Monetary value has taken various forms over time—beef, salt, mother of pearl, amber, metal, paper, shells, etc. Today, there are two types of money issued by countries via their central banks: fiduciary money or fiat (money and banknotes) and scriptural money (checks and transfers). But private players are competing with these currencies and offering the so-called ‘electronic’ or ‘decentralised cryptocurrencies’, which issue peer-to-peer digital assets without the need for a central bank because they can be used through a decentralised computer network. There are more than a hundred cryptocurrencies, but the most famous are bitcoin, ethereum and ripple. Although they guarantee effective decentralisation and complete independence from any monetary authority, these assets suffer, among other things, from high volatility. So much so that these private digital currencies could undermine the ability of central banks to control inflation and provide loans of last resort, as their monetary policy tools—overnight rates and lending mechanisms—only work with the currency they issue.

To this end and to preserve their national sovereignty, countries have taken the plunge and started to develop their own central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which can be defined as a digital form of fiduciary currency (euro, dollar, yuan, etc.). These are issued, controlled and regulated by the central bank of a country or a monetary zone. A CBDC has the same functions as a traditional currency: A means of payment, a store of value and a unit of account. Considered by Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, as one of the ‘most important innovations in history’,1 it would be a virtual representation of the fiduciary currency without some of its characteristics, notably anonymity.

CBDCs Around the World

To prevail, launching CBDCs around the world will have to respond to the fierce competition between cryptocurrencies and also between countries and will have other factors to take into account in an ever-changing world.

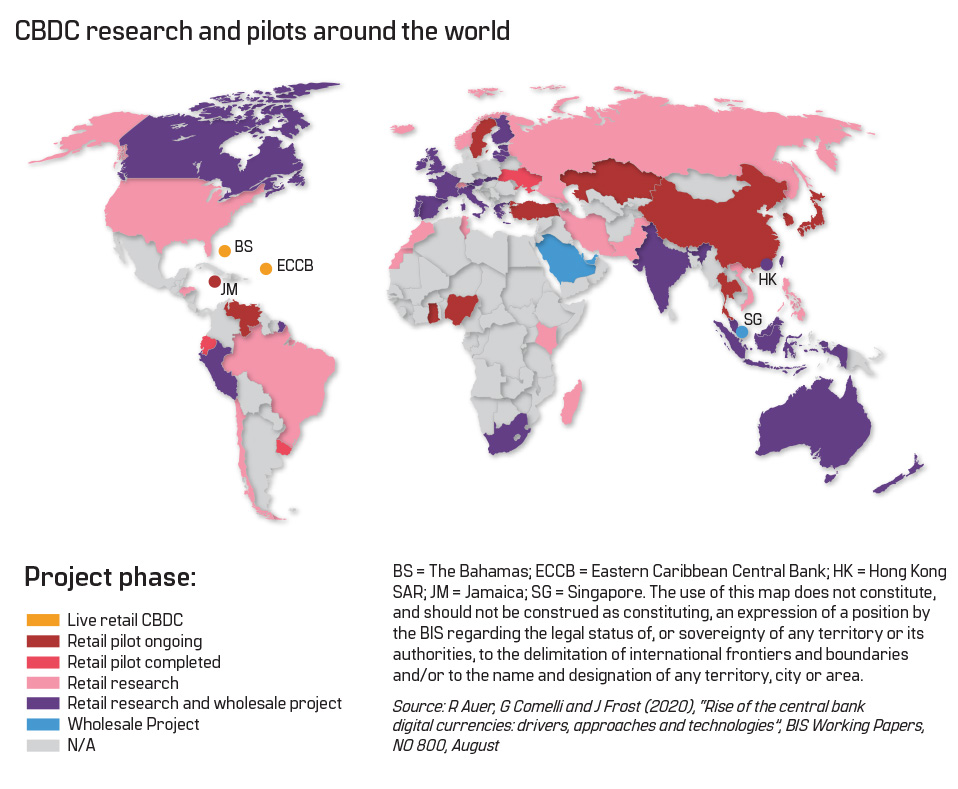

The map below tracks the status of CBDC projects being explored around the world, including those that have already launched a CBDC.

The primary quality of CBDCs to be perennial is to address the failures of private digital currencies. Thus, stability must be set up as a cardinal point, and only a well-defined regulatory framework will allow it to be established in the long term. The finance ministers and central banks of the Group of Seven (G7) member states defined guidelines for this purpose on 13 October 2021.2 China, a leader in CBDCs, had already proposed global rules for CBDCs in March 2021.3

Although not binding, they can serve as a reference for future national, European or international legislation. It is also clear that CBDCs should in no way undermine the monetary and financial stability of their market but rather support this capacity and evolve as a complement to cash. They could also serve as a liquid and secure payment asset and anchor for payment systems.

The Challenges

The danger posed by CBDCs is that countries subjectively envision their CBDCs and base their infrastructure on individual technological and security systems that suit them. For example, the tragic-comic management of taxes on digital services—known as the Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon (GAFAM) tax—pleases France but not Ireland. Indeed, Ireland has been the low-tax European headquarters for tech giants, and it took several years of negotiations for Ireland to agree to harmonise its tax rate on GAFAMs, going from 12.5% to 15%.4 This example shows the abysmal differences in points of view and the difficulties countries have in reaching an agreement on this type of issue. Nor should it be anti-competitive. Otherwise, countries will deviate from the rules to adapt to this market, or the less regulated countries will get ahead (and even win the CBDC race).

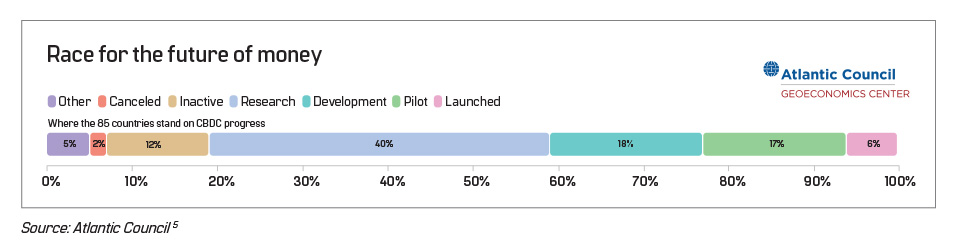

The graph below shows the percentage in completing the race for the future of money among 83 countries across the globe.

CBDCs will need to demonstrate interoperability across different markets to help improve cross-border payments and enable greater financial inclusion. Indeed, central banks are keen to ensure that any transition to digital currencies includes improving access for unbanked customers. This is a major issue, considering that worldwide, 1.7 billion people did not have a bank account in 2018.6 A CBDC must work for banks, certainly not against them or without them. Because in addition to mastering know your customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) processes, putting CBDCs to compete with BigTechs would be their downfall. These private companies have unparalleled resources and network effects and will undoubtedly succeed in developing a stable coin, a digital asset that replicates the face value of a fiat currency, often the dollar. In response, the G7 stated that “no global stable coin project should begin operations until it meets regulatory and oversight requirements.”7 In particular, these requirements have slowed the rollout of the Novi, formerly known as the Calibra project, Facebook’s interoperable digital wallet dedicated to Diem (formerly referred to as Libra), the stable cryptocurrency initiated by the social network but later relegated to the nonprofit consortium of the same name.

Regulation

Money is a public good to which equal access is a human right

Digital currencies must meet rigorous privacy standards. Thus, the CBDC market should be placed at the same level as the other traditional financial services, and the same forms of protection should be guaranteed to investors and users. These include the disclosure of certain key information, available at any time to anyone wishing to invest, and a guaranteed right to withdraw. CBDCs will need to be transparent about how data may be used and stored. The stakes are high and must be guaranteed by the state, which cannot and must not have any possibility of interfering in the private lives of individuals by controlling how they save, send, spend and secure their money. Money is a public good to which equal access is a human right.

A Centralised Economy

CBDCs will be mandatorily centralised, which would not only make them highly vulnerable to cyberattacks but would increase the surface area and attack vectors to now include central banks, among others. The magnitude of such a risk can be measured by the cyberattack on Equifax in 2017, involving 143 million personal identification records representing almost the entire US workforce.8 Or more recently, with the case of SolarWinds, whose cyberattack spread to its customers and went undetected for months. This allowed hackers to spy on private companies like the elite cybersecurity firm FireEye and the upper echelons of the US government, including the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of the Treasury.9 Thus, the solution would be to host CBDCs on a public blockchain, as well as a competitive free market so that the movement of value on the internet is a better long-term posture. The trust that customers will place in CBDCs is at stake, and just as the failure of a bank erodes confidence in the banking sector, central banks could lose their credibility, a real asset, on stable coins and other cryptocurrencies. The European Commission has understood this challenge and has published the draft regulation called the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which aims to improve the information technology (IT) operational resilience of financial services players by implementing specific governance and internal control framework (information and communications technology, or technologies [ICT] risk management framework).10

CBDCs must also take a stand in the fight against illicit financial flows. With limited traceability, cryptocurrencies can be used to illicitly move money or capital from one country to another. Thus, a balance must be struck between the complete anonymity and the privacy of users that may facilitate illegal activities and perfect traceability that would hinder the interest of CBDCs of users who will not wish to record part of their transactions. It is important to note that the People’s Bank of China has introduced, in addition to the digital yuan, a payment infrastructure that would bypass the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, which plays a key role in US sanctions and monitoring of illicit financial flows.11 Having another global interbank messaging system will make monitoring and globalising the fight against illicit financial flows even more complex.

Finally, the issue of energy efficiency must also be considered in the development of CBDCs. Mining to extract a cryptocurrency coin and maintaining the blockchain on which it resides consumes as much energy as a country like Argentina consumes in a year.12 Elon Musk said that his company, Tesla, would take over bitcoin transactions on the condition that miners prove that they use clean energy reasonably.13 On the contrary, CBDC has the advantage that it does not need to be mined. In fact, bitcoin miners must show proof of work to earn their new coin, whereas a CBDC can be created with the click of a mouse. This is confirmed by the experiments by China with the digital yuan, which did not involve energy-intensive mining, in comparison to the creation of new bitcoins.14

Conclusion

CBDCs provide an opportunity to ‘set a benchmark’ for how future payment and settlement systems will be designed for ‘optimal energy efficiency.’15

Whilst the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (including countries such as the US, Canada, Japan, UK and others) and the European Central Bank have not yet decided whether the CBDC project will succeed. China has already implemented its digital yuan in some cities and declared all cryptocurrency transactions illegal.16 If states do not want to be left behind and impose a CBDC system that does not suit their value, international cooperation will have to be established.

Xavier Aubert, KYC analyst, Alcyone consulting, xavieraubert11@gmail.com

- “Une cryptomonnaie de banque centrale serait une des ‘innovations les plus importantes de l‘Histoire’, pour la Banque d’Angleterre,“ Capital, 11 June 2021, https://www.capital.fr/entreprises-marches/une-cryptomonnaie-de-banque-centrale-serait-une-des-innovations-les-plus-importantes-de-lhistoire-pour-la-banque-dangleterre-1406190

- Raphael Auer, Giulio Cornelli and Jon Frost, “Rise of the central bank digital currencies: drivers, approaches and technologies,” Bank for International Settlements, 24 August 2020, https://www.bis.org/publ/work880.htm

- “G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Statement on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) and Digital Payments,“ UK Government, 13 October 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1025234/FINAL_G7_Statement_on_Digital_Payments_13.10.21.pdf

- Tom Wilson and Marc Jones, “China proposes global rules for central bank digital currencies,“ Reuters, 25 March 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/china-proposes-global-rules-central-bank-digital-currencies-2021-03-25/

- Georgi Gotev, “Ireland agrees to global tax deal, sacrificing prized low rate” Euractiv, 8 October 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/news/ireland-agrees-to-global-tax-deal-sacrificing-prized-low-rate/

- Julia Friedlander, “The Promises and Perils of Central Bank Digital Currencies,” Atlantic Council, 27 July 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/testimony/friedlander-testifies-to-house-committee-on-financial-services-regarding-us-leadership-for-central-bank-digital-currency-development/

- Clémentine Maligorne, “Près de 4 adultes sur 10 dans le monde ne possèdent pas de compte bancaire,“ Le Figaro, 19 April 2018, https://www.lefigaro.fr/conjoncture/2018/04/19/20002-20180419ARTFIG00196-pres-de-4-adultes-sur-10-dans-le-monde-ne-possedent-pas-de-compte-bancaire.php

- Rafael Miró, “Les stablecoins, ces cryptomonnaies immobiles,“ LaPresse, 2 July 2021, https://www.lapresse.ca/affaires/2021-07-02/les-stablecoins-ces-cryptomonnaies-immobiles.php

- Tara Siegel Bernard, Tiffany Hsu, Nicole Perlroth and Ron Lieber, “Equifax Says Cyberattack May Have Affected 143 Million in the U.S.,“ New York Times, 7 September 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/business/equifax-cyberattack.html

- Isabella Jibilian and Katie Canales, “The US is readying sanctions against Russia over the SolarWinds cyber attack. Here‘s a simple explanation of how the massive hack happened and why it‘s such a big deal,“ USA TODAY, 15 April 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/solarwinds-hack-explained-government-agencies-cyber-security-2020-12?r=US&IR=T

- “ISACA Provides Guidance Around EU’s Proposed Digital Operational Resilience Act,“ ISACA, 14 October 2021, https://www.isaca.org/why-isaca/about-us/newsroom/press-releases/2021/isaca-provides-guidance-around-eu-proposed-digital-operational-resilience-act

- Rajesh Bansal and Somya Singh, “China’s Digital Yuan: An Alternative to the Dollar-Dominated Financial System,“ Carnegie India, 31 August 2021, https://carnegieindia.org/2021/08/31/china-s-digital-yuan-alternative-to-dollar-dominated-financial-system-pub-85203

- Cristina Criddle, “Bitcoin consumes ‚more electricity than Argentina’,“ BBC, 10 February 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-56012952

- Emma Newburger, “Musk says Tesla will accept bitcoin again as crypto miners use more clean energy,“ CNBC, 13 June 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/13/musk-tesla-will-accept-bitcoin-when-miners-use-clean-energy.html

- Arjun Kharpal, “A major Chinese bitcoin mining hub is shutting down its cryptocurrency operations,“ CNBC, 2 March 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/02/china-bitcoin-mining-hub-to-shut-down-cryptocurrency-projects.html

- “Public Policy Principles for Retail Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs),“ G7 United Kingdom 2021, https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/international_policy/convention/g7/g7_20211013_2.pdf

- “China declares all crypto-currency transactions illegal,“ BBC, 24 September 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-58678907#:~:text=China‘s%20central%20bank%20has%20announced,the%20safety%20of%20people‘s%20assets%22