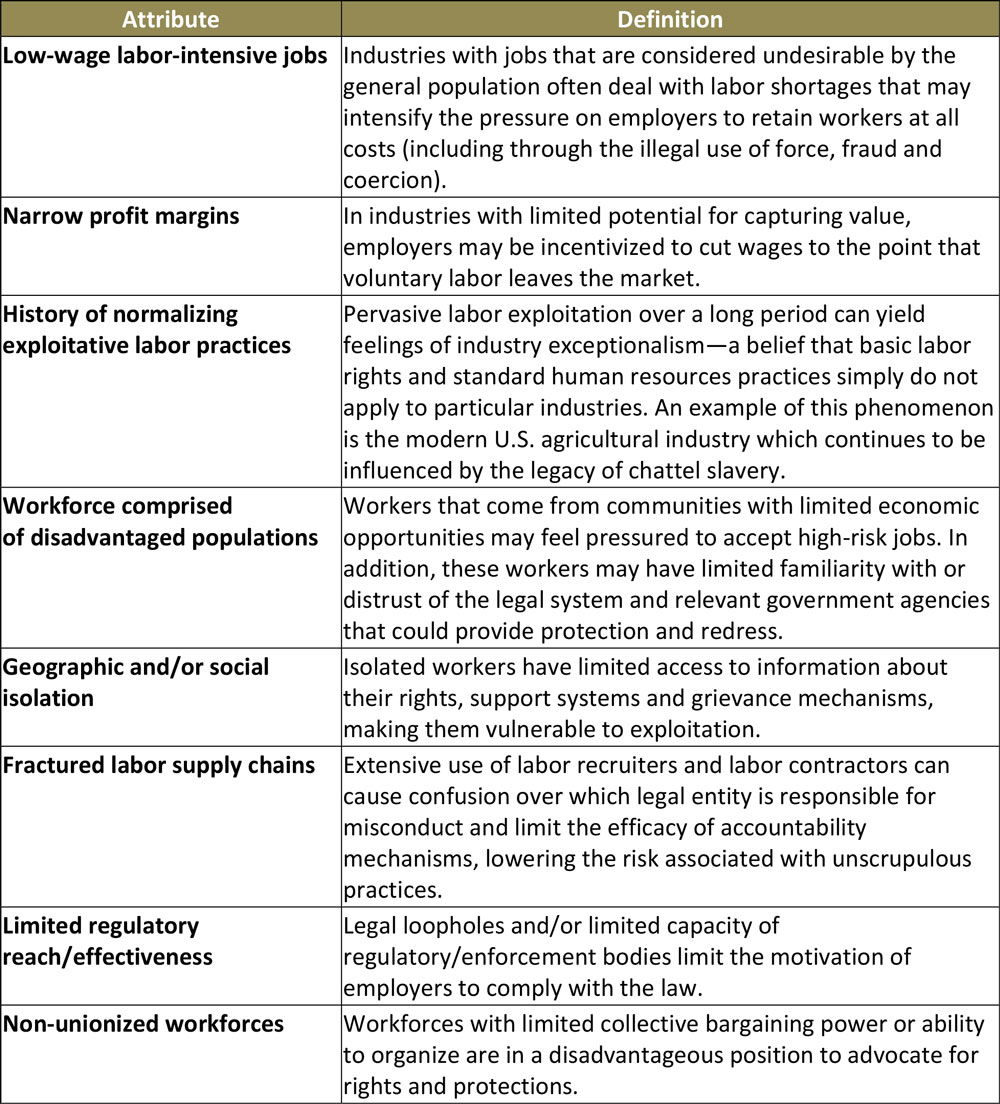

Industries with high levels of labor exploitation and trafficking vary widely by geography. However, if considering the market forces that may motivate an employer/manager to utilize methods of force, fraud and/or coercion to retain workers, some key characteristics emerge.3 By understanding these attributes, FIs will be able to identify high-risk businesses among their customers (see Table 1).

Table 1: High-Risk Industries for Labor Trafficking

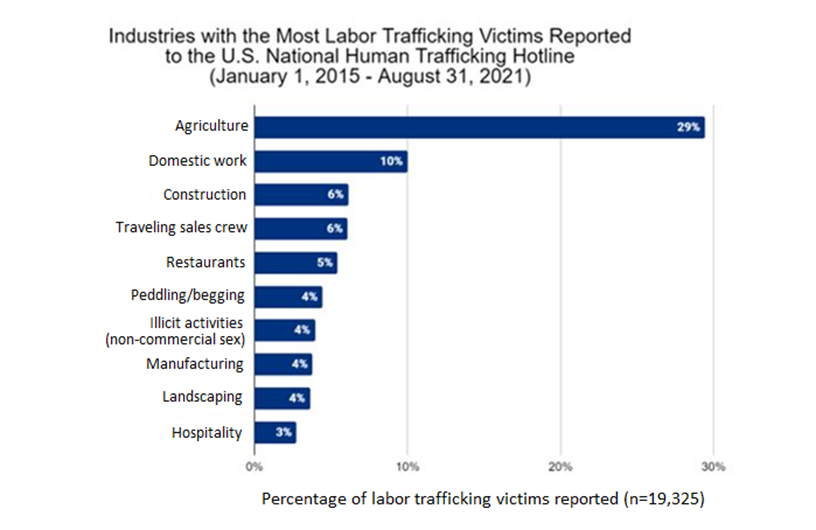

In the U.S., high-risk industries for labor trafficking include agriculture, landscaping, hospitality and non-unionized segments of the construction industry (see Figure 4).4

Figure 4: Industries With the Most Labor Trafficking Victims

Source: Data from the National Human Trafficking Hotline Operated by Polaris

Defining the Indicators

Efforts to implement traditional rules-based transaction monitoring to detect—proactively and/or reactively—situations of forced labor, often prove challenging. However, FIs can utilize several methods and indicators to detect a subset of customers that may require additional review. For example, checking negative news and training account managers to detect clients in high-risk industries based on indicators of labor trafficking are two methods that anti-financial crime (AFC) professionals have implemented. In addition, sources such as the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)5 have identified general labor trafficking indicators of which AFC professionals should be aware.

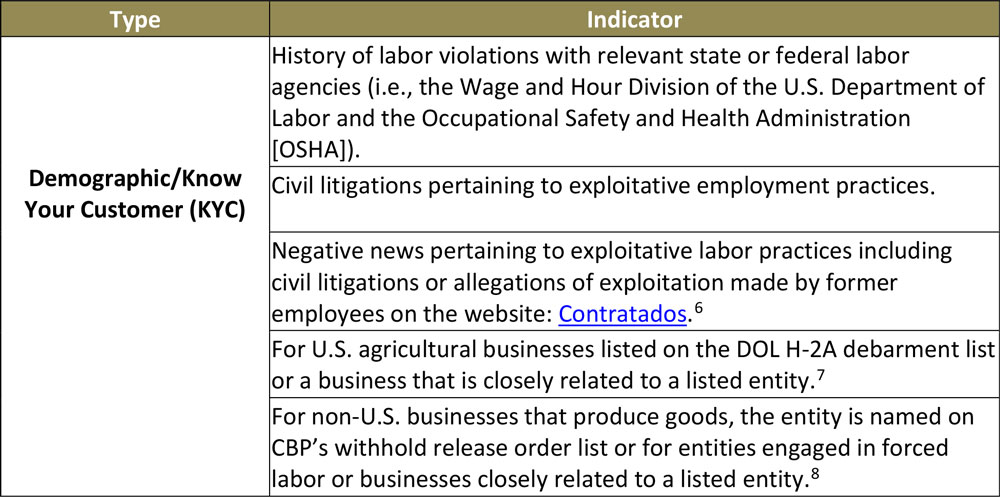

Non-Traditional Sources of Negative News

Rather than screening for negative news explicitly referencing labor trafficking, FIs can also screen adverse media pertaining to allegations of other forms of labor abuses. While these violations likely do not constitute forced labor by themselves, businesses that utilize forced labor have extensive histories of other exploitative practices. The indicators in Table 2 reference sources of information that are often not included in traditional negative news screenings but may be particularly useful in identifying customers at a high risk of labor trafficking.

Table 2: Indicators of Exploitative Practices

Partnership with Account Managers in Relevant Lines of Business

Once properly trained on labor trafficking, account managers can be key partners in identifying accounts for further review due to their relationships with their customers and their knowledge of normal business practices within particular industries. Account managers play a critical role in collecting information during the account opening process and are well-positioned to flag discrepancies or abnormalities in customer behavior. Finally, account managers can request additional information from customers when a concern has been identified.

Labor Trafficking Indicators

AFC investigators should consider the following red-flag indicators of labor trafficking, particularly if adverse media pertaining to exploitive labor practices has already been identified or if a concern has been flagged by the line of business.

Table 3: Indicators of Labor Trafficking

Conclusion

In this series of articles, we have begun to explore the complex dynamics associated with HT. A diverse crime, HT is often perpetrated through complex psychological manipulations or the exploitation of economic desperation or emotional need. But behind all the complexity, the main motivation of traffickers is simple: money. Accordingly, AFC professionals have a uniquely critical role in the fight against human traffickers. Together, we can identify trafficking operations through their financial footprints, support criminal cases that mitigate the burden placed on victims to participate and facilitate the financial restitution process—ultimately decreasing the profitability of trafficking while increasing accountability for the traffickers.

Sara Crowe, strategic initiatives director, Financial Systems Polaris, Washington, DC, LinkedIn

Chris Bagnall, CAMS-FCI, CFE, LinkedIn

- Chris Bagnall and Sara Crowe, “Understanding Human Trafficking,” ACAMS Today, April 19, 2022, https://www.acamstoday.org/understanding-human-trafficking/

- “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage,” International Labour Office, Walk Free Foundation, International Organization for Migration, 2017, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---ipec/documents/publication/wcms_586127.pdf

- Andrew Crane, “Modern Slavery as a Management Practice: Exploring the Conditions and Capabilities for Human Exploitation,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 38, No. 1, p. 45–69, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23416302

- For more data from the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline, visit https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states

- “Following the Money: Compendium of Resources and Step-by-step Guide to Financial Investigations Into Trafficking in Human Beings,” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, November 7, 2019, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/438323

- Contratados, https://contratados.org/en

- “Wage and Hour Division Debarments Barring Participation in OFLC Programs,”U.S. Department of Labor,https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/oflc/pdfs/Debarment_List.pdf

- “Withhold Release Orders and Findings List,”U.S. Customs and Border Protection, https://www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings