This article is the second of a three-part series on human trafficking.

As we learned in the article Understanding Human Trafficking, in the U.S., sex trafficking is defined as follows:

“The recruitment, harboring, transportation, obtaining, patronizing, soliciting, or advertising of a person for a commercial sex act in which the commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age.”

But what does this really look like in real life? How would an anti-financial crime (AFC) professional at a financial institution (FI) detect it? And what are the special dynamics associated with sex trafficking that AFC professionals need to consider?

Diverse Sex Trafficking Business Models and Financial Typologies

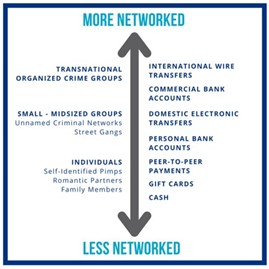

Contrary to what Hollywood would have you believe, not all sex trafficking situations involve highly networked and sophisticated international organized crime (IOC) syndicates. While transnational organized crime groups do engage in sex trafficking, many sex trafficking situations involve non-networked traffickers. In fact, sex trafficking is often perpetrated by a single individual. This individual is often a romantic partner or a family member of the victim(s).

Depending on the business model and the extent to which the trafficker(s) are networked, the financial typologies of sex trafficking situations can vary considerably. The types of financial services and products misused by traffickers will also differ based on these factors. For instance, an IOC group engaged in sex trafficking in the U.S. may be highly motivated to move its profits internationally and therefore utilize international wire transfers. A U.S. based individual trafficker would have no need to make an international transfer and thus, may more heavily utilize peer-to-peer payment platforms that are only operational in the U.S. (see Figure 2).

This article reviews two of the most commonly used business models by sex traffickers in the U.S. The first model is commercial-front brothels and the second model is in-call/out-call escort services. While much of this information is based on the U.S., these business models are commonly found outside of the U.S. and many of the associated financial indicators remain consistent across geographies.

Commercial-Front Brothels

Sex trafficking often occurs at businesses that are legally registered entities outwardly claiming to provide legitimate services, but function primarily as brothels, known as “commercial front brothels.” Though these businesses can have varied fronts, the industries most associated with commercial-front brothels include massage or spa services, hostess or strip clubs and bars or restaurants.1 In some instances, the business provides a combination of legitimate and illicit services while in others, the business overwhelmingly provides illicit sexual services. Commercial-front brothels may be operated by small, mid-sized, or expansive organized crime groups (see Table 1).

| Indicator Type | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Demographic/KYC | Advertisements associated with the business are overtly sexualized (i.e., include images of women in lingerie). |

| Demographic/KYC | Business is referenced on a sex-buyer review board with multiple users alleging they have received commercial services at the establishment. |

| Demographic/KYC | Adverse/negative news flags which link the business or a business owner, manager, or registered agent to prostitution. |

| Transactional | Transactions with commercial sex advertising (CSA) sites. |

| Transactional | High volume of business transactions occurring during off peak times, overnight, or outside of business hours. |

| Transactional | Business accounts reflect abnormal payroll expenditures such as non-existent or extremely low payroll costs incommensurate with other similar businesses or payroll is processed very infrequently (i.e., every few months). |

| Transactional | Beauty service business with high frequency and volume of transactions on credit cards registered to men (or names of card holders are primarily identified as male in the event gender-specific information is not recorded). |

| Transactional | High frequency of transactions with drug stores, women's clothing stores, beauty supply or services that are incommensurate with normal spending habits. Risk is elevated if transactions are with lingerie companies, sex toy companies, or wholesale condom distributors. |

In-Call/Out-Call Escort Services

In the in-call/out-call escort service business model, sexual services are typically advertised online and then the commercial sex occurs at a residence or hotel/motel owned or rented by the commercial sex provider (known as “in-call” services) or by the commercial sex buyer (known as “out-call” services).2 In many situations, a combination of in-call and out-call services are provided. Previously, advertising largely occurred on websites specifically created for this purpose (known as commercial sex advertising or “CSA” sites). While CSA sites continue to exist and are regularly used, advertising for in-call/out-call commercial sex services in the U.S. is increasingly done through other online platforms such as mainstream social media apps, dating apps, and through webcamming platforms. Though organized networks do exist, sex traffickers using the in-call/out-call model are often less networked than those operating commercial sex brothels (see Table 2).

| Indicator Type | Indicator |

|---|---|

| KYC/Demographic | Unusual number of unrelated individuals listed as joint account holders, or authorized users of products such as credit cards. |

| Transactional | Transactions with commercial sex advertising (CSA) sites. |

| Transactional | Unusual cash deposit patterns including:

Cash deposits outside the account holder's reported state of residency, high number of cash deposits made at night. |

| Transactional | High frequency of transportation/hospitality charges that are incommensurate with the customer’s personal use or stated business. This activity may include:

Variation: Frequent credit card authorizations at hotels, room service charges, or other transactions at hotels or hotel-casinos but no subsequent room charge |

| Transactional | High volume of ride-share charges. Risk is elevated if ride-share charges occur after midnight or charges suggest a pattern of paying for multiple ride-share trips in close succession or simultaneously. |

Special Considerations Regarding Sex Trafficking

Regardless of the business model they use, sex trafficking is a complicated crime, often perpetrated through complex psychological manipulations and the exploitation of economic desperation. AFC professionals should remain cognizant of these dynamics—particularly when attempting to differentiate between consensual and nonsexual commercial sex activity and when distinguishing between victims and perpetrators.

Consensual Activity vs. Sex Trafficking

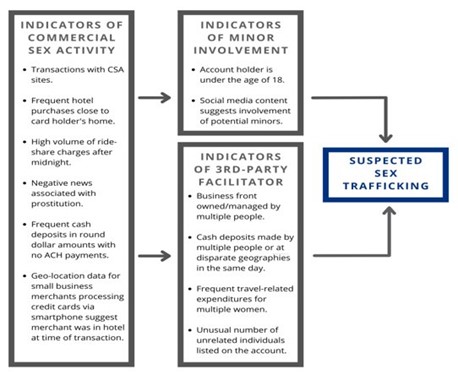

Not all adults providing commercial sexual services are victims of sex trafficking. There are a variety of reasons that a person may engage in such activity without being forced, defrauded or coerced into this act. Additionally, because sex trafficking victims are often coached to hide indicators of their victimization, it can be very difficult to differentiate between situations of sex trafficking and situations in which an adult is independently engaging in this activity. From the vantage point of an AFC professional, it may not always be possible to determine whether or not suspected commercial sex activity is related to sex trafficking, but AFC professionals can attempt to do so by 1) reviewing for any evidence of the involvement of minors in the activity, and 2) looking for indicators which suggest the involvement of a third-party facilitator.

Involvement of a Minor

As discussed in our previous article, under U.S. law (and the law of most jurisdictions), individuals under the age of 18 are too young to consent to participation in commercial sex. As such, any minor engaged in commercial sex is automatically considered a victim of sex trafficking. Any suggestion of a minor’s involvement in commercial sex should be flagged as potential trafficking by AFC professionals. Though relatively rare, suspicious activity may be identified on an account registered to a minor. In other instances, social media content may suggest the involvement of minors.

Involvement of a Third-Party Facilitator

While not definitive, information which suggests the involvement of a third-party facilitator significantly raises the likelihood of sex trafficking. Indicators which signal a third-party’s involvement are often based on high-frequency or high-value transactions (as compared to other transactions of the same type), which might suggest a single person is obtaining goods or services for multiple people. Other indicators of the presence of a third party involve (offline) activity in multiple geographies around the same time—again, suggesting the involvement of multiple people (see Figure 3).

Victim vs. Perpetrator

Unlike other crimes, it can be difficult to ascertain whether an account holder suspected of involvement with sex trafficking is a victim or a perpetrator because of the frequent use of victims’ identities and accounts for money laundering purposes. The Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE) analyzed financial indicators of trafficking published by 23 different sources and noted that “the majority of indicators identified are derived from [trafficking] victim’s bank account records while under control of their trafficker.”3 This sentiment is confirmed by survivor experts. In a small-scale survey of survivors of trafficking in the U.S. conducted by Polaris in 2017, 26% of respondents reported that their trafficker(s) had used their account(s).4

Financial institutions should be cognizant of this trend and attempt to differentiate suspected victims from suspected perpetrators whenever possible. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) advises that in situations in which the accountholder is suspected to be a potential victim of human trafficking, this individual should not be reported as the subject of the SAR. Instead, all information pertaining to the victim would be included in the SAR narrative.5 De-risking should be considered a last resort and based on “heightened concerns above general suspicion.”6 Efforts should be made to coordinate with law enforcement and comply with requests to maintain accounts under investigation in order to avoid compromising an ongoing investigation.7 Financial institutions can also consider participating in financial inclusion initiatives for trafficking survivors and other underbanked communities vulnerable to trafficking.8

Conclusion

As described in the first article, sex trafficking is one part of the U.S. federal definition of human trafficking. In our next article we will tackle the second part of this definition, labor trafficking, which is believed to be more prevalent than sex trafficking but much more rarely identified.

Sara Crowe, strategic initiatives director, Financial Systems Polaris, Washington, DC, LinkedIn

Chris Bagnall, CAMS-FCI, CFE, LinkedIn

- For a commercial-front brothel-based sex trafficking case study, see the Hortencia Medeles-Arguello aka “Tencha” case in the ACAMS certification course: “Fighting Modern Slavery & Human Trafficking Part 2: U.S. Sex & Exploitation Cases,” ACAMS, https://www.acams.org/en/training/certificates/fighting-modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking-part-2

- For a commercial-front brothel-based sex trafficking case study, see the James Vernon Joseph Jr. aka “Spyder” case in the ACAMS certification course: “Fighting Modern Slavery & Human Trafficking Part 2: U.S. Sex and Exploitation Cases,” ACAMS, https://www.acams.org/en/training/certificates/fighting-modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking-part-2

- “Following the Money: Compendium of Resources and Step-by-step Guide to Financial Investigations Into Trafficking in Human Beings,” OSCE, November 7, 2019, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/438323.

- “On-Ramps, Intersections, and Exit Routes: Financial Services Industry,” Polaris, July 2018, https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/A-Roadmap-for-Systems-and-Industries-to-Prevent-and-Disrupt-Human-Trafficking-Financial-Industry.pdf

- “Supplemental Advisory on Identifying and Reporting Human Trafficking and Related Activity,” FinCEN, 15 October, 2020, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/advisory/2020-10-15/Advisory%20Human%20Trafficking%20508%20FINAL_0.pdf

- Following the Money: Compendium of Resources and Step-by-step Guide to Financial Investigations Into Trafficking in Human Beings,” OSCE, November 7, 2019 https://www.osce.org/secretariat/438323

- “Requests by Law Enforcement for Financial Institutions to Maintain Accounts,” FinCEN, June 13, 2007 https://www.fincen.gov/index.php/resources/statutes-regulations/guidance/requests-law-enforcement-financial-institutions-maintain

- Example initiatives include: “Survivor Inclusion Initiative,” Liechtenstein Initiative, https://www.fastinitiative.org/implementation/survivor-inclusion/;

Freefrom.org, https://www.freefrom.org/